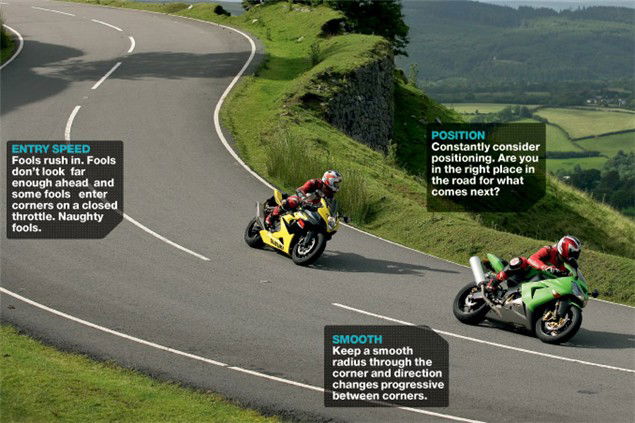

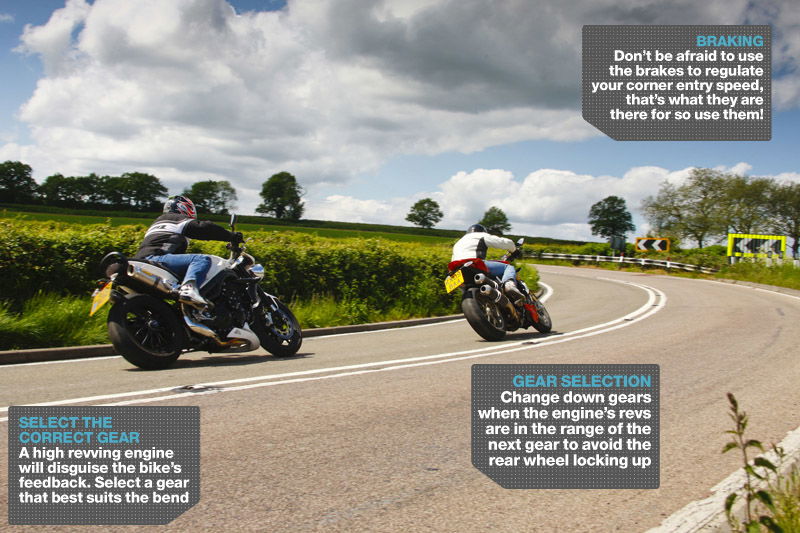

Advanced Motorcycle Riding Course: Cornering - accurate lines

There’s always more than one line through a corner, but (usually) only one is correct. A steady throttle and a settled bike make staying on the right line easier and it makes adjusting a line quicker too

Andy Morrison