Triumph Speed Twin 1200 (2019) review

Hinckley goes back to the future with high-value, performance-orientated modern classic

YOU KNOW how sometimes you see someone on the telly and think ‘surely they died years ago?’? I sort of did that a bit when I saw the press release about the Triumph Speed Twin last year. In the same way that I kept thinking Dick van Dyke has gone to the great Cockney accent school in the sky, until he appeared in the new Mary Poppins film, I thought Triumph had done this before. After all, we’ve had a Speed Four, (loads of) Speed Triples, and I knew there was a Speed Twin from way back in the day. Surely in the huge slew of Bonneville-based specials that have appeared in the modern Triumph pantheon there’s been a Speed Twin at some point?

But no – I was well wrong. This is the first time Triumph has resurrected that particular part of its ‘eritage. Which is a surprise – the 1938 Speed Twin was a massive part of the firm’s history, bringing the parallel twin engine layout to its lineup, and setting out the pattern for much mainstream British motorcycle design in the post-WW2 period.

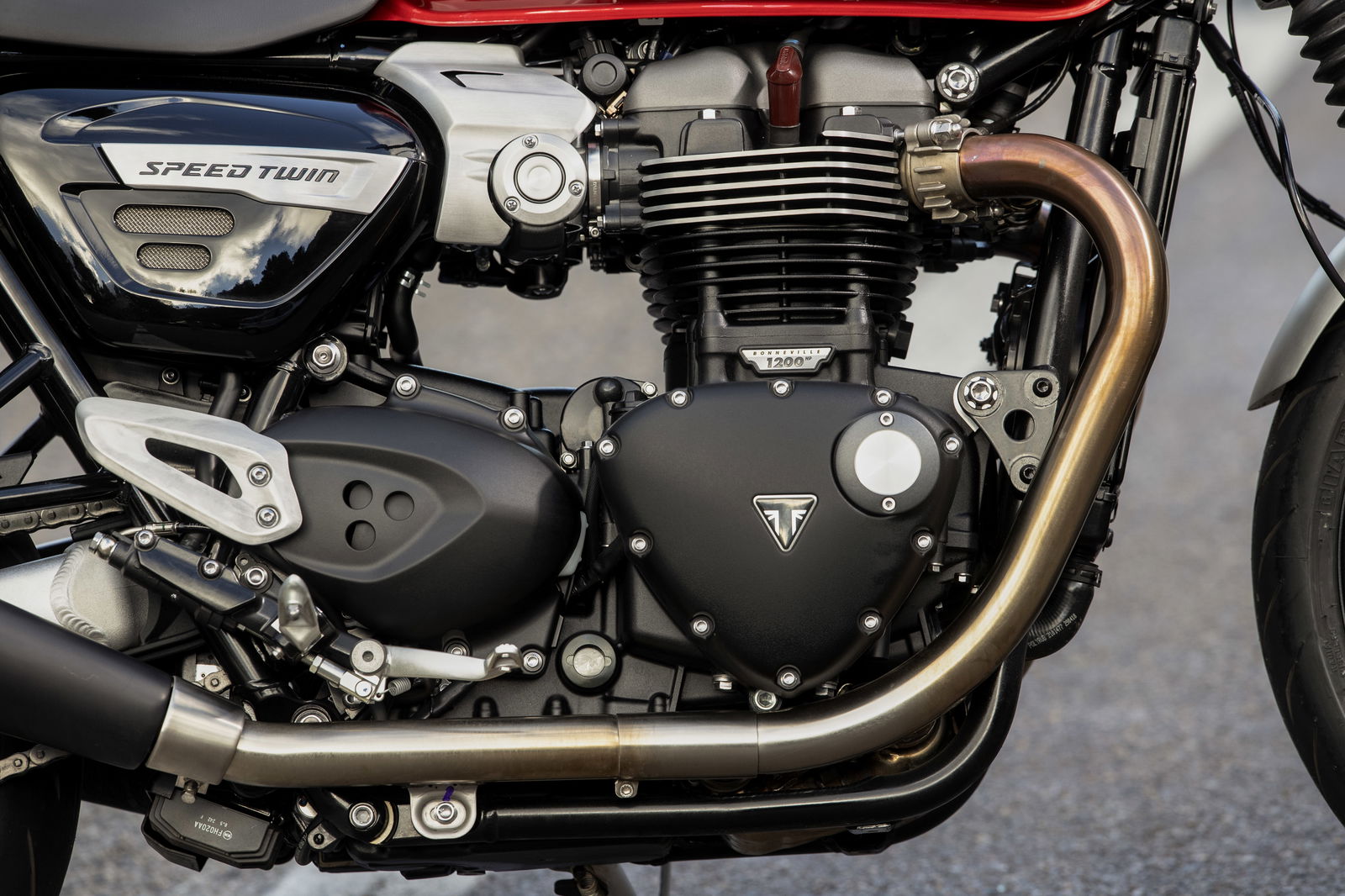

This new bike isn’t nearly as revolutionary as the original (despite the PR claims in the technical briefing). But parked up outside the posh Hyatt hotel in Mallorca where we’re about to go for a ride, it’s looking pretty good. The fundamental layout is simple enough – Triumph’s liquid-cooled 1200 parallel twin Bonneville engine, in a high-power ‘Thruxton’ tune (as opposed to a high-torque ‘Bonneville’ tune), with a cradle frame, conventional suspension, cast wheels and non-radial Brembo brakes.

But Triumph’s also given it a pretty slick styling package, with some neat high-quality touches – brushed aluminium mudguards, forged alloy headlight bracket, Monza fuel cap, smart alloy swingarm, aluminium trims on the sidepanels and a hand-coachlined fuel tank. Behind the retro style is a decent helping of tech and rider aids – power modes, switchable traction control, ABS and useful trip computer functions. Smart.

So far, so familiar. Especially to fans of the current Thruxton and Bonneville T120 ranges. But there are a load of detail changes which make this Speed Twin more different than you might think. The Triumph PR-speak focussed on weight loss as a big factor in the design – so that cradle frame has an aluminium bottom section, making it a hybrid design, the wheels are a super-light cast aluminium design, and the old-spec lead-acid battery is replaced by a lighter sealed unit.

In addition, the engine has also been fettled to cut mass. The crank is lighter, the cam cover is now lightweight magnesium, and there’s a new clutch with reduced mass. The power output is the same as the Thruxton unit, making 96bhp, but the new motor is 2.5kg lighter. Overall, in fact, the whole bike is 10kg lighter than a Thruxton, which is impressive stuff.

The rest of the chassis is also tweaked compared to the Thruxton – 15mm more wheelbase (just via a longer chain run; the swingarm is the same), 0.1 degree rake kicked out and a more relaxed riding position with lower, more forward pegs.

Enough of this navel-gazing stuff though – time for a spin. We’re at the northern end of Mallorca, and have a full day of riding planned, taking in the entire ‘six times the size of the Isle of Man’ Balearic island. We’ve got ex-BSB racer Pete Ward leading us out, a selection of nutty fellow Brit journos, and a full 14.5 litre tank of gas. Let’s go!

The Speed Twin is a decent place to be, right from the off. There’s nothing unusual or weird – a natty twin-clock dashboard, wide alloy bars with mirrors on the end, big flat comfy bench seat and a fairly low (807mm) seat height. Pulling out of the Hyatt, the engine immediately wakes you up with a strong, grunty snarl right off idle, and you’re very aware that you’re on a fairly serious, torquey machine. A few miles of pottering along some dual carriageway settles us in, then the indicators come on and we head for the hills.

The Speed Twin is a big-boned beast of a bike when parked up, but it’s commendably low on weight (196kg dry). And what mass there is does a disappearing trick fairly sharpish. It’s nimble for its size, and the Brembo brakes have good initial bite: just as well, as we soon hit some very tight hairpin bends. The Pirelli Diablo Rosso III rubber warms up quickly too, but I’m still glad we’ve got full ABS and traction control safety nets in place early doors. The sun’s up and it’s getting warmer, but there are loads of damp sections in the shadows, and the Tarmac temperatures won’t have risen much yet.

The engine is dominating the experience though. On paper, an SOHC motor with such a long stroke (bore and stroke are 97.6x80mm) should be quite lazy, and indeed, much of the best stuff is low-down in the range. But hold onto the revs for a bit and get up towards the low 7k redline, and there’s a decent amount of top end too. Fuelling is clean, and it’ll hoik up a very decent wheelie with a whiff of clutch and some dogged determination. Don’t do too many though, or the ABS turns off and the engine warning light comes on, making you think you’ve broken it (ask me how I know). The slipper clutch works a treat, letting you bang down a load of gears into a bend without locking the back, and the gearchange itself is smooth and positive.

The sector benchmark here is probably the BMW 1,170cc Boxer engine (the old oil-cooled R1200 lump), and while that has around 10bhp more peak power, and extra revs, I think the Speed Twin’s low-down urge puts it on a par with the Bavarian Boxer, in most situations. Losing the shaft final drive saves mass of course, and there’s also lower frictional losses from a chain, meaning the power figures of the two designs could well be much closer on a dyno than on a factory spec sheet.

On these super-twisty mountain roads, you quickly get into the groove – hard on the brakes, down into second, hoon round the bend enjoying the ample ground clearance, then bang the gas back on as hard and as soon as you can manage. The rear tyre is a comparatively narrow 160/60 section, and that seems to help with the agility, while the steering geometry itself is slightly more relaxed than a Thruxton. The result is a very natural-feeling chassis that’s good fun to push hard on.

Head to page two for the rest of the review >>>