BMW Tech day - 3D printing technology

Another hot tech take from our day at BMW's R&D Centre in France

IF YOU listen to some futurologists, they reckon that 3D printing - or 'additive manufacture' will take over everything in the not-too-distant future. The theory seems simple enough - 'printers' like the inkjet ones we've all been using for decades to print on paper are modified to print out solid metal or plastic instead of ink. These devices build up components from computer-designed plans, in thin layers, until the whole part is produced. This allows the maker to customise parts, make unique personalised designs, and produce shapes which would be very hard - or impossible - to make in any other way.

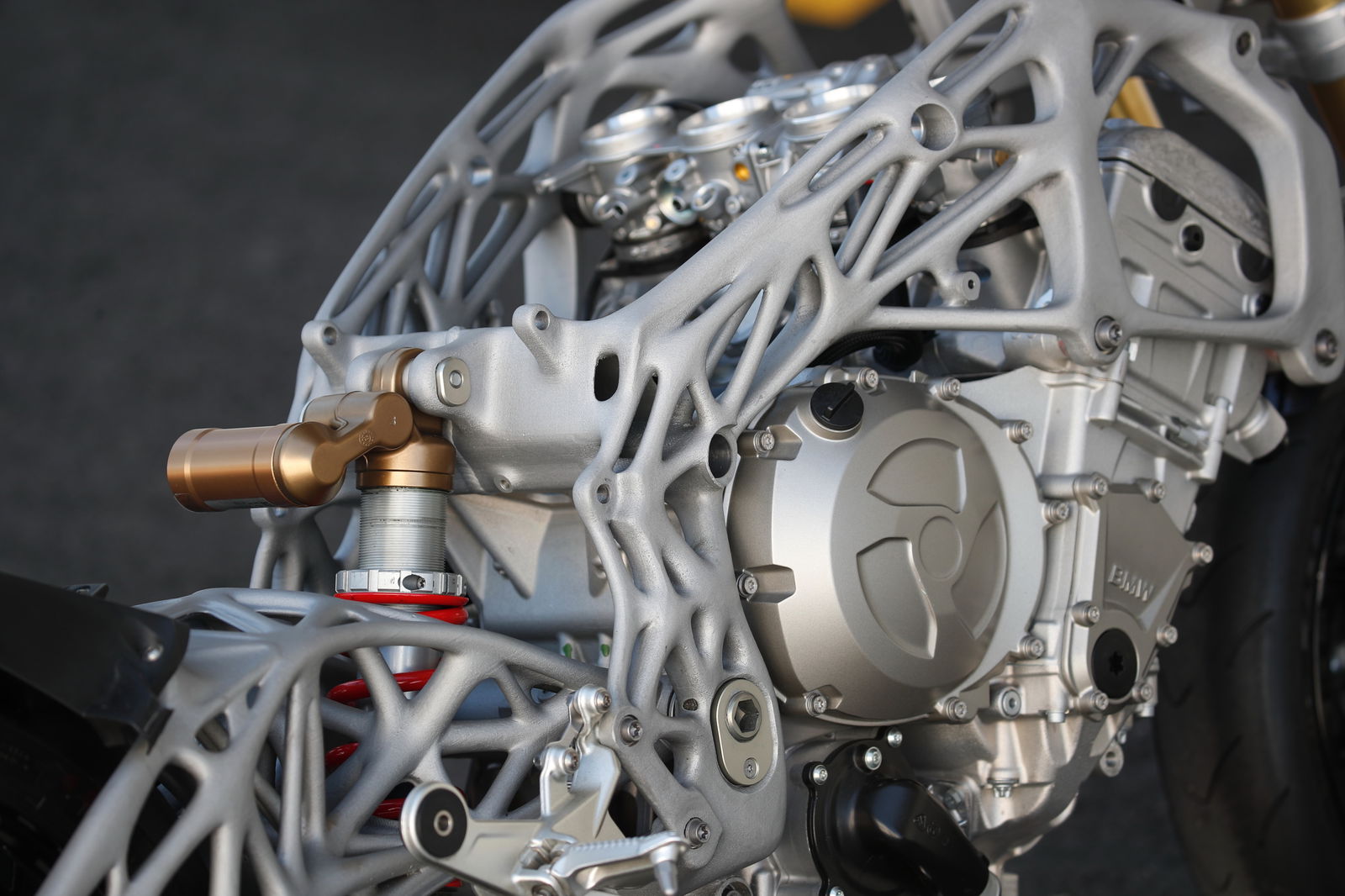

BMW showed off its own 3D-printed S1000RR frame and swingarm at its Technology day in Marseille last week. We'd seen this before - but not in real life, only in photos. And it's fair to say it's an impressive thing when you see it up close and touch it. The video above shows how it's made - lasers melting metal powder in thin 50 micron layers, to produce the frame in three parts. There are two frame 'rails' and a headstock, which are then welded together. The curious 'organic' shape is computer-designed to resolve all the forces going through the frame in an ideal manner, while keeping excess material - and mass - to a minimum.

The frame is an amazing thing - although it's really just for show. No-one has ridden the bike with it, and it would be a massively expensive way of making a frame. BMW used a machine costing nearly £1m to build it, and it took five days...

One of the firm's 3D speciaists, engineer Torsten Burkert, took us through how BMW currently uses 3D printing, and how it will develop over time. He emphasised that it's unlikely to take over from conventional casting, forging and other mass production techniques - it's still cheaper to stamp out metal parts in the old-fashioned way when you want thousands of them made in a short period of time.

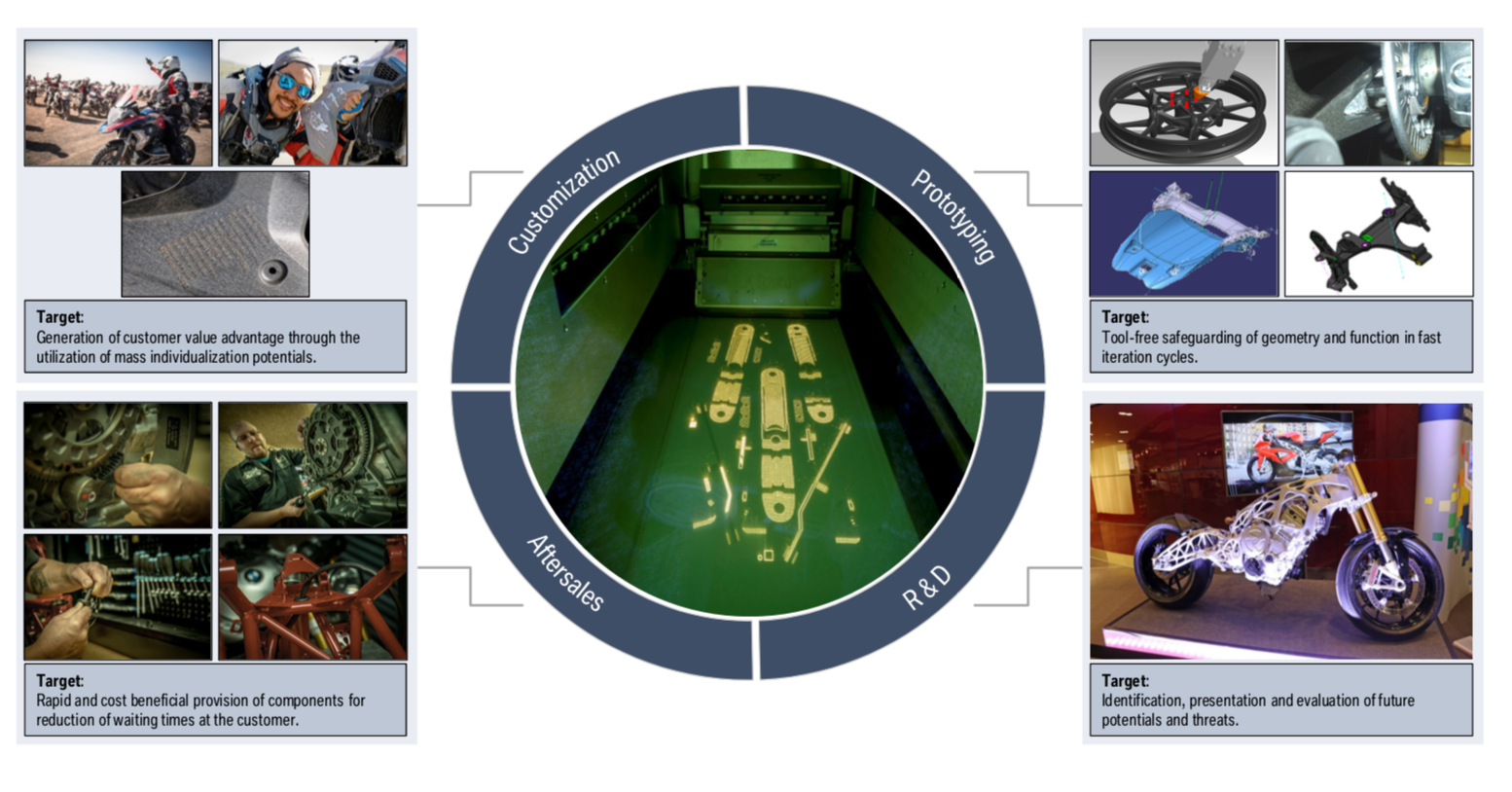

Where 3D printing works is in four separate areas - R&D, customisation, prototyping and in aftersales. With R&D and prototypes, 3D printing lets engineers try out different components quickly and easily. So a range of different possible parts could be rustled up on a 3D printer, then tested on a dyno or on the road. The best one will then be made in conventional production lines, far cheaper than the printing method could manage.

Customisation is happening in the car world now - BMW's MINI range can be ordered with the owner's name printed into dashboard inserts. And there's scope for restorers and retro bike fans to get new parts for old bikes which are no longer available. Reverse-engineering will let BMW make new parts from rusted, broken or worn old components - meaning you could get some brand-new footrest brackets for your 1970s Boxer, or the like.

We're not likely to be riding around on 3D-printed bikes anytime soon then, despite what the future geeks might tell you. But for engineers at firms like BMW, the technology is becoming more and more useful in developing the bikes we will be riding. And at the edges, we might see some niche applications of the tech creeping in for the end users like us.