Tracing the Crosstourer's V4 DNA

Part One: Ninety degree Vee

Honda have always had great faith in the V-4 layout and there’s no denying that it’s been responsible for powering some great bikes over the past three decades.

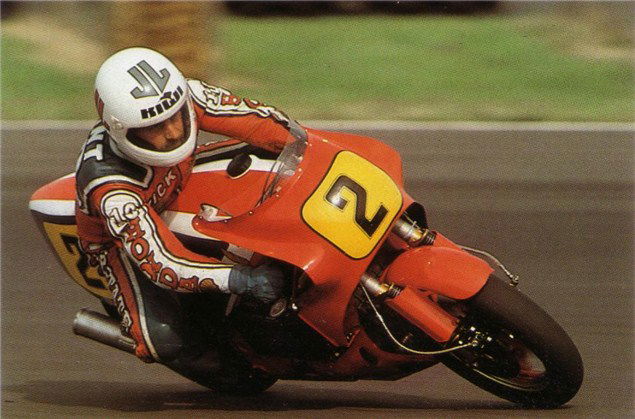

NR 'Never Ready' 500 race bike

Their first attempt at V-4 victory was possibly best forgotten for while the NR500 racer pushed the boundaries of four-stroke technology, its success on the track was limited, to say the least and non-existent to be totally frank.

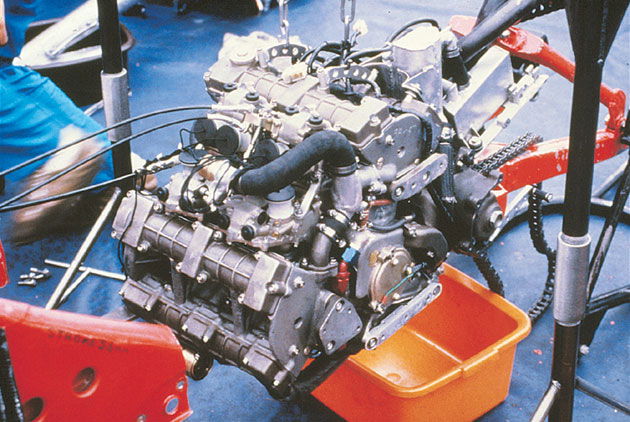

But, the NR500 wasn't a true V-4, it was actually a V-8 and a clever circumnavigation around the four-cylinder-only FIM GP rules. By using oval pistons (yes, really) Honda’s engineers effectively got two cylinders from one bore. So, in the respect it had four oval pistons arranged in a V, it was a V-4 but as each piston shared two combustion chambers, eight valves and two spark plugs, it was really a V-8. Clever... in principle.

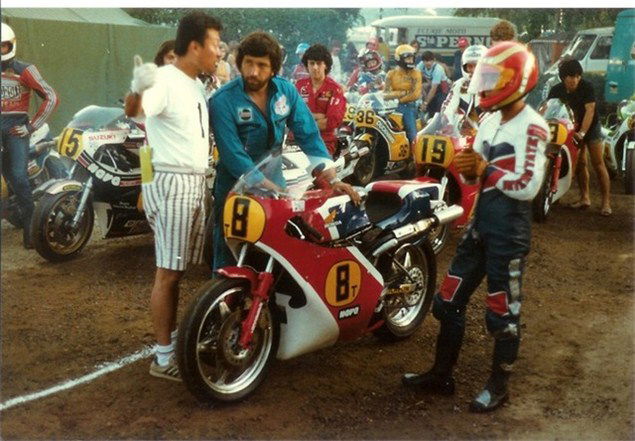

The NR (New Racing) project was driven by Soichiro Honda himself and started in 1977. The bike debuted at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone where riders Mick Grant and Takazumi Katayama both failed to finish. The NR’s best race result was 13th place, although Freddie Spencer did manage to get up to fifth place in the British GP of 1981 before retiring. It retired a lot.

Disaster or not, the NR500 paved the way for future Honda V-4s by pioneering new technologies and know-how.

Riding the NR500 by Mick Grant

‘The hierarchy at Honda decided they’d carry on where they left off in 1967. The poor buggers on the decks suddenly got handed a task that was never going to work. The most horsepower I had with that bike was 104bhp when a two year old RG500 Suzuki was putting out 118 on the same dyno. The factory two-strokes must have been putting out closer to 130bhp in that era.

The first year it wouldn’t tickover at less than 7,000rpm. Because of that, push starts were a bit of an issue to say the least. You were either going to start it off the line or you weren’t.

At Silverstone in 1979 at its first GP it fired on the third attempt with my legs like jelly. I went the full length of the pit straight on its back wheel. The piston rings wouldn’t seal properly so the crankcase pressure was enormous. The breather out of the engine and gearbox was always above the oil until you wheelied. Obviously it dumped all its oil over the back tyre and down I went at the first turn. The shortest race debut for any factory bike, I think.

The power started at about 12,500rpm and finished at 17,500. Although it’d rev to 22,500rpm, there was no point because it was all over by 17,500. But the worst thing about the NR was the lack of flywheel effect.

Going into Woodcote, for instance, it’d chatter the back wheel because there was no flywheel. I told the engineers we needed a clutch that slipped under reverse loadings which is, I guess, where the modern slipper clutch started. I thoroughly enjoyed the two years I had with them. There were some good guys in there. At that time they were bringing people through from other departments. That was great but we needed more experience, really. One bloke had spent three years designing the front fender on the Honda Accord.

Before I signed the contract with HRC I was told about all these radical ideas like ceramics and liquid nitrogen to cool it. I was excited. They left GP’s totally dominant and hearing all these fantastic ideas I had no reason to doubt they’d not be able to do it again.

I suppose the only way you know if you’re doing something right is to do it wrong first.’

The appeal of the V-4 for Honda was two fold. A 90 degree V produces perfect balance factors and its narrow width (compared to an in-line four) made packaging an easier task.

The early 1980s saw a raft of V-4 Hondas come and go, ranging from 400cc to 1000cc and until the arrival of the VF1000R, a race homologation special that used gear drive overhead camshafts, the overhead valve gear was driven by chain.

V-4 Warranty Claim

But the VF750 Interceptor changed all that. From new, this ground-breaking new sports bike was plagued with mechanical problems ranging from excessive camshaft wear to camchain tensioner problems – to name but two. The stricken VF750 nearly ruined Honda’s reputation forever.

In hind-sight we should be thankful.

Gear driven cams

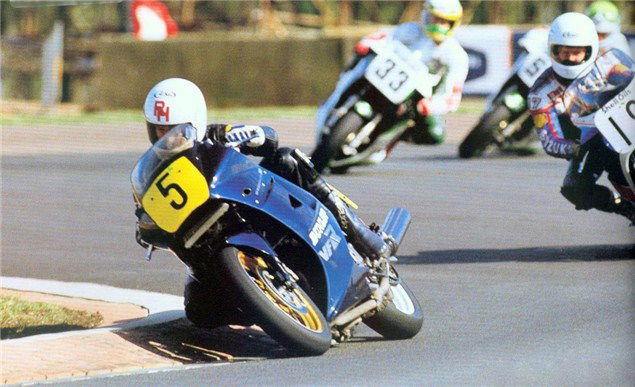

The barrage of warranty claims and damage to the Honda brand forced engineers to produce the VFR750 with its exquisite gear driven valve gear. In the UK the VFR750 made a historic debut at the Trans-Altantic Challenge races at Donington Park in 1986 with Ron Haslam at the controls. Haslam scored an amazing third place on a stock VFR750 in the pouring rain. There was even a tax disc on the inside of the fairing.

Allegedly Honda lost money on every VFR750 they made but it didn’t matter, there was a big reputation at stake that needed to be clawed back. Rather than call it a money loser, Honda used the phrase ‘in-built negative profit factor.’

It worked. With Haslam’s incredible race performance and rave press reviews, the VFR almost single-handedly salvaged Honda’s reputation around the World and the V-4 bed was made for the next three decades.

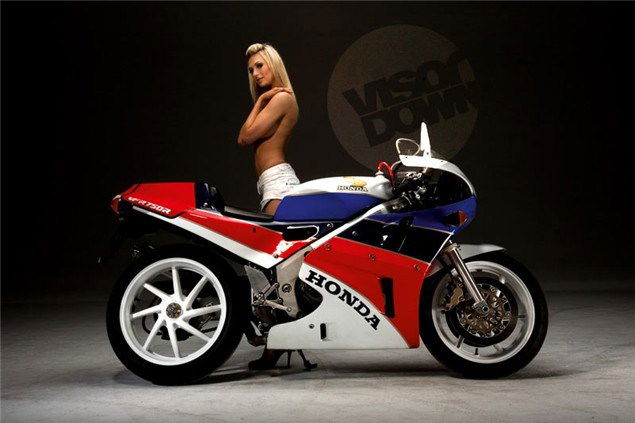

VFR750R RC30

The VFR paved the way for other great Honda V-4s. The legendary RC30 with its big-bang 360 degree crankshaft and it’s baby brother the NC30 made a huge impression on the track, the road circuits and the open roads as did its 750cc successor the RC45.

Their second-hand values today are testament to this greatness.

But the exotic VFR750R RC30 is something of a red herring in Honda’s V-4 story. The down-to-earth VFR road bike range is probably much more significant in terms of both volume and market impact.

War Horse

The VFR750 was a firm favourite but grew to the VFR800 in 1998. The controversial V-TEC model was introduced in 2001 and the re-adoption of chain-driven overhead camshafts came with it. Perhaps ahead of its time, the VFR800 has remained in the line-up ever since and now looks like a good fit among the swelling ranks of 800cc motorcycles like the FZ8, GSR750, Monster 796 - to name a few. The VFR800 still going a decade on? That’s some production run…