Electric off-road bikes boom, while road-going models bust

As off-road electric bikes are going from strength to strength, road-legal electric bike sales are plummeting - but why?

Electric motorcycle manufacturing seems to be a bit of a two-wheeled ot potato. Many have tried to build an electric motorcycle to ‘change the game’ or ‘set a new standard’ of battery-powered bike ownership. But few have succeeded, and many fall at the wayside before they’ve even got into their stride.

But that’s only one side of the coin, and there is a world in which electric bikes aren’t just surviving, they are thriving. Off-road motorcycles powered by batteries are in something of an ascendancy as we head into 2026. Stark Ventures, the makers of the Varg and Varg EX, just posted record end of year results, reaching €115 million (around £100 million) in revenue in 2025. Oset, which was recently acquired by Triumph, remains a favoured brand for people looking to get into trials riding, and brands like Sur-Ron and Talaria seem to make enough that they can continue to innovate, even if their bikes are seen more often on a high street being ridden illegally than on a private trail or track.

In contrast to that growth, we have brands like LiveWire, which, according to its 2025 Q3 investor report, made just 184 bikes between July 1 and September 30. In fact, if it weren’t for LiveWire adding its StayC kids’ balance and dirt bikes to the range, things would have been much worse. And LiveWire is not alone in having a tough time in the market, with the long-time leader of the pack, Zero Motorcycles, posting equally meagre numbers of around 2,000 bikes. Zero has made the sensible step of moving into the off-road sector - joining Sur-Ron, Talaria, and Stark Ventures - although it’s too early for the American brand to reap the rewards of the move.

So what is it about using an electric bike on the road instead of a petrol bike that is such a turn-off?

The answer to that is as complex as it gets.

First off, motorcycling is a very broad church. From everyday riders to those summertime-only weekend warriors, commuters to adventure fans, tourers to trackday riders. What works for one won’t always work for another. From talking to riders at shows and events, the biggest stumbling block that almost all can agree on, though, isn’t about usability, or how well an electric bike meets their needs. It’s emotion.

Electric bikes simply don’t stir the soul quite like a petrol bike does. Thumb the starter of a two or four-stroke motorcycle, and the engine spins up, turning fuel and air into fire, energy, noise and emotion. A petrol engine, be it at tickover or full chat, is as close to a living, breathing thing as metal and moving parts can get. And no amount of synthesised engine sounds or faux gear shifts can change that.

And the story doens’t get any better when we step away from the world of emotivity.

The range of most electric bikes isn’t where many feel it should be, and the recharge time is, in many cases, not much better. Battery swapping is an obvious place to start in a quest to improve both of those factors. GoGoro has been doing it for years, and Kymco has its own take with Noodoe charging stations. Even the biggest of them all, Honda, has got in on the battery swapping scene - just not quite on this side of the world yet. The principle is refreshingly simple: roll up with a near-flat battery, authenticate yourself, pull out a fully charged unit and slot it straight into the bike. Job done and ride off.

The big win here is time. A swap can take less than a minute, compared to the 20 minutes or more that even the fastest fast-charging electric bikes still demand. That changes rider behaviour entirely. If stopping is painless, stopping often isn’t an issue. Taiwan is the poster child for this approach, where a huge proportion of two-wheelers are already electric and battery swapping is just part of daily life.

For it to work globally, though, manufacturers would need to agree on standardised battery sizes and formats. That’s a big ask, but the payoff could be lighter bikes, better handling and less obsession with headline-grabbing range figures that most riders don’t actually need.

This one sounds like sci-fi, but the fundamentals are already familiar. If you’ve ever dropped your phone onto a wireless charging pad, you already understand the idea. Inductive charging roads would continually top up an electric bike, or any other EV, as it’s being ridden, transferring energy wirelessly through the road surface. The same Qi-style principles apply, just scaled up. The holy grail here is that bikes wouldn’t need massive batteries at all, only enough capacity to bridge the gaps between inductive sections of road.

If it ever became widespread, the knock-on effect would be smaller batteries, lighter bikes and far fewer compromises in how an electric motorcycle looks and rides. It’s a long way off, but it’s not nonsense.

Hydrogen is another option that sounds more far-fetched than it actually is. Suzuki already has a working hydrogen fuel cell Burgman scooter, which proves the concept isn’t theoretical. It just hasn’t been industrialised at scale.

At its core, a hydrogen fuel cell generates electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen, producing water as the only by-product. No combustion, meaning no emissions at the tailpipe. The electricity generated then drives an electric motor, just like a regular battery-powered bike.

The challenge here isn’t whether it works, but infrastructure, cost and public acceptance. As with electric charging, without somewhere easy to refuel, it remains a niche solution.

What about hybrid motorcycles?

.jpg?width=1600)

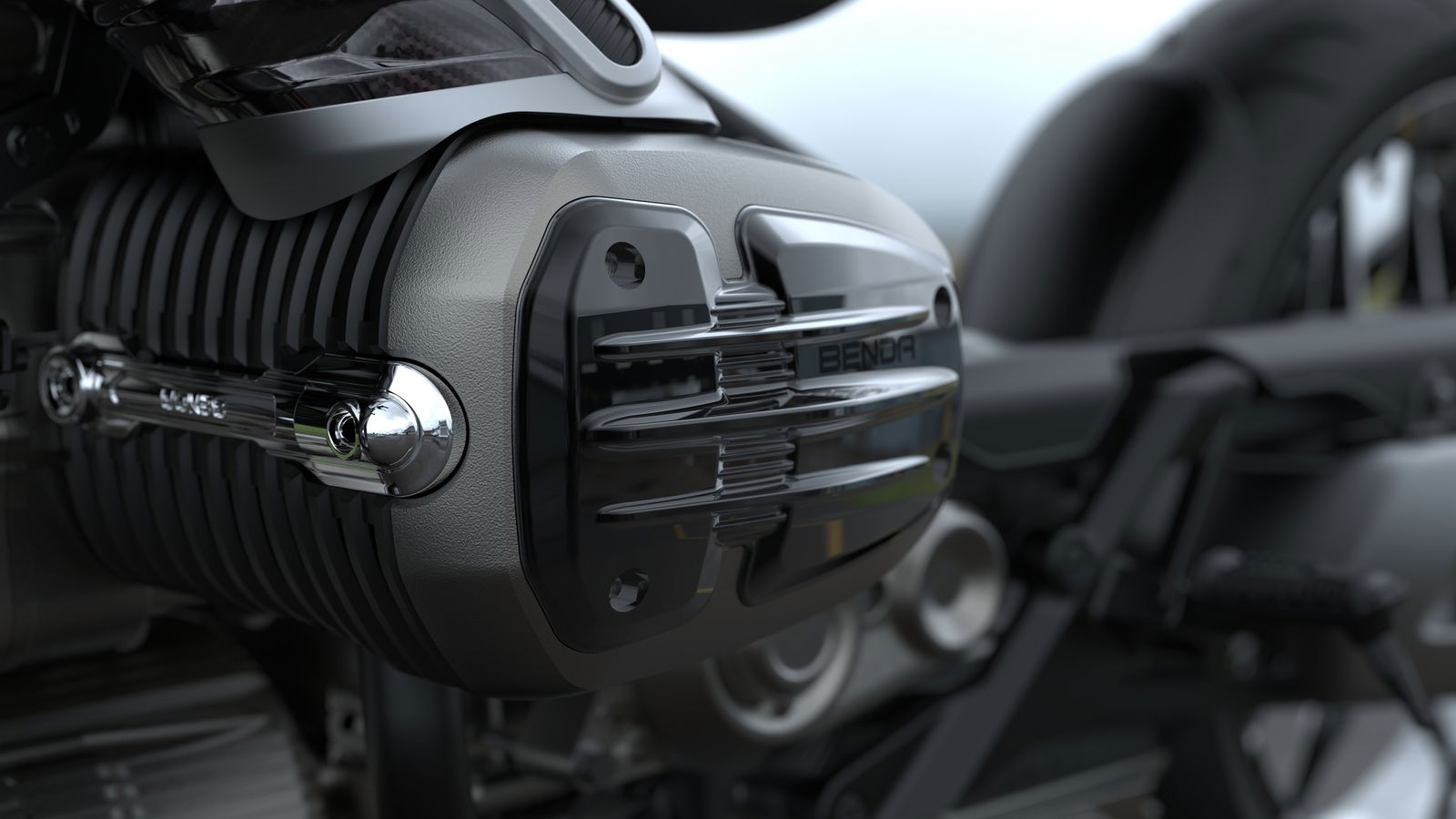

Hybrids are everywhere in the car world, yet in bikes, they’re almost non-existent. Kawasaki has tried with its Ninja 7 Hybrid and Z7 Hybrid models, and Benda has a hybrid motor in the works too. On paper, they make a lot of sense. A small petrol engine could handle longer runs and recharge the battery, while electric power could take over in towns or for short hops.

The problem, once again, is weight. Even a modest petrol engine adds serious mass, and when you stack that alongside an electric motor, batteries, power electronics and a system to blend the two, things spiral quickly. You’re looking at around 100kg of drivetrain hardware before you’ve even started building the bike around it.

Cost doesn’t help either. Merging petrol and electric systems isn’t cheap, and price is already one of the biggest sticking points for riders sceptical about electric bikes. Until someone finds a way to make hybrids light, simple and affordable, they’re likely to remain an engineering curiosity rather than a showroom staple.

Electric motorcycles, then, are not failing across the board, they’re just succeeding in very different places. Away from the road, where silence is an advantage, range expectations are shorter, and outright performance matters more than romance, battery power is proving its worth. Off-road electric bikes are lighter, simpler, and easier to integrate into how they’re actually used, which explains why brands in that space are growing while road-focused manufacturers continue to struggle for traction.

On the tarmac, though, the hurdles are as much emotional as they are technical. Range anxiety, recharge times and infrastructure gaps all play their part, but the deeper issue is that road riders still expect their bikes to deliver a sensory experience that electric power has yet to replicate. With that in mind, is the solution to reducing fossil fuel dependence staring us in the face? Hydrogen fuel could be the answer to all this, if we switched to using another combustible fuel that also just happens to be highly abundant on this planet we call Earth.

We can but dream.

Find the latest motorcycle news on Visordown.com