Neck Braces - the future of road riding?

Go to any off-road event and 80% of the riders these days will be wearing neck braces. These items are possible life-savers, so why haven’t they been adopted by the road-riding fraternity?

height=10> | |

To understand what the human neck has to undergo in terms of stresses and strains when you ride a bike you really need to know the weight of your head. The best way to weigh your head is to cut it off and pop it onto some accurate scales. This method is fraught with difficulties. So lets speak to a mortuary technician. “An adult human head cut off around vertebra C3, with no hair, weighs somewhere between 4.5 and 5 kg, constituting around 8% of the whole body mass,” says my local mortuary technician, in between mouthfuls of egg-cress sandwich. Make that 7.0kg with a helmet and hair. That’s a good sized medicine ball perched on top of a few bits of floating bone supported by nothing more than muscle and ligaments. And while your skull and brain are neatly protected by a crash-helmet, and your upper body safe from harm with coverings of cow leather and armour, your neck is completely exposed to the elements. Should you have an impact with something hard and unyielding, what’s there to protect your neck? The answer comes in the shape of the neck brace systems currently embraced by the motocross crowd. The brace sits on your shoulders, is loosely held in place by underarm straps, and an elongated section protects the upper spine. Remarkably simple in design and yet anatomically brilliant, these carbon-fibre collars prevent the lower edges of your helmet from moving beyond certain limits, ultimately stopping you breaking your neck should you have the wrong kind of accident. That’s the theory, anyway. KNOW YOUR C-SPINESYour spine is made up of vertebrae, each one given a letter and a number. C1 (the bit that fixes your skull to your spine) to C7, the bottom vertebrae in your upper cervical spine, is a rubbish design for anything other than normal life. By normal life, we mean ‘not riding motorbikes.’ There’s a medical rhyme: “C one, two, three, four, five: keeps the diaphragm alive”. The diaphragm is the thing that assists in the filling and evacuation of your lungs. It keeps you breathing. Lose the use of that and you’re on life-support. And it just so happens that C5 is the vertebrae roughly level with the collar on your one-piece race suit. The exposed part of neck between the bottom of you helmet and your suit collar keeps you alive. Notice the use of that word again, exposed. The problem with bike accidents are the wide variety of possible accident scenarios adding extra loadings in different planes to an already vulnerable area of spine. Not only does this make the motorcyclist’s C-spine more vulnerable but by the same token it makes it much harder to protect. Speak to any paramedic or firefighter and they’ll all tell you the same. First on scene at a motorcycle accident, you must suspect C-spine injury. If the victim is unconscious you take it as read that the C-spine, and the spine in general, is injured. Car racing saw the adoption of the HANS (Head and Neck Support) system, originally designed by professor Bob Hubbard of Michigan State University for off-shore powerboat racers. Adapted and improved, the HANS system has been compulsory in F1 since 1996. Impressively, there has been no loss of life or paralysis in that sport since. So think what it could do for bikes and riders. MEET DR LEATTThe motorcycle neck brace has been pioneered by Dr Chris Leatt, a South African racer and doctor. “It started seven years ago,” says Leatt. “I was competing in an off road event and a guy crashed and broke his neck. We worked on him for ages administering CPU but it was no good. It was when they were carrying his body off the hill I thought ‘this is pointless, what a waste, there’s must be something we can do.’” The resulting research and development resulted in the Leatt Brace system. Put simply, the neck cup, worn around the shoulders with elongated sections front and back, creates new load paths for the head and helmet, diverting them away from the vulnerable C-spine. It’s use in motocross and off road riding is huge. So why the focus on off-road and not road-riding? THE LEGAL HURDLESAlpinestars have just launched their own interpretation of the neck brace. Three years in development the motocross focused neck restraint is also designed to minimize the risks of C-spine injury. Dainese’s D-Air neck protection system is already widely publicized but still undergoing research and development. It’s also an obvious area of interest for helmet manufacturers as well but, interestingly, Dr Leatt’s tightly-worded patent for the Leatt Brace may prove to be a stumbling block for further development. Arai Europe’s technical manager Willem Poelwyjk says, “we saw the Leatt system at the Autosport show and were very impressed. In motocross the rider tends to remain in the same position regardless of the type of machine they ride, while road riders could ride a sports bike one day then a cruiser style bike the next, both of which require very different protective clothing and body and neck positions. This creates obvious problems for not just safety but also legal responsibility.” Ah, legalities. Was wondering when that would crop up. And this seems to be one reason we’re not all wearing neck-braces on the road. Leatt haven’t pushed their system for road-riders (even though it works fine), preferring instead to stick with the off-road market they know. Their patent means others can’t copy their design just for road-riders. Alpinestars have circumvented this and have their system but it isn’t out yet. Yet it’s only a matter of time until the marketing hits road-riders. You’d rightly look in horror if someone donned their leathers at a trackday without slipping in a back protector and sped off with their helmet unfastened. And we’re not that far away from feeling the same way about neck protection. |

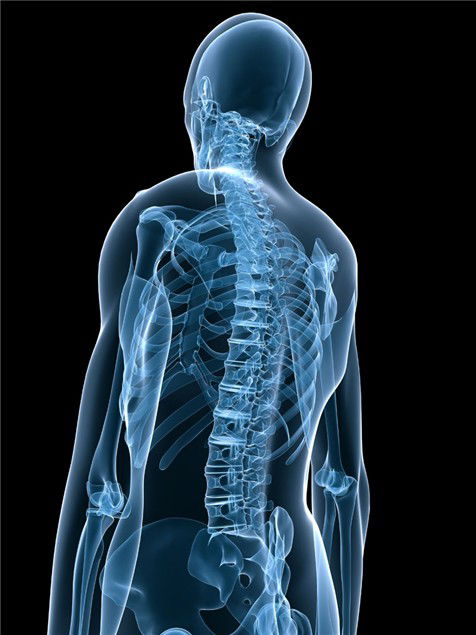

To understand what the human neck has to undergo in terms of stresses and strains when you ride a bike you really need to know the weight of your head. The best way to weigh your head is to cut it off and pop it onto some accurate scales. This method is fraught with difficulties. So lets speak to a mortuary technician. “An adult human head cut off around vertebra C3, with no hair, weighs somewhere between 4.5 and 5 kg, constituting around 8% of the whole body mass,” says my local mortuary technician, in between mouthfuls of egg-cress sandwich.

Make that 7.0kg with a helmet and hair. That’s a good sized medicine ball perched on top of a few bits of floating bone supported by nothing more than muscle and ligaments. And while your skull and brain are neatly protected by a crash-helmet, and your upper body safe from harm with coverings of cow leather and armour, your neck is completely exposed to the elements. Should you have an impact with something hard and unyielding, what’s there to protect your neck?

The answer comes in the shape of the neck brace systems currently embraced by the motocross crowd. The brace sits on your shoulders, is loosely held in place by underarm straps, and an elongated section protects the upper spine. Remarkably simple in design and yet anatomically brilliant, these carbon-fibre collars prevent the lower edges of your helmet from moving beyond certain limits, ultimately stopping you breaking your neck should you have the wrong kind of accident. That’s the theory, anyway.

Know your C-spines

Your spine is made up of vertebrae, each one given a letter and a number. C1 (the bit that fixes your skull to your spine) to C7, the bottom vertebrae in your upper cervical spine, is a rubbish design for anything other than normal life. By normal life, we mean ‘not riding motorbikes.’ There’s a medical rhyme: “C one, two, three, four, five: keeps the diaphragm alive”. The diaphragm is the thing that assists in the filling and evacuation of your lungs. It keeps you breathing. Lose the use of that and you’re on life-support.

And it just so happens that C5 is the vertebrae roughly level with the collar on your one-piece race suit. The exposed part of neck between the bottom of you helmet and your suit collar keeps you alive. Notice the use of that word again, exposed. The problem with bike accidents are the wide variety of possible accident scenarios adding extra loadings in different planes to an already vulnerable area of spine. Not only does this make the motorcyclist’s C-spine more vulnerable but by the same token it makes it much harder to protect. Speak to any paramedic or firefighter and they’ll all tell you the same. First on scene at a motorcycle accident, you must suspect C-spine injury. If the victim is unconscious you take it as read that the C-spine, and the spine in general, is injured.

Car racing saw the adoption of the HANS (Head and Neck Support) system, originally designed by professor Bob Hubbard of Michigan State University for off-shore powerboat racers. Adapted and improved, the HANS system has been compulsory in F1 since 1996. Impressively, there has been no loss of life or paralysis in that sport since. So think what it could do for bikes and riders.

Meet Dr Leatt

The motorcycle neck brace has been pioneered by Dr Chris Leatt, a South African racer and doctor. “It started seven years ago,” says Leatt. “I was competing in an off road event and a guy crashed and broke his neck. We worked on him for ages administering CPU but it was no good. It was when they were carrying his body off the hill I thought ‘this is pointless, what a waste, there’s must be something we can do.’” The resulting research and development resulted in the Leatt Brace system. Put simply, the neck cup, worn around the shoulders with elongated sections front and back, creates new load paths for the head and helmet, diverting them away from the vulnerable C-spine. It’s use in motocross and off road riding is huge. So why the focus on off-road and not road-riding?

“As a new company we had to concentrate on the areas that needed the most help first. Motocross has far more instances of cervical spine damage due to the nature of the accidents, so we started there first. But my background is really road-racing, I just off-road to keep fit. We’ve got the top three in the South African Superbike series wearing the Leatt Brace but we have to take things gradually. There’s still more development to do, especially in conjunction with the clothing and helmets used.”

The legal hurdles

Alpinestars have just launched their own interpretation of the neck brace. Three years in development the motocross focused neck restraint is also designed to minimize the risks of C-spine injury. Dainese’s D-Air neck protection system is already widely publicized but still undergoing research and development. It’s also an obvious area of interest for helmet manufacturers as well but, interestingly, Dr Leatt’s tightly-worded patent for the Leatt Brace may prove to be a stumbling block for further development.

Arai Europe’s technical manager Willem Poelwyjk says, “we saw the Leatt system at the Autosport show and were very impressed. In motocross the rider tends to remain in the same position regardless of the type of machine they ride, while road riders could ride a sports bike one day then a cruiser style bike the next, both of which require very different protective clothing and body and neck positions. This creates obvious problems for not just safety but also legal responsibility.” Ah, legalities. Was wondering when that would crop up.

And this seems to be one reason we’re not all wearing neck-braces on the road. Leatt haven’t pushed their system for road-riders (even though it works fine), preferring instead to stick with the off-road market they know. Their patent means others can’t copy their design just for road-riders. Alpinestars have circumvented this and have their system but it isn’t out yet. Yet it’s only a matter of time until the marketing hits road-riders. You’d rightly look in horror if someone donned their leathers at a trackday without slipping in a back protector and sped off with their helmet unfastened. And we’re not that far away from feeling the same way about neck protection.