No more heroes anymore

In this lilly-livered, cotton-wool, namby-pamby world we live in, the bike racing hard-man of the last century is a dying breed. Where have all the heroes gone?

The Bike Racing Hero is dead. Starved by the introduction of political correctness, injected with large doses of professionalism in the sport and brainwashed with an abject fear of telling the truth, he passed away some time in the early part of this century. This upsets me, as being a useless, good-for-nothing, overweight couch potato, for years I’ve lived life in the same way that many of us have – vicariously and through other people, normally through the medium of sport.

My sport isn’t football. Since the 1970s my Grandad has called them ‘poofters’. This isn’t a term to offend homosexuals today, and it wasn’t even because they had long unkempt hair like girls. He simply thought footballers were paid too much and did very little for it. So far as I can see, nothing in that sport has changed since Grandad’s time, apart from the haircuts. My sport is, and always has been, bike racing. Full of proper hard men, who rode through the pain barrier.

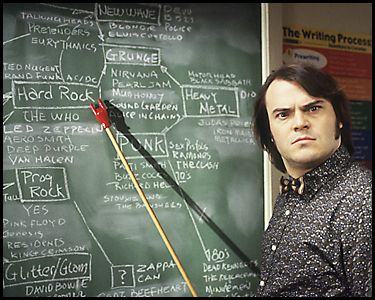

They entertained us, dancing on the twilight of adhesion one moment, battling a bastard of a bike to win the race or crash in the attempt, nursing wounds from last weekend before slugging from a bottle of champagne and tipping a wink to a topless glamour girl.

My heroes were people I wanted to be. I winced when they crashed, I screamed for joy when they won and insulted the opposition in the most xenophobic way imaginable when they got beaten (especially by Americans, the French or Germans.) Through them, I was truly alive, lifted from my near-comatose position on the sofa and transported to sit alongside them on the podium. And I thanked them for it.

But something’s changed. Today’s bike race stars are keener to set up their website than their suspension and they’ve degenerated into pre-programmed automatons, hair-gelled, homogenised homo-sapiens, no longer allowed to speak their mind or say their piece. Who killed The Bike Race Hero, and will we ever see his like again?

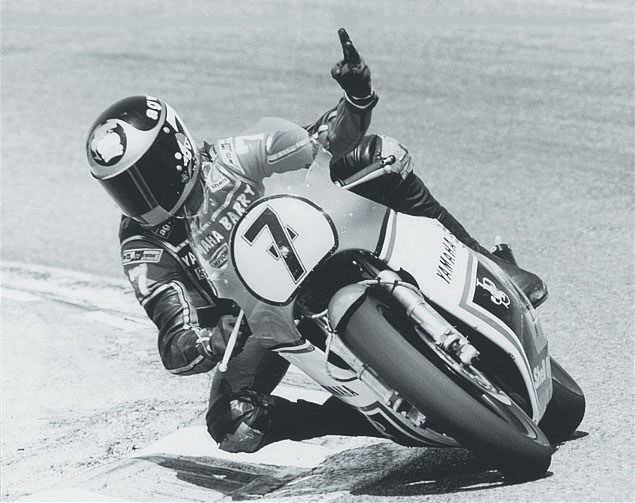

Flying over occupied France in a Lancaster Bomber during 1943 was something that could seriously curtail your life expectancy. Flight Lieutenant Robert Leslie Graham – pilot of a Lancaster bomber – had not only just taken part in a high-risk raid on vital U-boat pens in France, but had also stayed behind with his crew of seven to photograph the damage done by him and his fellow squadron mates despite attacking German fighters. ‘Les’ Graham received the Distinguished Flying Cross for valour and in 1949 he went on to become the first 500cc motorcycle World Champion. Obviously, he was British.

Mike Hailwood won the George Medal – the peacetime equivalent of the Victoria Cross – for rescuing fellow driver Clay Regazzoni from his flaming Formula One car in 1973. He also took victory in the 1965 TT, crossing the line on his battered MV Agusta with blood streaking his face following a crash after which he remounted to defeat Giacomo Agostini. Proper heroes, resolute, with a dash of bloody-mindedness.

Geoff Duke won the 500cc title four times and was World Champion six times. He used the kerbs and gutters at the Isle of Man TT to stop the rear of the bike sliding. On a Manx Norton, that takes balls. “In some ways it’s a much easier life for modern riders,” says Geoff today. “They only race in one class whereas riders used to race in as many as three Grands Prix in a day. It’s also more financially rewarding for today’s stars. But I can honestly say that I raced because I loved doing it, not because of what I was going to get paid. Money was secondary. The main consideration was the thrill, the challenge, and the competitiveness of the racing. Personally, looking from then to now, I get the impression that there are fewer personalities in the sport now.” My heroes don’t need to be larger or louder than life: Les Graham is remembered as a mentor and someone who was willing to offer advice to the young, up-coming stars of the day. Which fits the ID of some of my racing heroes such as Ron Haslam, Joey Dunlop and Niall Mackenzie.