How it works – slipper/assist clutches | The MotoGP tech now found on road bikes

Visordown takes a deep dive into slipper clutches, the MotoGP tech we can now find on almost any road bike

TRIUMPH'S new Speed Triple 1200 RS is, as expected, a quantum leap forward for the British super naked in terms of performance and spec, but it’s also another example of bikes now routinely being fitted with a ‘slip and assist’ clutch – a clutch type that has quickly become the norm. But what are they exactly?

Most of us are familiar with the idea of a ‘slipper clutch’. As with many technological advances they were developed in racing to improve performance – but not for speeding up, but when slowing down.

Most of us are also almost certainly aware of ‘engine braking’, the means of slowing a bike by closing the throttle, the reduced engine speed then ‘braking’ the rear wheel through the chain or shaft. (It’s worth mentioning here, incidentally, that engine braking is far more prevalent in four-stroke engines, especially larger capacity, longer stroke ones. It inherently hardly exists at all in small capacity two-strokes…)

In extreme cases, such as when racing, particularly when combined with rapid downshifts, this engine braking can cause the suddenly slowed rear wheel to ‘hop’ making the bike unstable when about to tip into turns. Not ideal when you want to out brake the leader into the final turn… (Extreme downshifting could also damage the gearbox and force the engine to over-rev while it was also increasingly noticed that some racers were increasingly pulling in the clutch into turns to avoid the issue, a distraction they could probably do without…)

‘Slipper’ clutches were developed to reduce these effects. The mechanics vary but the principle is the same: to progressively disengage or ‘slip’ the clutch when the rear wheel tries to ‘drive’ the engine faster than it would under deceleration.

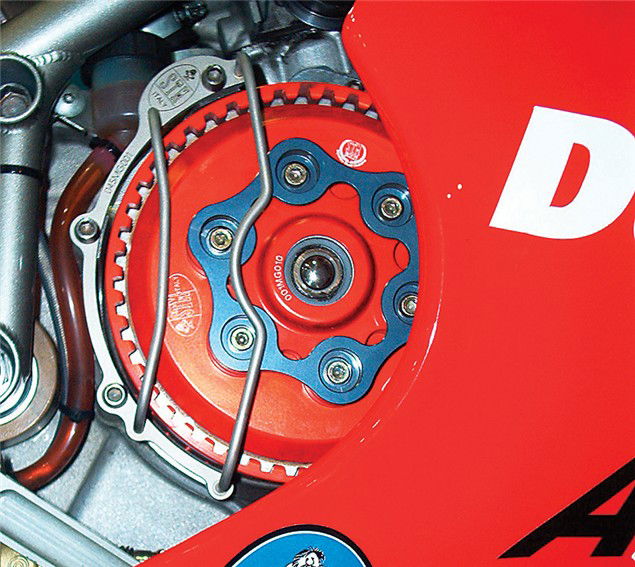

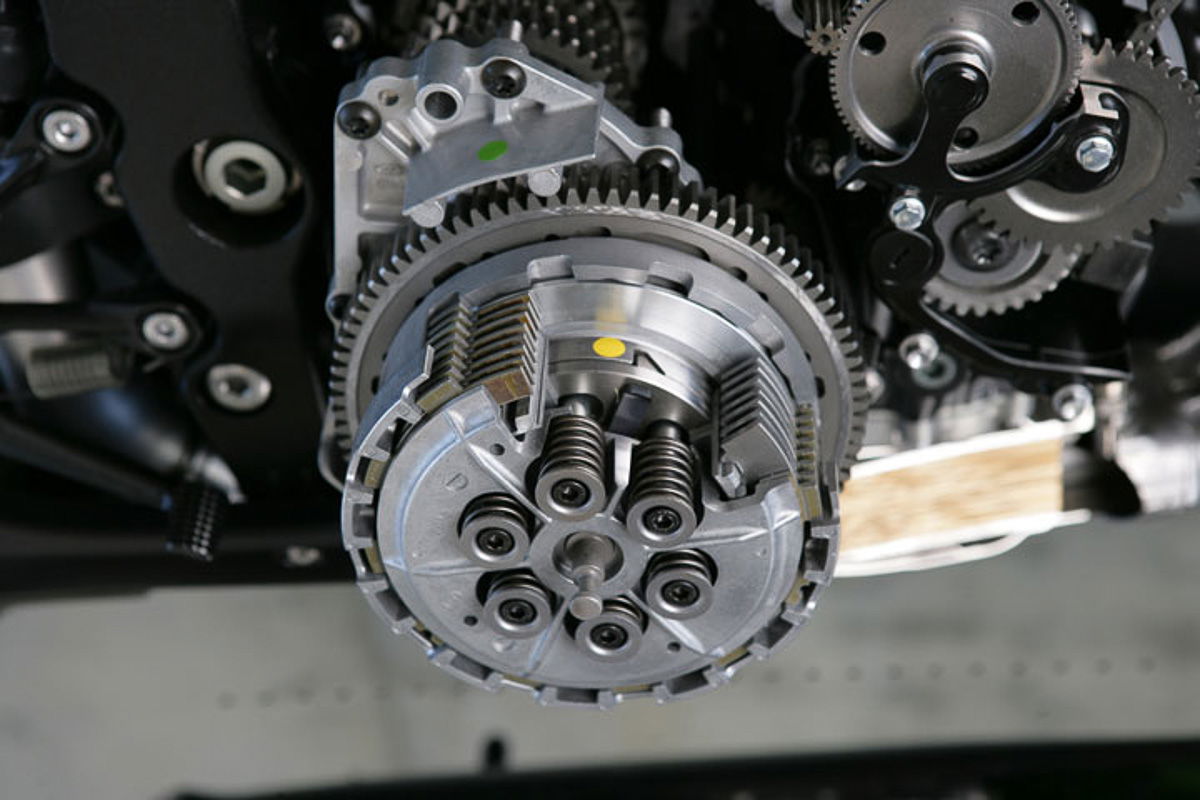

This is achieved by having a mechanism in the clutch centre which progressively disengages the clutch basket from the clutch centre according to the amount of ‘back torque’.

Different terms and designs are used, but essentially a series of angled ‘ramps’ are used on the clutch faces which are meshed together under normal loads but are increasingly pulled apart, disengaging the clutch, under reverse loading, causing clutch ‘slip’ so allowing the rear wheel to rotate.

So far, so slipper clutch.

The more recent advance of this is the addition of the ‘assist’ element. Engineers realised that an opposite effect of a slipper clutch’s ramps unmeshing under back torque would be their enhanced meshing under normal loads. In other words: when a bike is being ridden forwards normally with the engine and transmission rotating in the usual manner the engine’s forward torque could be mesh the ramps tighter together, increasing clutch engagement and so reducing the need for heavy clutch springs. As a result, lighter clutch springs can be used which in turn lightens the pull required from the rider on the clutch lever. In other words: the clutch is ‘assisting’ the rider – hence ‘assist clutch’

All of that is, of course, very welcome in theory. In practice, the cynic in me suggests you probably won’t notice the ‘assist’ function unless you compare similar bikes with it and without, while the slipper element, on the road at least, only really has value if you ride like a loon. Sounds good as a marketing tool, though…

Sponsored By

Britain's No.1 Specialist Tools and Machinery Superstores

When it comes to buying tools and machinery, you need to know you're buying from specialists who know what they're talking about.

Machine Mart eat, sleep and breathe tools and machinery, and are constantly updating their range to give you the very best choice and value for money - all backed by expert advice from their friendly and knowledgeable staff. With superstores nationwide, a dedicated mail order department and a 24 hour website offering quality branded items at fiercely competitive prices, they should be your first choice for quality tools and equipment.

.JPG?width=1600)