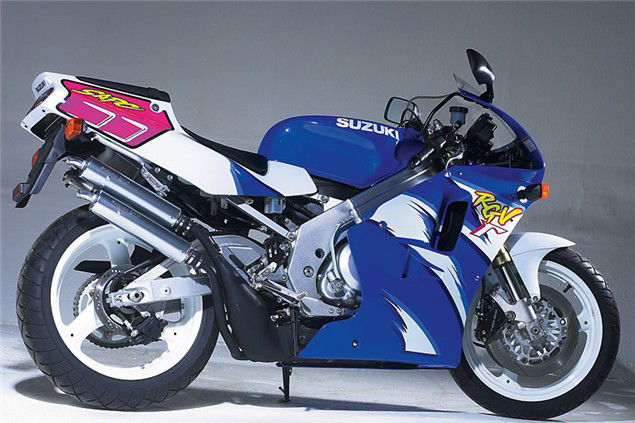

Bike Icon: Suzuki RGV250

1989 was a vintage year for hoodlum teenagers worldwide because this was the year Suzuki unleashed the RGV250, the purest and most race-bred two-stroke track tool ever to make it into a showroom

It was also one of the most accessible, as while the big four-stroke superbikes of the day like Yamaha's FZR1000 and Suzuki's own GSX-R1100 were well out of the financial clutches of all but the richest of youthful tearaways, the RGV was tantalisingly within reach. A bit of saving, a wallop of finance and any 19 year-old with a licence could buy (and more importantly, insure) a slice of the action.

He'd probably wrap that slice around a ditch within the week and then spend the next five years paying off the finance on a bike now irretrievably reduced to its component parts, but that's another matter, because as far as intense riding experiences go, the RGV was worth every penny.

Suzuki moved things on from their RG500 and RG250 to get the track look bang on.

For just over three grand you got the fattest aluminium beam frame yet seen on a production bike and a host of other pukka race-bred features like the underslung rear caliper and beefy race swingarm.

You also got sleek, crisp lines that mirrored Suzuki's GP bikes, a crackling V-twin two-stroke motor that stacked most of its 52bhp into a sky-high 2000rpm powerband and flighty precise handling to die for.

What you didn't get were creature comforts. The wafer thin seat was about as much fun as herpes, the pillion an insult to anyone outside of a pygmy tribe, and the mirrors showed your elbows but no more. Then there were the powervalves that had a habit of disintegrating within 10,000 miles and falling into the cylinders, destroying the motor, the lights that didn't really and the two-stroke fill-up that was impossible to use without pouring half a pint of the stuff over the back tyre.

None of this mattered though. In fact, it was all part of the RGV's appeal. It was a raw, harsh, impractical motorcycle that only made sense when ridden hard.

But with its bantam weight, outstanding handling (a decent RGV is still a defining sportsbike experience), firecracker motor and demon brakes the RGV could seriously deliver and introduced legions of otherwise unsuspecting riders to the joys of clutch slip, corner speed, knee-down and tankslappers.

Simply put, the RGV was nothing short of a revelation and a quantum leap forwards in performance and production bike technology.

There was competition of course. Yamaha's TZR250 was launched two years before, but simply didn't have the RGV's ultimate race feel. And in 1990, the KR-1S came out, which was faster, flightier and (unbelievably) less reliable.

Suddenly, the RGV had competition, but not for long, because in the same year Suzuki gave the bike a serious makeover. Fully-adjustable upside-down forks were slapped on, the carbs went up 2mm to 34mm for better midrange (even if 'more of not much' is still, erm, 'not much') and a gorgeous curved swingarm, just like the GP bikes. Jaws dropped, wallets opened, cash registers rung and the KR-1S never stood a chance.

This was the M model RGV, the one everybody wanted. It was just so damned horny. Who cared if the forks and swingarm had added another 10kgs to the dry weight? Or if the new carbs had slightly smoothed the all-or-nothing power delivery that had made the early models so explosive? This little 250 was the trickest thing on the road.

From here on the bike hardly changed. Graphics were updated year-on-year in an array of increasingly tasteless shell-suit options, and in 1992 the swingarm was braced, not curved, but factory interest was on the wane. Emissions laws would soon kill off the RGV and its smoky cohorts and by 1996 the party was over and RGV production ceased. Sure, in Japan there was an all-new RGV, but we never got to 'officially' taste it in the UK...

A parting word to the wise however. If this piece has you wetting your pants for an RGV, be very, very careful. Even new they were notoriously unreliable (10,000 miles without an engine rebuild was almost unheard of), many were raced, most were crashed, and the chances of them being owned by anyone possessing mechanical sympathy was next to nil. Cheap they may be now, but good ones are as rare as rocking horse shit. If you find one though, 'gis a bell...