Consumer safety experts want to make buying bike kit online safer

A new law could finally force online giants like Amazon, eBay, and Temu to take responsibility for the flood of unsafe motorcycle gear sold through their platforms.

Bargain-basement lids and fake CE labels are flooding the market thanks to online only sellers, but a new law could finally force online giants to play by the same safety rules as your local bike shop.

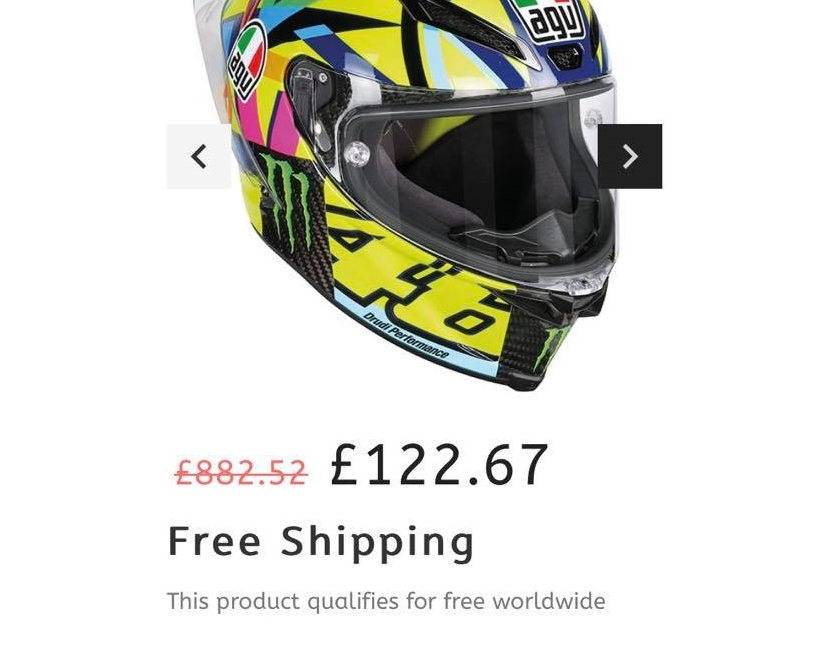

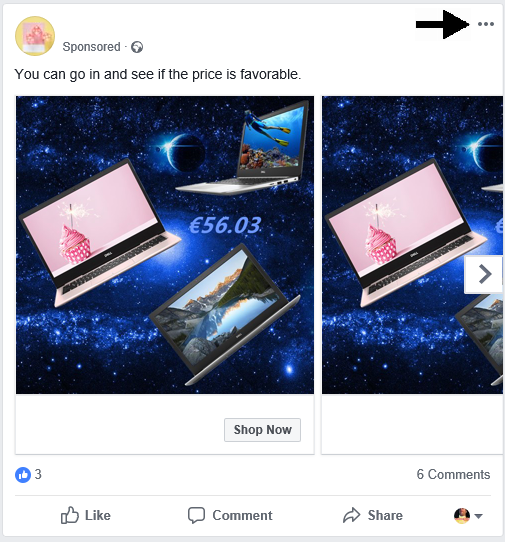

If you’ve ever scrolled through Amazon, eBay or Temu and been tempted by a helmet for less than the cost of a pizza, you’ll already know the problem. They look the part, glossy carbon-effect shells, a few “CE” logos slapped on, maybe even some glowing reviews. But scratch the surface and it becomes clear: much of this stuff is about as protective as a plastic salad bowl.

It’s a situation that we highlighted not long ago, when the online retailer, Bikers Lifestyle, was forced to remove a huge amount of stock from its website due to it being uncertified and potentially very dangerous.

Now, finally, the government might be about to do something about it.

Earlier this month, the British Safety Industry Federation (BSIF), the consumer group Which? and a coalition that reads like the Yellow Pages of UK safety organisations, signed an open letter to Justin Madders MP, the Minister for Employment Rights, Competition and Markets. The message contained in the letter was clear: stop online marketplaces flogging unsafe products, and give brick-and-mortar shops a level playing field. It’s about protecting consumers from dodgy online sellers, but there is also a glimmer of light for the UK’s struggling high-street stores.

For motorcyclists, this matters more than most. While unsafe extension leads and knock-off toasters can be a headache, motorcycle kit and clothing can be the difference between life and death.

Let’s not sugar-coat it. Dodgy bike gear is everywhere online. Helmets that shatter in lab tests, gloves with fake EN certification, “armoured” jeans made of denim so thin you’d wear through them kneeling on your driveway.

Plenty of these products carry claims like “ECE 22.06 certified” or “CE-approved” when in reality they’ve never been near a test lab. Investigations by Which? and the BSIF have shown time and again that illegal and unsafe products are available to UK riders with nothing more than a few clicks. Even when listings are taken down, they often reappear under a different seller name within days, meaning the regulators are playing whack-a-mole with websites that in many cases originate from outside of EU and UK jurisdiction.

And while you or I might look at a £25 helmet and think, yeah, no chance, not everyone will. A new rider, perhaps on a tight budget, could be drawn in by the promise of “tested protection” at half the price of a recognised brand. The result? An entire corner of the internet filled with kit that looks protective but isn’t, eroding trust and putting lives at risk.

Bricks-and-mortar vs. the Wild West

Compare that to the rules a proper retailer has to follow. Walk into a local bike shop in Wolverhampton, Glasgow or Plymouth and every helmet, jacket and pair of gloves has to meet stringent safety standards. Trading standards officers can inspect the stock, and if something isn’t up to scratch, the shop is on the hook.

Online, it’s a different story. Marketplaces like Amazon, eBay, and Temu insist they’re “just platforms”, not sellers. That means the responsibility for safety supposedly rests with the thousands of third-party vendors, many based outside the UK, who use their storefronts. In practice? A revolving door of sellers with very little oversight.

It’s an uneven playing field. Legitimate shops invest in compliant products, certification, and aftercare. The other side of the market floods in with cheap, unsafe gear, undercutting them. The BSIF argues it’s not just dangerous, it’s unfair competition.

Enter the PRAM Act - and it’s not just about prams!

The Product Regulation and Metrology (PRAM) Act, passed in July 2025, is supposed to change that. At Royal Assent, ministers promised it would “hold online marketplaces to account for dangerous products sold through their platforms, creating a level playing field with bricks and mortar stores.”

For the first time, the Act gives the government powers to impose a duty of care on online marketplaces, making them legally responsible for what gets sold through their platforms. It also gives regulators the teeth to levy heavy fines or take enforcement action when platforms fall short.

But there’s a catch. The Act is a skeleton. The real bite comes from the secondary legislation, the detailed rules ministers are drafting right now. That’s why the BSIF, Which?, almost all UK Fire Brigades, Trading Standards, the Toy Association, and dozens of others have piled in with their open letter. They want to make sure the final rules aren’t watered down.

The open letter to Justin Madders MP pulls no punches. It argues that:

Online marketplaces must be accountable for every product sold, including preventing unsafe gear from being listed in the first place. It goes on to say that regulators must be empowered to hit platforms with heavy fines or tougher sanctions if they fail to comply.

Strong secondary regulations are the only way to stop unsafe products from flooding the UK market, ending what it calls the “absurd double standard” between online platforms and physical retailers.

In plain English: Amazon, eBay and co. shouldn’t be able to shrug and say, it is not their problem for much longer.

Why motorcyclists should care

_0.jpeg?width=1600)

The coalition backing this letter is broad, including everyone from Argos to Zurich Insurance. But if you’re a motorcyclist, the stakes feel especially high.

We already ride knowing the risks. That’s part of the deal. But when we buy protective kit, we’re relying on it doing what it says on the tin. A helmet should absorb impact. Gloves should resist abrasion. Armour should stay in place. These are the factors that prevent a low-speed slide down the high street from becoming months of rehab, surgery or even worse.

The surge of unsafe gear undermines that trust. Fake CE markings don’t just make it harder for consumers to know what’s legit; they actively endanger riders, all while driving proper shops out of business. If a local retailer is trying to sell you a £180 ECE 22.06-approved helmet, but Amazon is pumping out “similar” lids for £30, where does that leave them?

Over the years, several independent organisations and safety campaigners, including PVA-PPE’s Paul Varnsverry (whom Visordown often leans on for safety advice), have tested low-cost helmets and protective gear bought online. The results are sobering.

Helmets claiming to meet ECE standards split in half under impact, while supposed back protectors fold like cardboard under pressure. In one infamous case, a cheap “CE-approved” jacket offered less abrasion resistance than a supermarket hoodie.

The problem isn’t that affordable gear can’t be safe. Plenty of budget-friendly kit from established brands does a solid job. The problem is the flood of products pretending to be tested and certified when they’re not.

The PRAM Act is being hailed as a once-in-a-generation chance to modernise UK product safety laws for the digital age. The letter argues that without strong secondary regulations, we risk missing that chance entirely.

Because here’s the thing: enforcement only works if it has teeth. Dodgy listings reappear too quickly. Sellers vanish and rebrand overnight. Unless marketplaces themselves are forced to take responsibility, the cycle continues.

The letter doesn’t mince words:

“Only clear and strong requirements backed up by severe penalties will deter online marketplaces from allowing unsafe products to appear on their platforms in the first place.”

So, where does this leave us, the people out there actually riding?

For now, it means keeping your wits about you. Don’t assume that because something’s on a big-name platform, it’s legit. Check certifications carefully. Stick to trusted retailers where you can. Remember that if something looks too good to be true, like a “genuine” full-face lid for £20, it almost certainly is.

But looking ahead, if the BSIF and its allies get their way, the law could shift dramatically in riders’ favour. The hope is that in a few years’ time, the online Wild West of cheap, unsafe motorcycle kit will be a thing of the past.

Because when you’re sliding down the road on your elbows, or bouncing along the tarmac helmet-first, the last thing you want to wonder is whether the gear you bought actually does what it promised.

Motorcycling will always carry risk, that’s part of why we love it. But there’s a world of difference between the risk you choose to take, and the danger that’s dumped in your lap by shady sellers and lax regulations.

The PRAM Act is our chance to put that right. Now it’s down to the government to follow through, write tough rules, and make sure the next time a rider buys a helmet online, it protects them like it should.

Because at the end of the day, £19.99 lids might be tempting, but your head is worth more than a takeaway pizza.