Godfather of the Modern Scooter | Corradino D’Ascanio

D’Ascanio was not just responsible for the style and success of the very first Vespa, he was largely responsible for its chief rival, Innocenti’s ‘Lambretta’, too.

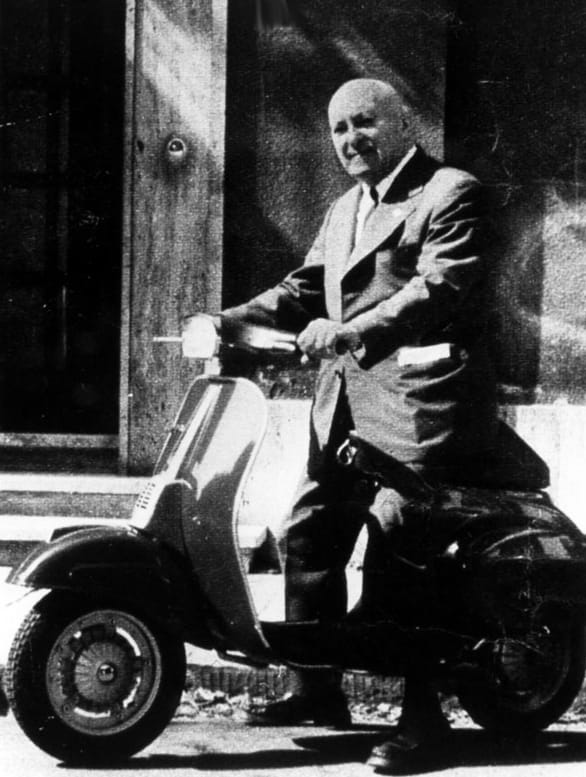

Elsewhere we’ve reported that this week marks the 75th anniversary of Vespa, which launched its very first scooter in 1946. But we couldn’t let this commemoration pass without also celebrating the man most responsible for the original Vespa scooter – and by association the creation of not just one of the biggest brands in motorcycling and also the style and success of a whole genre of powered two-wheeler – Corradino D’Ascanio.

What’s more astounding still is that D’Ascanio was not just responsible for the style and success of the very first Vespa, he was largely responsible for its chief rival, Innocenti’s ‘Lambretta’, too – not bad for a designer who actually had little interest in motorcycles and whose primary focus was aeroplanes, helicopters and aeronautics….

… although then again, it was probably that very dislike of motorcycles which helped shape his scooter design in the first place!

D’Ascanio was born in 1891 in Popoli, Pescara, Italy, had a passion for flight and mechanical design and engineering from a very early age (to the extent of even designing his own glider at the age of 15), then later studied mechanical engineering at the ‘Politecnico di Torino’ (Polytechnic of Turin).

After graduation with his degree in 1914, D’Ascanio joined the military working largely as a designer and engineer, then, following the end of WW1 hostilities, he returned to Popoli. There he began to specialise in early helicopter control mechanisms, taking out a number of patents and, after setting up his own company in 1925, he built one of the very first successful helicopters, a twin rotor design, in 1930.

D’Ascanio’s company, however, collapsed during the depression that encompassed the rest of that decade, partly due to Fascist dictator Mussolini’s focus on more traditional industries, and he instead joined Piaggio, then a specialist aircraft manufacturer, where he focussed on high speed, adjustable pitch propellors.

During WW2, D’Ascanio’s helicopter development work at Piaggio was considered so important he was promoted to the rank of general. However, wartime defeat at the hands of the Allies destroyed both Piaggio’s factories and scuppered D’Ascanio’s aeronautical ambitions as Italy was subsequently bound to an agreement to not research or produce military or aerospace technology for a 10-year period.

However, the rubble and ruins of WW2 also created a unique set of circumstances that would prove formative for, not just the creation of Italian scooters but also for the founding of a whole series of utility motorcycle manufacturers.

In Japan, Soichiro Honda began producing rudimentary powered bicycles as an affordable form of post-war transport.

Similarly in Italy, the now unemployed D’Ascanio was approached by Ferdinando Innocenti, a pre-war tubing manufacturer, who had a vision for what would become the motor scooter to fulfil a similar role.

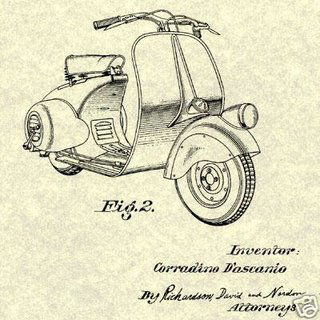

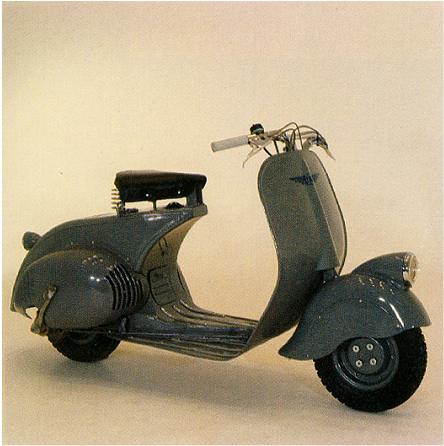

Innocenti’s brief for D’Ascanio was famously to build a powered two-wheeler that would be easy to ride for both men and women, be able to carry a passenger, and would not get its driver's clothes dirty. For D’Ascanio, who hated motorcycles, it was the perfect brief and resulted in a revolutionary vehicle. His resulting design featured a single spar frame with the engine mounted directly on to the rear wheel. There was front protective ‘leg shield’ to keep the rider dry and clean, and the machine’s ‘step-thru’ design made it easy for all riders to get on board, including women, whose skirts made riding a motorcycle a challenge. A novel handlebar gear change was also intended to be easy to use for all while the internal mesh transmission eliminated the oil and dirt of a conventional motorcycle chain.

Unfortunately for Innocenti, however, D’Ascanio also favoured a pressed steel frame where Innocenti, hoping to revive his pre-war business, prescribed a tubular steel one. As a result, the pair fell out before what would become the Lambretta, was finished.

D’Ascanio instead took his ideas to Piaggio, who were in the throes of developing their own post-war two-wheeler but who’s initial designs had so far proved unsatisfactory. The resulting machine – the first Vespa (as named by Piaggio boss Enrico Piaggio due to its supposed similarity to a wasp) was patented in 1946 before first going on sale in 1947, just before the first Lambretta, which needed to be redesigned and ran into production difficulties. And the rest, as they say, is history. The Vespa lives on today as the definitive scooter and as a fashion icon in its own right. Innocenti, meanwhile, closed in 1972, although various Lambretta reincarnations have been attempted since…

For D’Ascanio, however, it was the end of his motorcycle and two-wheeler associations as he returned to his first love – aeronautics. He remained at Piaggio, albeit in its heavily restricted and damaged aeronautics division, where he mostly helped update older designs. These restrictions, however, also meant that Piaggio fell behind the latest developments in aircraft and helicopter technology and few of D’Ascanio’s designs actually made it off the drawing board.

Frustrated, D’Ascanio finally left Piaggio in 1964 to join the Agusta Group, then Italy’s largest helicopter manufacturer (and who, in 2000 merged with the UK’s Westland to form Agusta Westland, which in turn became Leonardo in 2015). In 1969 D’Ascanio designed a small training helicopter, the Agusta ADA, although it was never fully developed. And throughout this period D’Ascanio was also a respected author of numerous scientific papers and a professor of design at Pisa University.

In recognition of these endeavours, for his services to Italy and to aeronautical development, D’Ascanio was awarded the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic by the Italian President.

Publicly, however, and to his lifelong annoyance, D’Ascanio has always been more greatly recognised and celebrated for his role in the creation of both the Vespa and Lambretta, and indeed the whole scooter concept rather than for his inventions and patents in the world of helicopters and aeronautics.

D’Ascanio died in Pisa in 1981 known, not as the father of the helicopter, as he would have wished, but as the father of the scooter. Not that the thousands if not millions of Vespa and Lambretta fans are complaining…!