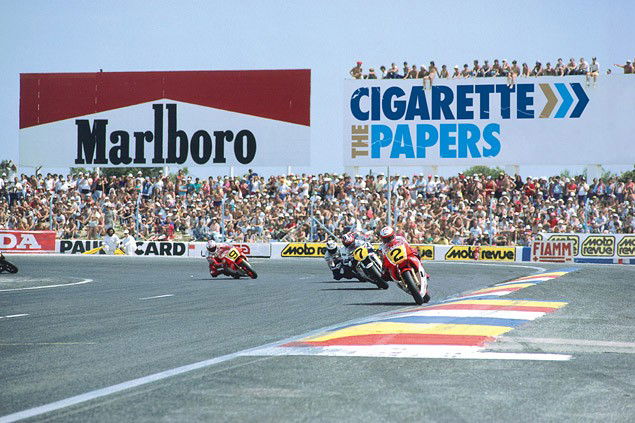

The Cigarette Papers: Grand Prix sponsorship

In the 1990s, cigarette sponsorship ran the world. Massive corporates, incredibly rich and powerful, went to war on the sidepanels and fairings of the fastest machines in the world. We remember a time when fag ash was king...

Cancer victim and timeless racing superstar Barry Sheene was the world’s greatest smoker. He even had a hole drilled in the chin-piece of his helmet so he could have a last few puffs on his Gitanes (the filter broken off) on the start-line. Sheene was also the unashamed pioneer of securing sponsorship money.

It is slightly surprising then that it wasn’t Barry who first pocketed the generous cash available from cigarette logos. That prize had already been taken by the time Sheene joined the 500 class in 1975, by illustrious incumbent Giacomo Agostini. Fifteen times world champ Ago raced in the twilight of his career with a small but highly significant logo on his fairing. It said: ‘Marlboro’.

The first appearance had been at the Isle of Man TT in 1972, with Ago and MV Agusta teammate Alberto Pagani. Present MotoGP race director Paul Butler remembers that the new sponsor took time to understand the ethos of bike racing. “They thought Douglas was somehow like Monaco, and they hosted a big party on a yacht in the harbour. They’d forgotten about the ten-foot tide, and the Manx Maid ferry coming in and out.”

Seasickness aside, the British-owned cowboy-boots brand was the first to join big-time bike racing, at a time when the whole concept of outside sponsorship was in its infancy. Thirty-six years later, cigarette advertising is banned almost everywhere except Qatar and Malaysia. But Marlboro alone is still there.

In between came the glory years, a cigarette war that escalated throughout the 1980s. Rothmans, Marlboro and Lucky Strike all tried to outdo and outspend the others. Off track, the hospitality suites burgeoned and the parties became more and more elaborate whenever there was anything to celebrate, and often when their wasn’t.

Bikes painted as fag packets dominated the grid, and the money flowed. Into the pockets of not only the top riders, but also a slew of ancillaries from technicians and team managers to a whole layer of free-spending PR schmoozers as well. The lunches were not only free but also very tasty. By the start of the 1980s, cigarette companies were already facing increasing restrictions on advertising, so they had to find another outlet for vast marketing budgets.

Car racing came first, and the bikes soon afterwards. And the money was like nothing anyone had ever seen. Informed speculation puts the fee paid to a top factory team like Yamaha at something like $15-million back in the early 1990s. Today, even with inflation, the same money would buy two or more years of the factory Honda or Yamaha teams, and a lot longer from Suzuki, rumoured to have accepted just half-a-million per annum from Rizla.

Unfiltered Tips

- Eight-times 500 champion Agostini was Marlboro’s first sponsored rider in 1972, and the lynchpin for securing Marlboro team sponsorship as Yamaha team manager in 1980.

- Kenny Roberts probably got more Marlboro money than anyone. A Marlboro rider in 1983, he took over the Marlboro-Yamaha team from 1987, then took the Marlboro Millions with him for two years when he started the ill-starred Modenas project in 1997.

- Gauloises came into GPs with Christian Sarron in 1979, but a French government ban ruled them out of bike racing in 1991. They came back in 2002, and won the title with Rossi in 2005.

- Rossi’s bid to escape cigarette sponsorship were unsuccessful after efforts to find backing for a one-rider team in ’05 and ’06 foundered. “I would rather race with tobacco sponsorship than not race,” he said.

- Rothmans came in big in 1985, the first sponsor for the factory Honda team. Freddie Spencer won both 250 and 500 titles; the Hondas stayed blue and white until 1991. Rothmans Hondas won again in 1987 (Gardner) and 1989 (Lawson). In 1994, they walked away to go F1 racing. Honda raced unsponsored that year.

- Marlboro’s first of four champions was Agostini on a Yamaha in 1975. Eddie Lawson won three of his four in Marlboro gear between 1984 and 1988; Wayne Rainey from 1990 to 1992. The next Marlboro winner was Stoner, in 2007.

- Lucky Strike came in one year after Rothmans, left for F1 in 1998 after the Suzuki results faded away. “They would think nothing of throwing a Schwantz championship party that cost more than a private team’s entire budget for the year,” said Suzuki team manager Garry Taylor.

When cigarettes ruled

As crucial was the influx of marketing expertise. Rothmans pioneered the use of on-bike cameras, for instance, and funded special TV shows for the then-new low-budget satellite and cable TV. Longtime Suzuki manager (and Lucky Strike beneficiary) Garry Taylor recalls: “The cigarette companies had the world’s top marketing people working for them. Not just one or two, in droves.” Butler added: “The big-time sponsors had the attitude that if you wanted results, then the budget to exploit the sponsorship must be double the sponsorship itself.”

Marlboro had led the way, and remained at the forefront throughout. Gauloises had also been early players, though on a smaller scale. By the mid 1980s, they had been joined by brand names both large and small.

Everyone will remember Rothmans, Lucky Strike and HB. Especially Rothmans, which joined the game at the very top in 1985, backing the factory Honda team and the shooting-star genius Freddie Spencer. He won both 500 and 250 titles that year. Rothmans also introduced a level of professionalism in presentation and exploitation that made even Marlboro’s efforts so far seem low-key.

Lucky Strike came in 1986, buying into Kenny Roberts’s Yamaha team, running as a rival to the central factory squad run by Agostini. One year later Roberts (with Wayne Rainey his key rider) had managed to secure the Marlboro Millions for himself...a habit in which the former triple champion persisted. Lucky Strike switched to Suzuki and Kevin Schwantz without even breaking stride.

There were other names which achieved only a fraction of the success of these big-timers. Local cigarette brands scrambled to get in on the act: Cabin and Mild Seven from Japan; Bastos, Fortuna, Ducados. Then came a second flush in the late ‘90s, with Gauloises returning and Camel coming along. The writing was on the wall, however. Impending legislation meant the spending would have to stop. This prompted both Rothmans and Lucky Strike to leave bike racing for a last fantastic spendathlon in F1.

Camel, Gauloises and Fortuna stayed on for the last hurrah – this much had been informally decided by the tobacco companies. In July 2005, a Europe wide ban on tobacco advertising came into effect; at the end of that year they would all pull out.

And they did. Well, almost all of them. Fortuna stayed for one last year with Lorenzo. And Marlboro just stayed. Even before the credit crunch struck, modern racing could only dream about the enthusiasm the tobacco sponsors had for spending money. We shall not see their profligate like again.