Missing Link - The Story of Trick Frames

In the days when the Japanese thought a frame was just something to hang an engine from, there was a booming trick-frame market in the UK. Did we show them how it should be done?

It was the summer of 1985. Me and my Honda CBX Thou' were heading north up the M6 in a hurry. We were racing a 2.8 injection Capri and this 125-130mph duel had been going on for the previous three or four miles, but now it was no longer visible in the mirrors. It was alongside.

My six-into-one Laser pipe was screaming like a diving Fokker, black visor pressed against the massive clocks and arms locked in a ninety-degree bend - I was barely in control. The weave (which had started about three miles ago) was now so pronounced we were using the whole of the middle lane to keep it under control. And there, to my right, the Capri's passenger was reading the Telegraph as they cruised on by, oblivious to the drama.

But that's just how it was. If you wanted the latest Jap superbike of the time you couldn't expect it to handle. They were heavy (quarter of a ton, dry), the tyres were ludicrously skinny and the forks and swingarms were incapable of dealing with the weight and stresses.

Honda's mad CBX was by no means alone. Yamaha dished the flab up in the giant XS1100 package. Kawasaki kept it up for nearly 15 years, right back to the early 1970's four-piped Z900, until they finally got it right with the GPz900. Suzuki's weave and wallow merchants carried the names of the GS range, but the most over-engined, under-framed versions bore the GSX title. Wow did they handle badly. Like a pig on stilts in a crosswind.

But, at the time, they were great engines shunting out well over 100bhp with enough torque to lose a passenger off the back at the merest twitch of the throttle cables. A healthy tuning market, fostered largely by the run-what-you-brung drag market, meant even more power and with it - you guessed - even worse handling.

The Japanese just couldn't build a chassis to save their (or your) lives. Their all-conquering grasp on the motorcycle market, don't forget, was effectively little more than a decade old, and while they concentrated their talented engineering efforts on the engines and ultimate power figures, the chassis components took back stage. They probably weren't wrong - power outputs, reliability and top speed hooked the buying public. But they were also building a frustration and contradiction into their products: power and speed you couldn't use. While the Japanese continued up this path, a spontaneous movement was growing alongside - our talented chassis engineers were getting jiggy with the jigs and (inevitably) showing the Japanese the way...

In the UK alone there were more chassis experts than you could shake a wobbly, bad-handling stick at: P+M, Rickman, Exactweld, Saxon, Hejira, Tony Foale, Maxton and Hossack, to name but a few. Harris and Spondon dominated the market. On the continent firms like Egli, Moto Martin, Nico Bakker and Bimota plied their trades. All of these grew out of racing but were drawn into serving a mass-market movement of road riders wanting to banish the weaves and wobbles.

But it wasn't just these aftermarket frames that made the bikes handle. What it really allowed the special builder to do was optimise the whole chassis by selecting the finest available racing parts (like lightweight wheels and proper brakes) allied to the choice of superior rubberware and optimum chassis geometry.

For a typical example, take a look at a standard Kawasaki Z900's frame. It was the way in those days to build the headstocks really high with long front downtubes. Clearly this did not create the strongest lateral or torsional strength for the headstock and, to make matters even worse, it also means that the forks had to be longer and therefore flexier. Simple to fix if you build a frame with a lower headstock in the first place. And the way to achieve this was to build frame tubes which embraced the engine, like arms, connecting head stock to swingarm, rather than sitting the engine in vertical twin loops as per traditional frames of the time. Thus was born the perimeter frame; tubes at first, later box section alloy. It meant a stiffer headstock, shorter forks and, if you incorporate wider yokes, fatter rubber - hey presto!

People all over the world burned the midnight oil in the pursuit of handling nirvana. Some found it and showed the rest how it should be done and, despite the Japanese adopting then mass-producing ideas that may have first seen the light of day in England, a few are still in business.

HARRIS

Showing the Japanese how

Steve Harris, Lester Harris and Steve Bayford make up Hertford-based Harris Performance, a firm now employing 28 people with nearly 30 years trading experience.

The three of them went to school together, Steve and Lester doingengineering apprenticeships with two different race car chassis builders and Bayford plying a more managerial role with the Post Office.

It was racing that got them all back together. Steve Harris: "Lester and I desperately wanted to go racing, but we couldn't afford to do it in cars so we got into bikes. We were making bits for our own race bikes and people kept saying, 'oh can you do one of those for us', and it kind of went from there.

"The Japs were making great engines and shit chassis so we got into four-strokes first with the big Kawasaki engines. We had lots of success in racing and that definitely helped. Riders like Phil Read, Tony Rutter, Barry Sheene, Steve Parrish, Mick Grant, John Ekerold, John Newbold and Tom Herron all rode and won for us."

It was the success of their F1 chassis that spawned the famed Magnum road kits. Steve: "We started noticing that people were using our race stuff to build road bikes and most of them were pretty dire, so we decided to build the Magnum kit and the balloon went up."

The Magnum 2 really started the ball rolling for the firm after they got Jan Felstrom from Target Design (responsible for the Suzuki Katana) to make the clay mould for the Harris-made fibreglass bodywork. Harris sold an incredible 2000 Magnum 2 kits.

The rest, as they say, is history. Does Steve Harris think that Britain's army of specialist frame builders showed the Japanese the way? "Oh, undoubtedly yes, I think we all did. I remember at Oulton Park once I naively agreed to wheel our monocoque, beam-frame Decorite Rotax out for the Honda guys to photograph, and then saw their version of it the following season!"

But what of the future Steve? "Two wheel drive will change chassis design dramatically over the next 10 or 20 years. It's going to happen."

And any advice to anyone thinking of building a special? "People have always been putting the best engines in the best chassis. Remember the Triton? But don't underestimate the task. I'd suggest people buy a complete donor bike with all the electrics, wheels and suspension and improve the bike gradually when it's up and running as they can afford it."

Harris Performance Products (01992) 532501/www.harrisperformance.com

SPONDON

A hobby that influenced an industry

Spondon Engineering, on the outskirts of Derby, started as a partnership between Bob Stevenson and Stuart Tiller way back in 1969."Fook me, that means we've been at it for exactly 35 years," says a shocked-looking Bob.

The pair, now a limited company, had a mutual interest in engineering and racing. "As a lad in Derby," says Bob, "if you wanted an engineering apprenticeship there were only two places - Rolls Royce's or the railway. I took mine at Royce's and Stuart at the railway. We got to know each other through racing and started making bits for our race bikes, which then turned into making bits for people who liked what we did. It got to the point where we had to jack our jobs in and do it full time."

Spondon's first premises were once seen, never forgotten. Round the back of an old bookmakers shop a series of leaky and decrepit Nissen huts housed not poultry and pigeons, as you'd first suspect, but the Spondon business for the best part of 20 years. Property aside, there was no denying the quality of the produce that left the rickety buildings.

The first major line of commerce for Spondon was making chassis for the Yamaha TZ. "Those first standard 750 Yam frames were so weak around the headstock they'd just snap off," says the ace brazer and steel tube specialist.

"We used to hang the broken headstocks off the workshop walls like animal trophies." If you've ever ridden a TZ750 the irony will not be lost on you...

"We could all make better frames than the Japanese back then," says Bob, managing a sentence without 'fuck' in it for the first time that afternoon. "But they got the old learning curve out and soon caught up. In the 1970s it was easy for us to improve their bikes but as the 1980s went on it got harder and harder."

I ask Bob whether he believes companies like Spondon are partly responsible for making the Japanese take chassis development seriously. His answer, cloaked in modesty, sheds little light on the subject: "Fuck knows. Who knows? They're queer fuckers - a breed apart."

Spondon have survived this transitional period with orders from all over the world. Perennial favourites are the Suzuki Bandit 1200 motor, Blade and R1 engines.

And what's your advice to anyone building a special Bob? "It's not everyone's cup of tea for sure. You've got to be a bit handy with your hands but you've got to be even handier with your head. We watch frame kits going out of the door and we can only hope..."

Spondon are on (01332) 662157.

Today's specials scene

There was, and still is, more to the specials scene than just handling alone - otherwise no-one would still be doing it. There's nothing like building a bike from scratch and actually riding it. The satisfaction factor is immense. So too is the knowledge that what you have built is also totally unique. And when a mate rings you up and says he's 'finished' his special, you can scoff knowingly, safe in the knowledge that they're never finished - there's always something to change, improve, modify or fettle. That's half the (perverted) fun.

But it has to be said that not everyone can or should contemplate doing it. I've ridden some proper horrors in my time, actually worse than the stock Japanese bikes. You know the score... wrong spring rates, wrong ride heights, lock stops that don't, cables that foul anything that moves, not enough ground clearance, piss poor carburation, wrong rim widths, too much unsprung weight, too much steered mass, pedals and levers pointing every way but the right way. Money definitely does not buy success.

The truth of the specials building matter is that you've got to be a bit of an anally retentive, perfectionist weirdo to do a good job, spending hours and hours in the garage, on the phone and in a van ferrying bits to and fro. Chances are that your first attempt will be poor but time and experience will turn you into a better builder.

Today's special scene is a diverse bag of biscuits and there is really no such thing as the norm. But it is still kept alive by a hardcore, die-hard band of people with skinned knuckles, swarf in the cleats of their boots... and a bike perfectly suited to their needs giving them miles and miles and smiles of satisfaction.

STEVE BURNS, Daddy of modern modding

Steve Burns is a good example of the specials building breed. The end results of his hard work and attention to detail have splurted across magazines all over the world during the past two decades.Perhaps the most famous Mr Burns bike was the Spondon-framed Monster - a 1500cc big -bore turbo-charged GSX1100. With the boost wound up it would churn out an arm-stretching 250bhp. Felt quite quick, it did.

Over to you, Steve: "I always had the biggest Suzukis I could get my hands on, GS750, GS1000, GSX... then I put the Mr Turbo kit on the 1100 - it knocked out 180bhp and it was all over the show. It was hard to even point where you wanted to go. I wasn't racing or anything, but I was a pretty fast road rider and in those days everyone was just racing each other all the time. You had to keep ahead.

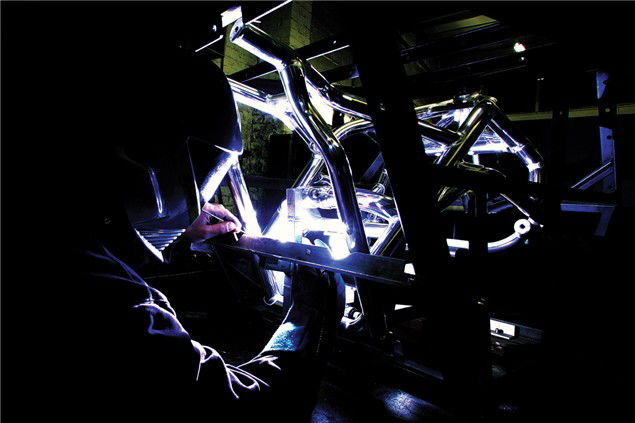

"Nico Bakker had just brought out his monoshock kit, so I wrote to him because I liked the idea of his rising rate monoshock back end but he never wrote back. Bit of a twat, really. Then I heard of the Spondon stuff and their Reynolds 531 steel frame kits. So I took the turbo engine out of the GSX and took it down to Spondon in the van."Spondon were mavericks really, they cast their own calipers, forks, yokes and discs. They experimented with all sorts like mechanical anti-dive. And they were amenable people - in it for the engineering, not the money.

"I always remember picking up my first frame from Spondon. I'd waited nearly 12 months. They'd stuck my engine in a shed with no roof, full of pigeon shit. There was swarf on the floor, no hygiene - obviously classic old school engineering shop - really old machines but every tool to do the job. It wasn't finished when I got there.

It was a Saturday afternoon, everyone else had left. He was drilling the caliper brackets by hand but must have measured them wrong. He went to bolt them on and it was out of line by one or two mil. He got hold of the caliper and threw it at the wall and it broke in two. 'Fuck, fuck, fuck,' he growls, 'I'll send you another one.' I thought 'What's happening here?' But that's just Bob."Back in those days if you wanted a fast, good-handling bike you had no alternative but to build it yourself.

"The Monster was the third incarnation of the steel frame. Bob had changed to ally and all his tooling was set up for ally. I didn't like the beam stuff - I preferred the looks of the 7020 self-annealing big tube frames. We sat in the pub and decided to copy the steel tube frame but in ally. Its looks were pretty important, no, definitely, making tubes line up with the fins, that sort of thing."It used an GSX1100EF engine with a really strong 1498cc MTC big block. It had a RayJay suck-through turbo. It did 250bhp at the rear wheel. It's only done 500 miles since I built it, ha, ha."Any advice for wannabe specials builders, Steve? "Don't bust the bank. Enjoy what you can afford and what you're capable of building. Have fun. Have a laugh."

Steve Burns is now a motorsport engineering lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire, the fifth biggest uni in the country with 35,000 students. Spot what he's up to on www.uclan.ac.uk or maybe even buy the Monster by pestering him on the e-mail at Sburns3@uclan.ac.uk

WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH

1969 Kawasaki launches insanely fast, 500cc two-stroke triple, the H1 Mach3. It handles so badly it's instantly dubbed 'The Widow-maker'. The same year, Honda launch the CB750 to a gob-smacked world audience. Four cylinders, 124mph top speed, nice styling and watch-like reliability delivered a knockout punch to the British and European bike makers. Handling? Erm, no...

1971 Suzuki spring the 'Kettle' GT750 on an unexpecting public. Weighs 524lbs

1972 Kawasaki launch 903cc dohc Z1

1974 Honda Gold Wing debuts. Yamaha's TZ700 hits the tracks

1976 Suzuki's GS750 is the hottest thing of the year

1977 XS750 hailed as one of the finest handling machines of the era. Have you ever ridden one? Yuck.

1983 Honda starts production ofV-four motors. Look out everyone...

1984 GPz900 Kawasaki sets new handling standards

1985 Yamaha FZ750/SuzukiGSX-R750 launched, both with rising rate rear monoshocks

1986 Schwantz and Rainey dominate the Transatlantic series

1987 Honda ready their greatest work to date - a crushing blow to specialist frame builders - the RC30. The tide has turned...

JOHN SCHOON'S HARRIS MAGNUM GSX-R1100

Pay attention Harris fanciers, this is the only Reynolds 531-tubed Magnum 5 in existence. The rest are made using cold-rolled steel. "The tubing was that hard the polishers and platers found it a right bastard to polish," says owner John Schoon.

John's day job is as a development engineer at Triumph in Hinckley, just down the road from his Nuneaton lair. Prior to that he worked at Harris. Are you spotting a certain air of inevitability?

The best bits look like this: bog stock GSXR1100WP motor breathing through an owner-modified Harris pipe; K&N filters and a good session on the TTS dyno to set up the fuelling (136bhp @ the rear wheel). Very sensible and quite enough for now.

The forks are 916, as is the front wheel, lavished with a whole load of anodising/nitriding and a proliferation of hlins internals. AP discs and six-pots, squeezed by a 916SP master cylinder, provide more than enough braking force.

That luvverly Harris swingarm carries a 916 axle, hub and carrier and a six-inch-wide Marchesini wheel. Yet again, Öhlins provide the boing.

But bollox to the spec. What we like about this Magnum is how it works and how it's finished. Take a sneaky peek at the handlebar switchgear and admire the way it's all routed, factory style, through the Renthal fat bars, risers and yokes so it doesn't foul, can't be seen and can be forgotten. Attention to detail, it's the fine line between munter and minter.

Yup, there are some lovely touches to this used and abused Magnum 5, like the tyres used right to the edge (I like to see that). But it's the way John rides it, how it rides like it's an extension of his body, that proves the point to me. Handcrafted in Nuneaton for the owner, by the owner. Unique. Special. Sweet. Is it for sale? Is it buggery, it's still not finished...

"Can I thank my wife Conny for all the help and support?," says John. No, course you can't. This is a rufty tufty biker's magazine. What are you thinking of?

Specials contact and info:

www.gamma498.plus.com/spondon%20engineering/

www.tzracing.btinternet.co.uk/

It was the summer of 1985. Me and my Honda CBX Thou' were heading north up the M6 in a hurry. We were racing a 2.8 injection Capri and this 125-130mph duel had been going on for the previous three or four miles, but now it was no longer visible in the mirrors. It was alongside.

My six-into-one Laser pipe was screaming like a diving Fokker, black visor pressed against the massive clocks and arms locked in a ninety-degree bend - I was barely in control. The weave (which had started about three miles ago) was now so pronounced we were using the whole of the middle lane to keep it under control. And there, to my right, the Capri's passenger was reading the Telegraph as they cruised on by, oblivious to the drama.

But that's just how it was. If you wanted the latest Jap superbike of the time you couldn't expect it to handle. They were heavy (quarter of a ton, dry), the tyres were ludicrously skinny and the forks and swingarms were incapable of dealing with the weight and stresses.

Honda's mad CBX was by no means alone. Yamaha dished the flab up in the giant XS1100 package. Kawasaki kept it up for nearly 15 years, right back to the early 1970's four-piped Z900, until they finally got it right with the GPz900. Suzuki's weave and wallow merchants carried the names of the GS range, but the most over-engined, under-framed versions bore the GSX title. Wow did they handle badly. Like a pig on stilts in a crosswind.

But, at the time, they were great engines shunting out well over 100bhp with enough torque to lose a passenger off the back at the merest twitch of the throttle cables. A healthy tuning market, fostered largely by the run-what-you-brung drag market, meant even more power and with it - you guessed - even worse handling.

The Japanese just couldn't build a chassis to save their (or your) lives. Their all-conquering grasp on the motorcycle market, don't forget, was effectively little more than a decade old, and while they concentrated their talented engineering efforts on the engines and ultimate power figures, the chassis components took back stage. They probably weren't wrong - power outputs, reliability and top speed hooked the buying public. But they were also building a frustration and contradiction into their products: power and speed you couldn't use. While the Japanese continued up this path, a spontaneous movement was growing alongside - our talented chassis engineers were getting jiggy with the jigs and (inevitably) showing the Japanese the way...

In the UK alone there were more chassis experts than you could shake a wobbly, bad-handling stick at: P+M, Rickman, Exactweld, Saxon, Hejira, Tony Foale, Maxton and Hossack, to name but a few. Harris and Spondon dominated the market. On the continent firms like Egli, Moto Martin, Nico Bakker and Bimota plied their trades. All of these grew out of racing but were drawn into serving a mass-market movement of road riders wanting to banish the weaves and wobbles.

But it wasn't just these aftermarket frames that made the bikes handle. What it really allowed the special builder to do was optimise the whole chassis by selecting the finest available racing parts (like lightweight wheels and proper brakes) allied to the choice of superior rubberware and optimum chassis geometry.

For a typical example, take a look at a standard Kawasaki Z900's frame. It was the way in those days to build the headstocks really high with long front downtubes. Clearly this did not create the strongest lateral or torsional strength for the headstock and, to make matters even worse, it also means that the forks had to be longer and therefore flexier. Simple to fix if you build a frame with a lower headstock in the first place.

And the way to achieve this was to build frame tubes which embraced the engine, like arms, connecting head stock to swingarm, rather than sitting the engine in vertical twin loops as per traditional frames of the time. Thus was born the perimeter frame; tubes at first, later box section alloy. It meant a stiffer headstock, shorter forks and, if you incorporate wider yokes, fatter rubber - hey presto!

People all over the world burned the midnight oil in the pursuit of handling nirvana. Some found it and showed the rest how it should be done and, despite the Japanese adopting then mass-producing ideas that may have first seen the light of day in England, a few are still in business.