Behind the scenes of Norton’s next generation bikes

Behind the glitz, glamour, and classic bikes of the Norton factory foyer lies a team of engineers armed with high-tech tools who are quietly building the next chapter.

The recent history of Norton is not its finest chapter, with mismanagement, corporate greed and failed promises dominating the headlines. We won’t go over the specifics of that story here; it has been well-documented enough in recent years. We will, however, take a look at where Norton is heading and hopefully gain some insight into its trajectory.

To do that, Norton invited me to its Solihull HQ, a small (in the grand scheme of things) factory nestled in the corner of an industrial estate a stone’s throw from the M42. And I say small because it is. Sure, at between 70,000 and 80,000 square feet in size, it’s a very big building – a few five-a-side pitches would happily fill it with room to spare. But in motorcycle manufacturing terms, it’s a minnow, so I was keen to find out how Norton was going to fit in all the new bikes and bold claims.

We started the morning with a tour of the facility. I’ve been to Norton twice since TVS took over: once at the very beginning, when the end-of-line V4 and Commando models were being rolled out, and again just after EICMA 2025. As I stepped into the factory for this third visit, the factory floor had once again changed.

It was bustling, but not to the sound of air tools and engines. Today, it was buzzing to the sound of electric saws, hammers, and drills, as workers hacked into plasterboard offices to once more reshape the space. With all the demolition going on and dust sheets draped over work areas, the Norton factory felt smaller than it ever had before.

I asked Simon Riley, Norton’s Continuous Improvement Lead – and our de facto tour guide for the day – if there was room in Solihull to grow within this relatively small building.

“It’s not too difficult to reallocate space if we need to,” he replied with a distinctive Midlands twang. “We’ve got some off-site facilities [now]. For example, we used to have the service workshop on-site, which is now off-site.” That off-site space is also set to evolve, with Norton turning it into a kind of one-stop shop for dealer training and servicing bikes when required.

Making those kinds of changes possible is the wealth of knowledge and expertise in the region. JLR, Bentley, McLaren, and not forgetting Triumph, are all within easy reach of Solihull. On top of that, Norton is in the engineering and technical heartland of the UK. That makes upskilling a workforce with ready-trained and experienced hands a much easier task.

“We’re in the engineering hub of the UK, we’re utilising the skills that are in the area to help us with engineering, developing and producing the bikes.”

Skilled hands are one thing – a thing that I’m sure the previous iteration of Norton also had – but clever tools are a very different thing altogether. Helping Norton weed out some of the production issues that blighted many Garner-era bikes is a high-tech tooling solution that quite literally records every nut, bolt and torque setting. To me, it looks like any other battery-powered digital torque wrench, but it’s actually a small part of an engineering hive mind that logs and tracks every fastener on every bike produced.

The system effectively tells the engineer which bolt to work on next and, because it knows what is next, it also understands the torque setting that is required – it even knows how many revolutions are needed. It can also tell if a fastener has been cross-threaded or incorrectly torqued. The system means that, for any bolt on any bike produced in the factory, technicians can drill down into the data and see when it was tightened, who worked on it, what they had for lunch, and the last time they went to the loo.

The last two are obviously jokes, but you get the picture. Norton is taking traceability down to a granular, almost molecular level. It isn’t the kind of thing you’d have found at Donington Hall.

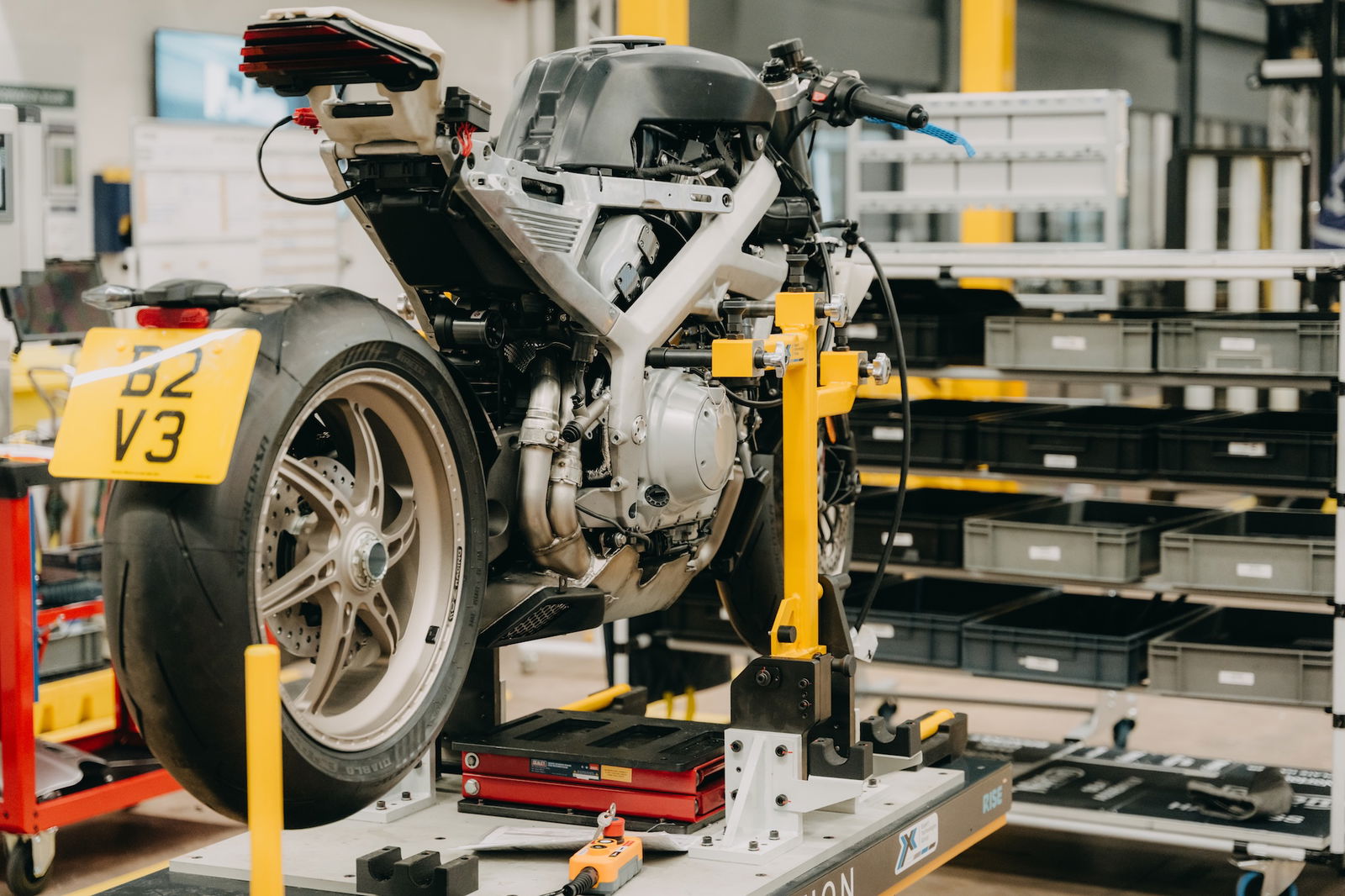

We arrive at the start of Norton’s assembly line and, from a distance, it looks like a group of build stations with bikes mounted on trolleys at different stages of the production process. It’s only as I get closer that I start to see things you’d never see on a production bike.

The small yellow Dymo labels pointing at various parts are the biggest clue. “At the moment, we’re running on prototype bikes; there’s nothing production-based running through the facility at this time. We’re hoping to get that in the next month.” The ‘that’ Simon refers to is the first batch of customer bikes, but before the factory can reach that milestone, there’s a whole raft of testing and finessing to be done.

“We’re still going through the validation process, so we’ve just done what we call Beta 3, which is our third level of prototyping. Those bikes then go through endurance testing, mileage accumulation and extremes of temperature.” Like any bike maker, Norton is planning to put its new bikes through the wringer, but to be able to do that with accuracy and faith in the results, it has to use the same materials, parts, staff, and – most importantly – processes that would be used during the customer build operation.

“Everything on those bikes is ‘production intent’, so it’s the same parts we’ll be using at production, the same tooling, and the same processes. That’s to validate all of those factors before we go into the main production process.”

Once those bikes complete all their on-road and endurance testing, they are stripped down, taken apart and examined at a microscopic level. If any issues appear, they’re investigated to identify the cause, flagging them to be rectified before a bike reaches the customer’s garage.

As for when production bikes roll off the line, Norton’s staff are being understandably coy on giving us a date. Recent history tells us that broken promises relating to production schedules do nothing for a brand’s reputation. I’m told, though, that they hope to have customer bikes being built at some point in March, although sensibly that isn’t set in stone. This is, after all, Norton’s first foray under new leadership. It’s building all-new bikes that have never been built before. Everything that has rolled out of this factory previously has existed in another Norton timeline. For the V4s and the Commandos, there had been a process, a way of doing things. There were examples to study and experience to draw from the legacy staff.

This is the new Norton building, the new Nortons. There’s a lot at stake.

The next leg of the tour takes us to something that should be ridiculously boring, but actually isn’t. I’m looking at a mobile parts tray, with containers of different sizes hanging from a backboard, each holding various nuts, bolts, fasteners and clips. To me, it looks like any other parts trolley, but like almost all the other tools in the factory, it’s actually a clever piece of connected kit designed to ensure consistency and efficiency.

“These are what we call our C-class parts – nuts and bolts and so on. It’s a two-bin system, so the same part sits in the top and bottom containers. When there are none left in the bottom bin, the worker empties the parts from the top bin into it, and a little light starts flashing, and a flag pops up. That sends a signal via Bluetooth to the controlling system and then to the stores. It’s an alert that says this part, on this trolley, in this location, needs topping up. Someone then comes along, puts stock into the top bin, resets the flag, and that resets it on the system.”

For the final leg of the tour, we transition out of the factory and into the design studio. But before we get there, we pass some reminders of what has come before. The factory is littered with pre-TVS Norton-shaped easter eggs, hinting at the legacy of the brand. A row of gleaming Commando 961s line the walkway as you enter the factory. TVS and Norton’s bosses have been understandably keen to burn the story of the Garner era, but not bury the history of Norton. The rebrand, the all-new models and the wholly new direction. They all point to the future, but to us in the factory today, the echoes of the past are still very much here.

“They'll be the last ones we are building out. The end of production was October last year, so these are the very last ones off the line. You can see the green tags [on the seat unit]. That means they've been end-of-line checked. They are literally waiting to go over [to SVA testing]. There are a few V4SVs still knocking about as well. Again, just building them out, finishing off and getting them out ready for SVA and where they need to go.”

It’s a moot point, but a fairly significant one. Those bikes are the end of the Norton V4SS/V4SV/Commando 961 as we know it. The V4SS, especially, was Norton’s apparent golden ticket to the two-wheeled top table. It was lauded as being the bike that would take Norton up against the best: Ducati, Honda, and MV Agusta. By the time the Garner-era V4 arrived, it was already past its sell-by date. It was down on power, spec, and tech – the only thing it was up on was the price. Norton was a day late and a dollar short. But we believed the hype, sucked up the headlines and thought it was the real deal.

And while it may seem weird for a member of the motorcycle press to be, once again, bigging up Norton, after so many built it up before, this time, it does feel different. Norton under Garner was a closed book. There were very few actual bike launches, and if you weren’t in his merry band of ‘mates’, you hadn’t got a hope of getting on one of his bikes for a road test. Now, though, with TVS at the helm, Norton feels much more like an open door.

The factory tour wasn’t some carefully curated session with staff briefed on where we’d be, what to say and when to say it. At some points, it genuinely felt like I was in the way as the Norton staff and building contractors went about their work.

In contrast, one of my old editors visited Donington Hall nearly a decade ago, while Mr Garner was in charge. One thing he said about his visits always always stayed with me. It was something like: “Every time I walk into the Norton factory, I always get the feeling that Stuart [Garner] has just dashed out of his office and told everyone to look busy!”

I didn’t get that impression today.

Find the latest motorcycle news on Visordown.com