ABS - Is ABS the future for sports bikes?

In an industry first, Honda have produced a working prototype sportsbike ABS system that they hope will contribute to safer superbikes on the roads of Europe.

Bimota DB7 onboard at Tsukuba

-->

Combined braking systems. I’ll ‘fess up straight away: I don’t like them. The lever on the right bar is to apply front brakes, the pedal under your right toes is to apply the back brake- and there it should remain. I’ve been riding bikes since I was six and 33 years of ingrained practice have obviously left me prejudiced and resistant to change. My last experience with linked brakes involved a decreasing radius left-hander somewhere near Rhyader, a VFR800 and so much unintentional opposite lock I had to sit it up and take to an open-gated field. Bastard things. And then there’s ABS – fine in cars, don’t get me wrong – but bikes? Pants. Intrusive, crude and easily confused by irregular road surfaces. Early BMW sytsems were like operating a compressed-air powered road drill across an ice rink. Not pleasant.

But, and it’s a BUT the size of J-Lo’s, there are some grizzly things happening in the European motorcycle market at the moment. Check out a graph of European car road deaths and the gentle decline looks like a cross section of a ski-school nursery slope. Nice decreasing statistics that make the roads look like a very rosy place indeed.

Speak to anyone in the emergency services and they’ll also tell you like it is. There are less fatal accidents since the introduction of safety features. Jimmy Saville’s early clunk-click campaign coinciding with the seat belt law introduction made a stellar difference. Pre-tensioners, air bags, crumple zones, safety cells, head restraints, anti-lock brakes, electronic brake distribution, traction control, electronic stability – the car list of safety devices will continue to evolve and each step of that particular Darwinian ladder makes a massive difference to both accident avoidance and protection.

The bike graph isn’t quite so pretty. It’s a bit shit, actually. For starters it goes the wrong way – upwards at an angle that is the cause of concern for manufacturers, industry in general and close relatives. But the fact that we’re splatting ourselves with increasing monotony is starting to irritate the people who control and enforce legislation. And if there’s a group of people we can’t afford to piss off too much, it’s the Brussels policy makers. Full stop. So Honda are banging their safety drum, firstly because they can and secondly to be seen to be doing ‘something’ about this grim trend.

I’m assuming the last sentence, of course. However, during the lenghty Powerpoint session we endured before actually sampling Honda’s latest effort to stem the tide of draconian legislation, there were some token sound bites hinting at the problems facing us all. “We (motorcycling in general) will only have a bright future if we improve safety”, said a Honda spokesman, somewhat ominously. “It is our duty to improve safety. Safety and fun is not a contradiction.” Makes you wonder what they know that we don’t...

Basically, the problem is you lot. Sorry not to break it to you more gently, but I’m just dishing out the facts. It’s not the kids anymore like it was in the 70s and 80s. In the 00s it’s the forty-something on big capacity sportsbikes that are lending weight to the term ‘organ donors’ amongst black-humoured A+E staff. We need help. Help against ourselves.

Enter Honda, stage left, holding the burning torch of righteous technological assistance. Their combined braking electronic ABS system is now up and running on their sports models – an industry first. It may be in prototype form but, believe me, it’s ready for production. Until now ABS and combined brakes were the territory of tourers, not out-and-out sportsbikes.

Don’t be surprised to see this Dual CBS ABS system offered as an option on CBR600RR and Fireblade towards the end of this year. The price will be announced sometime soon, probably around £500. It will be an effective insurance against damaged body panels. And what price is your life?

So how does it feel?

The Combined ABS system is remarkably unobtrusive. From any speed you can stamp on the back brake pedal, grab a fistful of front and there’s no fuss or drama, no pulsating effect at either lever and no wacker-plate sensation from the suspension, front or back. Using just the rear brake pedal the CBR600 pulls up quickly with no hint of fuss or drama.

Personally I would have liked more time exploring the effect of slipper clutch downshifts and deep corner entry braking but, as we were continually reminded, this was a taster, not a test session.

Use the CBR600s brakes normally and you struggle to notice any difference between the stock bike and this kitted Dual Combined ABS set-up.

By ‘normal’ I mean front brake only. Braking power is undimished by the added circuitry and the feel is, even to my Cumberland sausage-like digits, identical to an un-equipped CBR. The only thing you can’t do is pull rolling stoppies – it just won’t allow it.

I struggled to make myself trust just the back brake pedal in isolation at the end of the fifth gear back straight. The second gearhairpin after it demanded about 80mph to be scrubbed off in the space of about 100 metres – a big ask. But, slightly surreally, the system sorts it all out for you with a strangely flat, pitchless attitude and massive retardation. You really can jump on the pedal. And still the pesky rear wheel won’t skid. I have to say that the back brake pedal doing all this weird alien stuff was the oddest feeling about the whole set up.

WHY HAS IT TAKEN SO LONG TO GET ABS FITTED TO SPORTSBIKES?

Linked brakes first reared their rusty head on Guzzis in the 1970s. Mechanical ABS plopped into the market on BMW’s loathsome K100 in 1988. It was abysmal in every respect and made a bad bike even more hateful. Hopefully, by now, all the ABS K100s are dead. Honda launched their own version of ABS on the ST1100 in ’92 and snuck it onto the ‘Wing and other gargantuan offerings. Are you seeing a pattern?

The problem with sportsbikes is a twofold one, mass (both in terms of size and weight) and their behaviour on the brakes, with a much higher polar moment of pitching inertia. In English, you brake hard and the high C of G throws all the weight forwards and downwards rolling the bike around the front wheel, creating a ‘stoppie’. For this reason the ABS system would only really work effectively in conjunction with combined braking to eliminate much of the pitch.

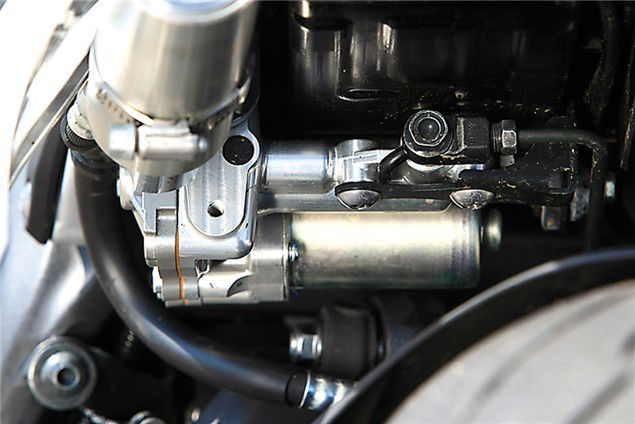

The fact that they’ve done it to a CBR600RR and it still looks like an RR is a triumph of packaging and design. The fact that it still feels like a RR (until you panic brake) is also a measure of success.

- 1. The rider grabs a big handful of front brake and stamps on the rear in an emergency.

- 2. Data from the front wheel sensor is sent to the ECU under the fairing which compares it to pre-set boundaries as well as data from the rear wheel’s sensor.

- 3. The rear wheel rises in the air

- 4. The ECU compares the data and decides if either wheel is about to lock. It senses the rear is in the air and sends a command to the control units and pressure sensors.

- 5. These sensors then alter the braking force accordingly between the two wheels via a pump, located behind the engine, connected to the brake lines. The pressure on the front brake is reduced to lower the rear wheel and keep the bike level.

- 6. The ECU senses that the rear is back on the ground, giving maximum tyre contact. Pressure is redistributed to maximise braking while ensuring both wheels aren’t locked and the rear stays down.

HOW IT WORKS

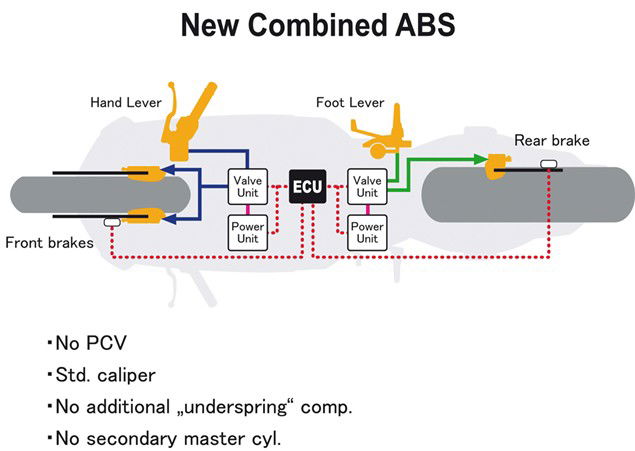

It’s all down to wheel speed sensors and a very quick thinking ECU. By sampling front and rear wheel speeds the ECU is made aware of whether a wheel is beginning to lock or perhaps a rear wheel is beginning to aviate. Based on any front-rear discrepancies, it sends its commands to the various control units, depending on what the wheel speed sensors and pressure sensors are detecting. Brake pressure at the caliper is rapidly altered depending on a steady stream of rapid sets of information. A brake fluid reservoir, modulator unit and pump cope with fluctuations in system pressure.

The system starts to work its magic once the sensors measure a certain amount of braking force. The clever part of the process is that the rider still feels like he’s in charge of the braking operation but, clearly for their own good, it’s all taken care of by the bike itself. It doesn’t matter if your hands and feet are made of lead, you will be able to perform risk-free emergency stops on polished ice without coming to grief. Very, very clever.

The combined braking system overcomes the weight pitching issue of a sports bike under heavy braking by shifting more braking effort to the rear brake and less to the front. In a both-pedal emergency stop situation the attitude of the bike is spectacularly flat, allowing maximum use of both front and rear brakes. For reasons too complicated to go into here, the system will only work above 4mph.

It’s not going to help you, though, if you’re rushing into a turn too quick, already on the razor edge of grip/disaster. Turning, leaning and braking is already asking an awful lot from a fist-sized contact patch of adhesion – the electronic redistribution of braking effort is only going to hamper this incredibly delicate situation further. Honda may be fiendishly clever but they’re not going to outsmart basic physics. Not yet, anyway.

No, it’s all about upright or near-upright emergency situations and in this area it left us all impressed. Personally I’d rather not have it because it adds at least 10kgs of weight, adds to the cost, changes the steering geometry from what my instincts expect and takes away a vital (to me) element of personal choice. But I’m a bigoted, stubborn, dyed-in-the-wool old goat.

In the greater scheme of things it’s got to be a good idea if it helps people continue breathing, as Oscar Wilde said, bad breath is better than no breath at all. In pant-filling panic moments, emergency braking doesn’t always come naturally, which is where ABS can be a life-saver.

Combined braking systems. I’ll ‘fess up straight away: I don’t like them. The lever on the right bar is to apply front brakes, the pedal under your right toes is to apply the back brake- and there it should remain. I’ve been riding bikes since I was six and 33 years of ingrained practice have obviously left me prejudiced and resistant to change. My last experience with linked brakes involved a decreasing radius left-hander somewhere near Rhyader, a VFR800 and so much unintentional opposite lock I had to sit it up and take to an open-gated field. Bastard things. And then there’s ABS – fine in cars, don’t get me wrong – but bikes? Pants. Intrusive, crude and easily confused by irregular road surfaces. Early BMW sytsems were like operating a compressed-air powered road drill across an ice rink. Not pleasant.

But, and it’s a BUT the size of J-Lo’s, there are some grizzly things happening in the European motorcycle market at the moment. Check out a graph of European car road deaths and the gentle decline looks like a cross section of a ski-school nursery slope. Nice decreasing statistics that make the roads look like a very rosy place indeed.

Speak to anyone in the emergency services and they’ll also tell you like it is. There are less fatal accidents since the introduction of safety features. Jimmy Saville’s early clunk-click campaign coinciding with the seat belt law introduction made a stellar difference. Pre-tensioners, air bags, crumple zones, safety cells, head restraints, anti-lock brakes, electronic brake distribution, traction control, electronic stability – the car list of safety devices will continue to evolve and each step of that particular Darwinian ladder makes a massive difference to both accident avoidance and protection.

The bike graph isn’t quite so pretty. It’s a bit shit, actually. For starters it goes the wrong way – upwards at an angle that is the cause of concern for manufacturers, industry in general and close relatives. But the fact that we’re splatting ourselves with increasing monotony is starting to irritate the people who control and enforce legislation. And if there’s a group of people we can’t afford to piss off too much, it’s the Brussels policy makers. Full stop. So Honda are banging their safety drum, firstly because they can and secondly to be seen to be doing ‘something’ about this grim trend.

I’m assuming the last sentence, of course. However, during the lenghty Powerpoint session we endured before actually sampling Honda’s latest effort to stem the tide of draconian legislation, there were some token sound bites hinting at the problems facing us all. “We (motorcycling in general) will only have a bright future if we improve safety”, said a Honda spokesman, somewhat ominously. “It is our duty to improve safety. Safety and fun is not a contradiction.” Makes you wonder what they know that we don’t…

HOW ABS WORKS

It’s all down to wheel speed sensors and a very quick thinking ECU. By sampling front and rear wheel speeds the ECU is made aware of whether a wheel is beginning to lock or perhaps a rear wheel is beginning to aviate. Based on any front-rear discrepancies, it sends its commands to the various control units, depending on what the wheel speed sensors and pressure sensors are detecting. Brake pressure at the caliper is rapidly altered depending on a steady stream of rapid sets of information. A brake fluid reservoir, modulator unit and pump cope with fluctuations in system pressure.

The system starts to work its magic once the sensors measure a certain amount of braking force. The clever part of the process is that the rider still feels like he’s in charge of the braking operation but, clearly for their own good, it’s all taken care of by the bike itself. It doesn’t matter if your hands and feet are made of lead, you will be able to perform risk-free emergency stops on polished ice without coming to grief. Very, very clever.

The combined braking system overcomes the weight pitching issue of a sports bike under heavy braking by shifting more braking effort to the rear brake and less to the front. In a both-pedal emergency stop situation the attitude of the bike is spectacularly flat, allowing maximum use of both front and rear brakes. For reasons too complicated to go into here, the system will only work above 4mph.

It’s not going to help you, though, if you’re rushing into a turn too quick, already on the razor edge of grip/disaster. Turning, leaning and braking is already asking an awful lot from a fist-sized contact patch of adhesion – the electronic redistribution of braking effort is only going to hamper this incredibly delicate situation further. Honda may be fiendishly clever but they’re not going to outsmart basic physics. Not yet, anyway.

No, it’s all about upright or near-upright emergency situations and in this area it left us all impressed. Personally I’d rather not have it because it adds at least 10kgs of weight, adds to the cost, changes the steering geometry from what my instincts expect and takes away a vital (to me) element of personal choice. But I’m a bigoted, stubborn, dyed-in-the-wool old goat.

In the greater scheme of things it’s got to be a good idea if it helps people continue breathing, as Oscar Wilde said, bad breath is better than no breath at all. In pant-filling panic moments, emergency braking doesn’t always come naturally, which is where ABS can be a life-saver.

Basically, the problem is you lot. Sorry not to break it to you more gently, but I’m just dishing out the facts. It’s not the kids anymore like it was in the 70s and 80s. In the 00s it’s the forty-something on big capacity sportsbikes that are lending weight to the term ‘organ donors’ amongst black-humoured A+E staff. We need help. Help against ourselves.

Enter Honda, stage left, holding the burning torch of righteous technological assistance. Their combined braking electronic ABS system is now up and running on their sports models – an industry first. It may be in prototype form but, believe me, it’s ready for production. Until now ABS and combined brakes were the territory of tourers, not out-and-out sportsbikes.

Don’t be surprised to see this Dual CBS ABS system offered as an option on CBR600RR and Fireblade towards the end of this year. The price will be announced sometime soon, probably around £500. It will be an effective insurance against damaged body panels. And what price is your life?

So how does it feel?

The Combined ABS system is remarkably unobtrusive. From any speed you can stamp on the back brake pedal, grab a fistful of front and there’s no fuss or drama, no pulsating effect at either lever and no wacker-plate sensation from the suspension, front or back. Using just the rear brake pedal the CBR600 pulls up quickly with no hint of fuss or drama.

Personally I would have liked more time exploring the effect of slipper clutch downshifts and deep corner entry braking but, as we were continually reminded, this was a taster, not a test session.

Use the CBR600s brakes normally and you struggle to notice any difference between the stock bike and this kitted Dual Combined ABS set-up.

By ‘normal’ I mean front brake only. Braking power is undimished by the added circuitry and the feel is, even to my Cumberland sausage-like digits, identical to an un-equipped CBR. The only thing you can’t do is pull rolling stoppies – it just won’t allow it.

I struggled to make myself trust just the back brake pedal in isolation at the end of the fifth gear back straight. The second gearhairpin after it demanded about 80mph to be scrubbed off in the space of about 100 metres – a big ask. But, slightly surreally, the system sorts it all out for you with a strangely flat, pitchless attitude and massive retardation. You really can jump on the pedal. And still the pesky rear wheel won’t skid. I have to say that the back brake pedal doing all this weird alien stuff was the oddest feeling about the whole set up.

Why has it taken so long to get ABS fitted to sportsbikes?

Linked brakes first reared their rusty head on Guzzis in the 1970s. Mechanical ABS plopped into the market on BMW’s loathsome K100 in 1988. It was abysmal in every respect and made a bad bike even more hateful. Hopefully, by now, all the ABS K100s are dead. Honda launched their own version of ABS on the ST1100 in ’92 and snuck it onto the ‘Wing and other gargantuan offerings. Are you seeing a pattern?

The problem with sportsbikes is a twofold one, mass (both in terms of size and weight) and their behaviour on the brakes, with a much higher polar moment of pitching inertia. In English, you brake hard and the high C of G throws all the weight forwards and downwards rolling the bike around the front wheel, creating a ‘stoppie’. For this reason the ABS system would only really work effectively in conjunction with combined braking to eliminate much of the pitch.

The fact that they’ve done it to a CBR600RR and it still looks like an RR is a triumph of packaging and design. The fact that it still feels like a RR (until you panic brake) is also a measure of success.

- The rider grabs a big handful of front brake and stamps on the rear in an emergency.

- Data from the front wheel sensor is sent to the ECU under the fairing which compares it to pre-set boundaries as well as data from the rear wheel’s sensor.

- The rear wheel rises in the air

- The ECU compares the data and decides if either wheel is about to lock. It senses the rear is in the air and sends a command to the control units and pressure sensors.

- These sensors then alter the braking force accordingly between the two wheels via a pump, located behind the engine, connected to the brake lines. The pressure on the front brake is reduced to lower the rear wheel and keep the bike level.

- The ECU senses that the rear is back on the ground, giving maximum tyre contact. Pressure is redistributed to maximise braking while ensuring both wheels aren’t locked and the rear stays down.