Bloodlust - Honda NR750 vs. Ducati Desmosedici

Honda’s NR750 and Ducati’s Desmosedici are two of the most stunning bikes ever built. Each are worth £40,000 and both were developed from pure GP technology. There may be an incredible 16 years between them, but exclusivity this rare is timeless

It may be that puberty was confusing me at the time, but back in 1979 I could never understand why the Honda NR500 thingy was so rubbish compared to Barry Sheene’s Suzuki and Kenny Robert’s Yamaha. So it was only when I grew up a bit that I began to realize what ‘Big H’ was trying to achieve. From then on, and especially when my teen hero Freddie Spencer appeared on the GP scene, I took more interest in the progress of the NR (New Racing) 500, or ‘Never Ready.’ Freddie was flying at the 1981 British GP in 1981, but it quit and so did Honda soon afterwards. Or so I thought. Because when I signed for Honda in 1987 to ride in 500 GPs alongside Spencer, I caught a glimpse of a new NR during one of my many trips to HRC in Japan. Being the new boy, I decided to blank it from my mind and tell no one in just in case someone accidentally pushed me off Mount Fuji. As we know now, that engine was the basis of the NR750 road bike. Honda’s slightly frivolous venture into the world of oval pistons started, publicly anyway, in 1978. Returning to the GP scene Honda wanted to develop a four-stroke challenger to the two-stroke machines that were currently reigning the 500 GP class. The first NR, the NR500 0X, combined an oval-pistoned engine with a monocoque frame. By the end of its development it was reckoned that the NR produced around 130bhp and revved to over 20,000rpm, but despite all their best efforts Honda couldn’t make it competitive. In 1982 Honda relented and joined the two-stroke masses with the V3 NS500. But the NR project wasn’t dead. Not yet. In 1987 Honda entered the Le Mans Endurance race with the NR750. Weighing just 145kg the NR reputedly made 150bhp, but unfortunately failed to finish the race due to its oval pistons going gaga. Honda continued to race this bored-out NR engine wrapped in a continually improving chassis in F1 spec in the odd race around the globe. And then it was banned by the FIM. Spoilsports. We had seen the last of the NR, until 1990... In a triumphant fanfare of corporate glory Honda debuted the road going NR750 in 1990 by using the NR750 as traveling marshal’s bikes at the Suzuka 8-Hour race. Two years later the NR750 was unveiled as the ultimate road bike. Amongst other things Honda claimed this new bike was capable of topping 300kph (187mph), something it later proved with little Loris Capirossi at the helm as it set both flying mile and standing quarter records. But with only 200 made, and with a £38,000 price tag, this was not a bike for the masses. This was Honda showing the world how clever they were.The limited production run was never increased and the NR remained a one-off production run of super-exclusive machines. Compared to the NR, Ducati’s Desmosedici appeared on the race scene with far more of an impact. When, in 2002, four strokes were first allowed in MotoGP Ducati was busy developing their MotoGP bike back at Bologna, a project that had started only a year earlier. In keeping with Ducati’s image the MotoGP bike had to have a few key features, namely a tubular chassis, desmodromic valves, but it couldn’t be a twin. Twins simply wouldn’t produce enough power for MotoGP, so Ducati made a ‘super twin.’ They put two 90-degree L-twins together and made a V4. Throughout 2002 two versions of the engine were tested, one with an irregular firing order, and one where twin pairs of pistons fired together. This became known as the twin-pulse motor. Initially the twin pulse configuration was found to put too much strain on the engine’s internal components, so Ducati Corse decided they would line up on the grid in 2003 using the screamer engine underneath Troy Bayliss and Loris Capirossi. From the outset the bike was blisteringly fast. They swapped to twin pulse a year later when they solved certain reliability issues. When Ducati decided to go Moto GP racing with a four cylinder I thought they had made the worst decision ever. They had been dominant in WSB racing for 10 years but surely that was because they had an unfair capacity advantage and their special Desmodronic system. And what did they know about four cylinder engines or GP racing? It wasn’t long before I was eating humble crumble because in its first ever MotoGP the Desmo finished in third and fifth place with, fittingly, Italian Loris leading Troy home. Then, in only its sixth race at Catalunya, Loris put the Desmo on the top step of the podium, a stunning achievement. Ducati Corse’s team of engineers (whose average age was just 28) had pulled off the same feat they’d done in WSB: beaten the combined might of the Japanese. Then Ducati dropped its bombshell. World Ducati Weekend, 2004, and in front of thousands of fans, Ducati president Federico Minoli announced that there would be a limited run of road-going MotoGP bikes, called the Desmosedici RR. The Italian company was going to do what the Japanese never have the balls to - build a MotoGP replica for the road. Four years later Ducati has lived up to its promise and sold all 1,500 Desmosdici RRs. It’s not as exclusive as the NR750, but the Ducati represents the most technically-advanced road bike ever built. It is the Honda NR750 of its day. Niall Mackenzie DUCATI DESMOSEDICI RRThe first MotoGP replica with indicators and a licence plate finally hits the road in the UK... As I wasn’t able to attend the Desmosedici RR press test I have been absolutely gagging to ride this bike for months, especially as the press reports read that this machine was like no other in history sold to the public. I had also heard from some very capable riders that from the moment you hit the starter button the Desmosedici demanded respect, so the inexperienced or faint hearted should stay well away. Our bike was loaned by my friend Robert Burns (yes he is mad) and it had the full race exhaust fitted which straight away made it the loudest bike I’ve ever ridden on the road. To give you some idea just how noisy it is, a conversation next to the bike at tick over is impossible, so riding without earplugs could only ever result in permanent deafness. What’s that my love? Most noisy track days nowadays have a dB limit so I reckon owners could struggle for track time, although remember there is always Knockhill where the sheep already wear nice earmuffs! The starting and warming up procedure on the Desmo takes absolutely ages. And it’s not because this magnificent piece of engineering needs more time than a steam locomotive to get up temperature. It’s because you will be instantly transformed into Loris Capirossi’s 2006 crew chief, getting ready for your home Grand Prix. A tiny blip on the throttle and the rev counter bars instantly say 6,000rpm, it’s bloody brilliant! I kept finding myself blipping the throttle just to hear it bark. Does that make me a wrong person? It may feel smooth revving it on the stand but the engine feels rough and burbles a fair bit while picking away. First gear is quite tall, but manageable with the smooth hydraulic clutch. It reminds me of race bikes I’ve ridden in the past, especially, and unsurprisingly, the Ducati 990 MotoGP bike I rode for a few brief laps at Valencia a couple of years ago. And it sounds the same. As much as I appreciated the thundering racket I was acutely aware that most of the public I was passing while riding through the Peak District didn’t probably didn’t feel the same. On more than one occasion I saw pets and small children positively traumatized as I barked my way through the countryside, so I was short shifting for a big part of the day. Not that it seemed to help the fuel range, at just 57 miles the fuel light started blinking. I don’t suppose good miles per gallon was ever up there in the grand scheme of things when creating this machine. And nor was the dash. Apart from the 16RR welcome message, the dash looked identical to the 1098 with the same options including the downloadable data logging. I noticed there was no traction control option while flicking through the modes as per the 1098R, which I found odd. With power on tap and the technology available I thought this would have been good should it get damp but then again would anyone take their 40K toy out in the rain? One other feature missing that I feel would have completed the package would have a been quick shifter. Maybe not totally practical all of the time, but something that could be switched on and off would have been ace. Like the 990 race bike the RR is not a small machine but the low and high speed handling still feels very light. The size also gives a roomy riding position with the round race pegs set slightly back but comfortable position. You also have on board the best Öhlins suspension including stupendously expensive Gas front forks. The bike also has a specially made 16-inch rear, 17-inch front Bridgestone tyres fitted which when matched to the best suspension available gives super accurate handling on smooth roads at least. On the bumpy stuff, while never doing anything untoward, the feedback I was getting told me I needed softer springs and less damping to get things working properly. But this is a bike that was born on a track and feels confused to be on the road, like it is riding in slow motion. Stick it on a warm track and I’m sure it would be stunning. But good as the handling is the Ducati will always be dominated by one thing: it’s massively powerful engine. The L-shaped V4 is what the Desmosedici RR is all about, and you are constantly reminded you are riding no ordinary motorcycle. After the few seconds of rough take-off you then begin to feel the unusual pulsing of the motor combined with a fair bit of mechanical noise. Above 6,000rpm this disappears and begin to experience the unique on board sound that until recently has only been familiar to the likes of Bayliss and Co. The front wheel comes up but it is by no means a wheelie monster as the power is delivered rapidly but in a very linear fashion. It’s not the beast you would expect it to be, or indeed that the sound threatens it will be, but rather delivers a very fast, controllable wave of power that builds up into a crescendo, rather than screaming to a climax like an inline four. You might expect that this isn’t a bike for the faint hearted, but you’d be wrong. Apart from a few reminders such as the notchy slipper clutch feel when back shifting and the huge stopping power of monoblock radial mounted Brembos the Desmo doesn’t feel like a race bike with lights. It’s a fast, refined and very powerful bike. But isn’t that what racers want? Modern GP bikes are no longer the spit you over the top, wafer thin powerband two-strokes they used to be. Power with control is the order of the day. Spending time with this bike is a curious, but in many ways complete experience. First you enter your garage and slip off the special silk cover to reveal your immaculate machine. Then wheel her out into the daylight, hit the button and enjoy the 15 minutes of warming up before getting on board. If you happen to be at a track at this point then you will be having the full MotoGP package. A road ride will still be terrific but will also leave you frustrated. However you will be God of all Gods in the pub car park or biker meet. URRY’S VIEWWhile the NR is a master class in the subtle, the Desmo is an in-your-face blast of Italian brutality. From the moment I hit the starter and unleashed what can only be described as armageddon from the pipes, to the moment I very carefully, and with much relief, put it back in the van it was a terrifying experience. Not terrifying as in scary to ride, more the anticipation surrounding it. This is a MotoGP bike with lights, it’ll rip your arms off and use them to beat you to a pulp, won’t it? Well no, actually it won’t. I hate to say it, but the 1098R is a far more brutal bike to ride, the RR is actually a bit of a pussycat. A bloody fast one, but not the uncontrollable animal I was expecting. The riding position is comfortable (apart from the seat) with the bars splayed out quite wide and the pegs fairly low, which surprised me, and the engine doesn’t spend its life trying to smash the clocks into your face, it’s tractable, strong and not a wheelie beast at all. But unlike the NR the Desmo sounds and feels like a race bike. The engine rattles from its dry clutch, roars through the open pipe and pops and bangs on over-run, something the NR would never consider doing, that would be rude. The Ducati is alive, wild and full of Italian spirit and passion. But the NR feels, and I reckon looks, more special, even though it is 16-years older. Jon Urry Living With The Desmo: Steve MooreSteve has owned his for two months and lives in Winchester DESMO TECHMake no mistake, this is about as close as you can get to a 990 MotoGP bike for public use. According to Ducati the RR shares many components with the GP6 race bike. The 989cc L-shaped V4 engine has the same bore and stroke (82mm x 42.56mm) as the GP bike as well as the twin-pulse firing order and, of course, desmodromic valve train. The engine’s cases and cylinders are made of sand-cast aluminium while the cam and alternator are sand-cast magnesium and the sump and clutch covers are made out of pressed magnesium alloy, all of which increase the motor’s strength while reducing its weight. Unlike Ducati V-twins the Desmo has gear driven cams, rather than belt driven. The frame is constructed from tubular steel and has exactly the same geometry as the GP6 bike and uses the engine as a stressed member. The swingarm is also identical to the race bike geometry-wise and has its shock mounted to a rocker which is hinged to the crank case. Keeping with the race bike link the Desmo has a 16-inch rear wheel, rather than the conventional road bike 17-inch. This has meant that Bridgestone has had to develop a unique tyre for the bike, which will set you back around £240 alone. The front wheel is a more traditional 17-inch item and both use the same 7-spoke design as the GP6. As you would expect suspension is Öhlins with the forks using a gas-pressurised system, a first for road bikes but common on racers. Well racers in the MotoGP paddock anyway. All the bodywork is carbon fibre but Ducati had to approach the Ferrari F1 team to construct a ceramic carbon fibre cover around the exhaust’s exits due to the intense heat. HONDA NR 750The NR 750 couldn’t be a more different animal to the Desmosedici. It may have been developed from the same raw racetrack background but Honda’s intention at the time was never to build some beast that only the experienced rider could enjoy riding. People assumed it would be an animal, but it was simply a technical tour de force. And while they might have scared most off with the £38,000 price tag in 1992, the NR today is as easy to ride as a CG125. Just a bit more costly should you drop it! Its low seat height and VFR riding position means it fits everybody and it’s no surprise the footrests, handlebars and levers are all in just the right place for a comfortable ride. Very Honda and totally unlike modern day sportsbikes which are adopting the compact, jockey riding position. Despite it being 16 years from the launch in the summer sun the NR is still jaw droppingly beautiful. Its looks are timeless and this is underlined when you notice the many styling similarities shared by both the Desmo and the NR: the lights, belly pan, underseat exhausts and ducts to name a few. In fact when the designer of the 916, Massimo Tamburini, saw the NR he was so inspired he redesigned several of the key features of the Ducati. Given that this was in 1992, who could blame him? Even starting the NR is a special occasion. The nickel silver and carbon fibre ignition key trumps the Desmo’s regular item and then when you slot it home and click it clockwise your are treated lots of whirring and needles moving while the holographic digital speedo and trip counter comes to life. The white tacho in the centre still looks modern, the other dials more Ford Escort. Next it’s time to hit the starter button that brings the 32-valve motor gently to life with no more fuss or noise than the average Nissan Micra. Rev her up however and you get the best throaty engine note ever. Considering the amount of parts rattling around inside there is virtually no mechanical clatter, just the gruff sound of induction and exhaust. Pulling away the hydraulic clutch is light, which compliments the slick-shifting gearbox that has close ratios but seem well suited for road riding. In fact for the first few feet you would be forgiven for thinking you might be riding a VFR, but that is where the similarity ends. The engine note first becomes deeper, but as the revs build past 10,000rpm and on towards the 15,000 red line you get a much cleaner sound. The most unusual part during all of this is the power band feels totally linear from 2,000rpm to 15,000rpm with no surges or dips. With this bike being built originally to compete with GP two strokes that peaked at around 12,000rpm HRC were focusing on revs as opposed to torque to find an advantage. This is a bike that likes to be revved and although it may be an exotic technical marvel, being a Honda you just know nothing will ever break no matter how much abuse you dish out. It is light years from feeling like a VFR, but if you’ve ever ridden an RC30 or RC45 (the NR is actually an RC40) the NR is similar but smoother and more refined. Back in 1992 multi adjustable suspension and the 43mm USD forks were relatively new so the best available from Japan was fitted to the NR, which still holds up. With the centre of gravity being low the side-to-side steering is quite heavy on the NR, however general stability is fine. Riding the NR is a calming experience, it’s very comfy and copes well over bumps, which suggests the suspension is on the soft side. One thing I would change on the NR I would make it taller. Being low makes it look squat and fat, plus jacking everything a few mm would go a long way livening up the handling.For me the great shame is the overall weight when it could have been so easily 40kg lighter. At over 220kg the 125bhp engine toils to deliver modern day CBR600RR performance. In a lightweight chassis it would really come to life, but I suppose that’s why the NR500 was banned from racing, as what we really have is a miniature V8 in disguise. Still if it hadn’t been banned we may never have had the NR750 road bike. Every cloud has a silver lining! URRY’S VIEWRiding the NR was even scarier than the Desmo, mainly because Niall was within punching distance should I accidentally drop it, but also because it’s so rare. I have only ever seen two before, and both were in museums so I knew riding one would be a one-off experience. But what an experience. The NR isn’t fast, but that doesn’t matter, everything about it is so special. The riding position is comfortable and relaxed and the engine sounds, well: just sounds unbelievable. It’s like a really flat VFR, but not flat as in lacking power, flat as in deep and menacing. The power delivery is beautifully smooth, huge amounts of pull from everywhere, and the sound gets even better the higher it revs. The handling wasn’t fantastic, something to do with having 16 year old OE Avon tyres fitted, and the front felt particularly vague, but I can forgive it that, it’s an old bike and in its day it must have been mind-blowing. If a bit lardy. But what really sealed the deal for me was the dash, the digital speedo is simply fantastic. For Honda to bother investing so heavily in developing a new speedo simply for one bike makes me smile. The NR is a small bubble of 1990s perfection, and I’m so glad I didn’t burst that bubble. If I could afford one I would, no question at all. Will I be able to? Not a hope in hell! Jon Urry Living With The NR750: Niall MackenzieMacca bought his NR in 1995 for less than £20,000... HONDA TECHThe NR750’s standout technical feature is its oval piston engine. Shaped like sardine cans each piston in the V4 motor has 8 valves, four for exhaust and four for intake, as well as two con-rods. This increased number of valves improves air flow into the cylinder while the oval shape is 30% smaller than a comparable pair of round pistons, meaning the engine can have a much shorter stroke while remaining compact. This shorter stroke, and titanium con rods, allows the NR to rev to 15,000rpm, which in 1992 was staggering. Very clever as it effectively made it a V8, but also horrifically complicated to manufacture. As the pistons expanded with heat, their shape was incredibly difficult to control. Honda had to develop a host of new techniques to produce the NR. A lot of components in the NR’s engine are doubled up for greater efficiency. It runs two sparkplugs per cylinder as well as two fuel injectors and two throttle bores. Each oval piston cylinder is basically two round piston ones with the gap between then removed. Then there’s the chassis. The NR’s engine is used as a stressed member, like all modern sportsbikes, and is made from extruded aluminium joined to cast headstock and swingarm areas. Again, like modern sportsbikes. It’s just that the NR did it 16 years ago! It also came with inverted forks, magnesium wheels, four-piston callipers and fully floating brake discs. Then there is the dash. In 1992 this was jaw-dropping. The LCD speedo, housed in a carbon dash, is ‘floating.’ A mirror reflects the image onto the display giving it a sense of depth so that the rider’s eyes don’t have to adjust to read the display. The final touches are carbon fibre bodywork and a special nickel silver key that is inlayed with carbon fibre resin displaying the bike’s logo. Trick beyond comparison. The only let-down? The oft-touted ‘carbon’ bodywork was nothing more than heavy fibreglass. We know because we were there in 1995 when this very bike was crashed... Where can I buy one?Hahahahaa! Hold on, let me catch my breath. Only 200 NR750s were ever made, and from what we know only three are in the UK. One is in Honda UK’s reception, one is in Niall’s garage, and we hear the other is in Ireland. They do pop up in auctions from time to time but are very rare and if you have your heart set on one then the chances are you will have to buy one abroad and import it to the UK. The best advice is to keep an eye on the specialist Auction Houses’ websites and be prepared to part with around £40,000. Getting a Desmosedici should be considerably easier, after all 1,500 have been made. Unfortunately they have all been sold for the £40,000 asking price and no more will be made according to Ducati. There are 174 Desmos scheduled for the UK and between 20 and 30 have already arrived. A few are popping up for sale, and if you try, and are prepared to pay over the odds, you should be able to get your hands on one for around £45-50,000. Try contacting you local Ducati dealer and ask around.

| |||||

It may be that puberty was confusing me at the time, but back in 1979 I could never understand why the Honda NR500 thingy was so rubbish compared to Barry Sheene’s Suzuki and Kenny Robert’s Yamaha. So it was only when I grew up a bit that I began to realize what ‘Big H’ was trying to achieve. From then on, and especially when my teen hero Freddie Spencer appeared on the GP scene, I took more interest in the progress of the NR (New Racing) 500, or ‘Never Ready.’ Freddie was flying at the 1981 British GP in 1981, but it quit and so did Honda soon afterwards. Or so I thought. Because when I signed for Honda in 1987 to ride in 500 GPs alongside Spencer, I caught a glimpse of a new NR during one of my many trips to HRC in Japan. Being the new boy, I decided to blank it from my mind and tell no one in just in case someone accidentally pushed me off Mount Fuji. As we know now, that engine was the basis of the NR750 road bike.

Honda’s slightly frivolous venture into the world of oval pistons started, publicly anyway, in 1978. Returning to the GP scene Honda wanted to develop a four-stroke challenger to the two-stroke machines that were currently reigning the 500 GP class. The first NR, the NR500 0X, combined an oval-pistoned engine with a monocoque frame. By the end of its development it was reckoned that the NR produced around 130bhp and revved to over 20,000rpm, but despite all their best efforts Honda couldn’t make it competitive. In 1982 Honda relented and joined the two-stroke masses with the V3 NS500. But the NR project wasn’t dead. Not yet.

In 1987 Honda entered the Le Mans Endurance race with the NR750. Weighing just 145kg the NR reputedly made 150bhp, but unfortunately failed to finish the race due to its oval pistons going gaga. Honda continued to race this bored-out NR engine wrapped in a continually improving chassis in F1 spec in the odd race around the globe. And then it was banned by the FIM. Spoilsports. We had seen the last of the NR, until 1990...

In a triumphant fanfare of corporate glory Honda debuted the road going NR750 in 1990 by using the NR750 as traveling marshal’s bikes at the Suzuka 8-Hour race. Two years later the NR750 was unveiled as the ultimate road bike. Amongst other things Honda claimed this new bike was capable of topping 300kph (187mph), something it later proved with little Loris Capirossi at the helm as it set both flying mile and standing quarter records. But with only 200 made, and with a £38,000 price tag, this was not a bike for the masses. This was Honda showing the world how clever they were.The limited production run was never increased and the NR remained a one-off production run of super-exclusive machines.

Compared to the NR, Ducati’s Desmosedici appeared on the race scene with far more of an impact. When, in 2002, four strokes were first allowed in MotoGP Ducati was busy developing their MotoGP bike back at Bologna, a project that had started only a year earlier. In keeping with Ducati’s image the MotoGP bike had to have a few key features, namely a tubular chassis, desmodromic valves, but it couldn’t be a twin. Twins simply wouldn’t produce enough power for MotoGP, so Ducati made a ‘super twin.’ They put two 90-degree L-twins together and made a V4.

Throughout 2002 two versions of the engine were tested, one with an irregular firing order, and one where twin pairs of pistons fired together. This became known as the twin-pulse motor. Initially the twin pulse configuration was found to put too much strain on the engine’s internal components, so Ducati Corse decided they would line up on the grid in 2003 using the screamer engine underneath Troy Bayliss and Loris Capirossi. From the outset the bike was blisteringly fast. They swapped to twin pulse a year later when they solved certain reliability issues.

When Ducati decided to go Moto GP racing with a four cylinder I thought they had made the worst decision ever. They had been dominant in WSB racing for 10 years but surely that was because they had an unfair capacity advantage and their special Desmodronic system. And what did they know about four cylinder engines or GP racing? It wasn’t long before I was eating humble crumble because in its first ever MotoGP the Desmo finished in third and fifth place with, fittingly, Italian Loris leading Troy home. Then, in only its sixth race at Catalunya, Loris put the Desmo on the top step of the podium, a stunning achievement. Ducati Corse’s team of engineers (whose average age was just 28) had pulled off the same feat they’d done in WSB: beaten the combined might of the Japanese. Then Ducati dropped its bombshell.

World Ducati Weekend, 2004, and in front of thousands of fans, Ducati president Federico Minoli announced that there would be a limited run of road-going MotoGP bikes, called the Desmosedici RR. The Italian company was going to do what the Japanese never have the balls to - build a MotoGP replica for the road. Four years later Ducati has lived up to its promise and sold all 1,500 Desmosdici RRs. It’s not as exclusive as the NR750, but the Ducati represents the most technically-advanced road bike ever built. It is the Honda NR750 of its day. - Niall Mackenzie

MODEL SPECS

DUCATI DESMOSEDICI RR

PRICE: £40,000

ENGINE: 989cc, liquid-cooled, 16-valve V-four

POWER: 200bhp @ 13,800rpm

TORQUE: 85 lb.ft @ 10,500rpm

FRONT SUSPENSION: 43mm Öhlins FG353P fully adjustable pressurised

REAR SUSPENSION: Öhlins monoshock, fully adjustable

FRONT BRAKE: 330mm disc, four-piston calipers

REAR BRAKE: 240mm disc, two-piston caliper

DRY WEIGHT: 171kg (claimed)

SEAT HEIGHT: 830mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 15l

TOP SPEED: 188mph

COLOURS: Red

HONDA NR750

PRICE: £40,000

ENGINE: 747cc, liquid-cooled, 32-valve V-four

POWER: 117bhp @ 13,500rpm

TORQUE: 47 lb.ft @ 10,000rpm

FRONT SUSPENSION: fully adjustable

SUSPENSION: monoshock, fully adjustable

FRONT BRAKE: 310mm disc, four-piston calipers

REAR BRAKE: 220mm disc, two-piston caliper

DRY WEIGHT: 223kg (claimed)

SEAT HEIGHT: 787mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 17l

TOP SPEED: 159.9mph

COLOURS: Red

Ducati Desmosedici RR Review

DUCATI DESMOSEDICI RR

The first MotoGP replica with indicators and a licence plate finally hits the road in the UK...

As I wasn’t able to attend the Desmosedici RR press test I have been absolutely gagging to ride this bike for months, especially as the press reports read that this machine was like no other in history sold to the public. I had also heard from some very capable riders that from the moment you hit the starter button the Desmosedici demanded respect, so the inexperienced or faint hearted should stay well away.

Our bike was loaned by my friend Robert Burns (yes he is mad) and it had the full race exhaust fitted which straight away made it the loudest bike I’ve ever ridden on the road. To give you some idea just how noisy it is, a conversation next to the bike at tick over is impossible, so riding without earplugs could only ever result in permanent deafness. What’s that my love? Most noisy track days nowadays have a dB limit so I reckon owners could struggle for track time, although remember there is always Knockhill where the sheep already wear nice earmuffs!

The starting and warming up procedure on the Desmo takes absolutely ages. And it’s not because this magnificent piece of engineering needs more time than a steam locomotive to get up temperature. It’s because you will be instantly transformed into Loris Capirossi’s 2006 crew chief, getting ready for your home Grand Prix. A tiny blip on the throttle and the rev counter bars instantly say 6,000rpm, it’s bloody brilliant! I kept finding myself blipping the throttle just to hear it bark. Does that make me a wrong person?

It may feel smooth revving it on the stand but the engine feels rough and burbles a fair bit while picking away. First gear is quite tall, but manageable with the smooth hydraulic clutch. It reminds me of race bikes I’ve ridden in the past, especially, and unsurprisingly, the Ducati 990 MotoGP bike I rode for a few brief laps at Valencia a couple of years ago. And it sounds the same.

As much as I appreciated the thundering racket I was acutely aware that most of the public I was passing while riding through the Peak District didn’t probably didn’t feel the same. On more than one occasion I saw pets and small children positively traumatized as I barked my way through the countryside, so I was short shifting for a big part of the day. Not that it seemed to help the fuel range, at just 57 miles the fuel light started blinking. I don’t suppose good miles per gallon was ever up there in the grand scheme of things when creating this machine. And nor was the dash.

Apart from the 16RR welcome message, the dash looked identical to the 1098 with the same options including the downloadable data logging. I noticed there was no traction control option while flicking through the modes as per the 1098R, which I found odd. With power on tap and the technology available I thought this would have been good should it get damp but then again would anyone take their 40K toy out in the rain? One other feature missing that I feel would have completed the package would have a been quick shifter. Maybe not totally practical all of the time, but something that could be switched on and off would have been ace.

Like the 990 race bike the RR is not a small machine but the low and high speed handling still feels very light. The size also gives a roomy riding position with the round race pegs set slightly back but comfortable position. You also have on board the best Öhlins suspension including stupendously expensive Gas front forks. The bike also has a specially made 16-inch rear, 17-inch front Bridgestone tyres fitted which when matched to the best suspension available gives super accurate handling on smooth roads at least. On the bumpy stuff, while never doing anything untoward, the feedback I was getting told me I needed softer springs and less damping to get things working properly. But this is a bike that was born on a track and feels confused to be on the road, like it is riding in slow motion. Stick it on a warm track and I’m sure it would be stunning. But good as the handling is the Ducati will always be dominated by one thing: it’s massively powerful engine.

The L-shaped V4 is what the Desmosedici RR is all about, and you are constantly reminded you are riding no ordinary motorcycle. After the few seconds of rough take-off you then begin to feel the unusual pulsing of the motor combined with a fair bit of mechanical noise. Above 6,000rpm this disappears and begin to experience the unique on board sound that until recently has only been familiar to the likes of Bayliss and Co. The front wheel comes up but it is by no means a wheelie monster as the power is delivered rapidly but in a very linear fashion. It’s not the beast you would expect it to be, or indeed that the sound threatens it will be, but rather delivers a very fast, controllable wave of power that builds up into a crescendo, rather than screaming to a climax like an inline four. You might expect that this isn’t a bike for the faint hearted, but you’d be wrong. Apart from a few reminders such as the notchy slipper clutch feel when back shifting and the huge stopping power of monoblock radial mounted Brembos the Desmo doesn’t feel like a race bike with lights. It’s a fast, refined and very powerful bike. But isn’t that what racers want? Modern GP bikes are no longer the spit you over the top, wafer thin powerband two-strokes they used to be. Power with control is the order of the day.

Spending time with this bike is a curious, but in many ways complete experience. First you enter your garage and slip off the special silk cover to reveal your immaculate machine. Then wheel her out into the daylight, hit the button and enjoy the 15 minutes of warming up before getting on board. If you happen to be at a track at this point then you will be having the full MotoGP package. A road ride will still be terrific but will also leave you frustrated. However you will be God of all Gods in the pub car park or biker meet.

URRY’S VIEW

While the NR is a master class in the subtle, the Desmo is an in-your-face blast of Italian brutality. From the moment I hit the starter and unleashed what can only be described as armageddon from the pipes, to the moment I very carefully, and with much relief, put it back in the van it was a terrifying experience. Not terrifying as in scary to ride, more the anticipation surrounding it. This is a MotoGP bike with lights, it’ll rip your arms off and use them to beat you to a pulp, won’t it? Well no, actually it won’t. I hate to say it, but the 1098R is a far more brutal bike to ride, the RR is actually a bit of a pussycat. A bloody fast one, but not the uncontrollable animal I was expecting. The riding position is comfortable (apart from the seat) with the bars splayed out quite wide and the pegs fairly low, which surprised me, and the engine doesn’t spend its life trying to smash the clocks into your face, it’s tractable, strong and not a wheelie beast at all. But unlike the NR the Desmo sounds and feels like a race bike. The engine rattles from its dry clutch, roars through the open pipe and pops and bangs on over-run, something the NR would never consider doing, that would be rude. The Ducati is alive, wild and full of Italian spirit and passion. But the NR feels, and I reckon looks, more special, even though it is 16-years older. Jon Urry

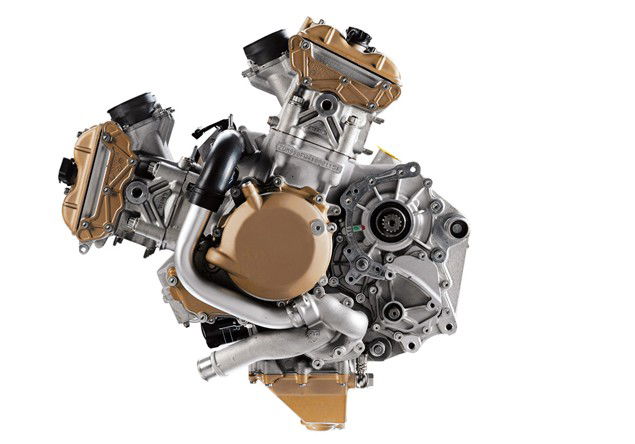

DESMO TECH

Make no mistake, this is about as close as you can get to a 990 MotoGP bike for public use. According to Ducati the RR shares many components with the GP6 race bike.

The 989cc L-shaped V4 engine has the same bore and stroke (82mm x 42.56mm) as the GP bike as well as the twin-pulse firing order and, of course, desmodromic valve train. The engine’s cases and cylinders are made of sand-cast aluminium while the cam and alternator are sand-cast magnesium and the sump and clutch covers are made out of pressed magnesium alloy, all of which increase the motor’s strength while reducing its weight. Unlike Ducati V-twins the Desmo has gear driven cams, rather than belt driven.

The frame is constructed from tubular steel and has exactly the same geometry as the GP6 bike and uses the engine as a stressed member. The swingarm is also identical to the race bike geometry-wise and has its shock mounted to a rocker which is hinged to the crank case.

Keeping with the race bike link the Desmo has a 16-inch rear wheel, rather than the conventional road bike 17-inch. This has meant that Bridgestone has had to develop a unique tyre for the bike, which will set you back around £240 alone. The front wheel is a more traditional 17-inch item and both use the same 7-spoke design as the GP6. As you would expect suspension is Öhlins with the forks using a gas-pressurised system, a first for road bikes but common on racers. Well racers in the MotoGP paddock anyway.

All the bodywork is carbon fibre but Ducati had to approach the Ferrari F1 team to construct a ceramic carbon fibre cover around the exhaust’s exits due to the intense heat.

Living With The Desmo: Steve Moore

Steve has owned his for two months and lives in Winchester

“There is a lot of mystique built up around the Desmo, but at the end of the day it’s only a motorcycle. I use mine to commute to work on, which really upsets some people. They get offended that I’m taking it out in the rain, or on trackdays, but what’s the point in having a bike and not riding it? When I wake up I look forward to riding my MotoGP replica to work. It’s not actually that radical, I reckon a 1098 is more aggressive. I’ve put the race system on my bike so it’s pretty loud, but I don’t mind the attention, it’s like having a supermodel girlfriend, you want people to look. If I could afford a Ferrari I’d drive that to work too. There is a bit of a misconception about the Desmo, people think it will go up in value, it will be an investment, but I think those people are wrong. The best way to make money out of owning a Desmo is to ride it. The first three year’s servicing on the Desmo is free, use the bike and get Ducati to pay the costs. If you reach 7,000 miles then you save the £650 service bill, which I intend to do. All it is costing me is fuel and tyres.”

Honda NR750 Review

HONDA NR 750

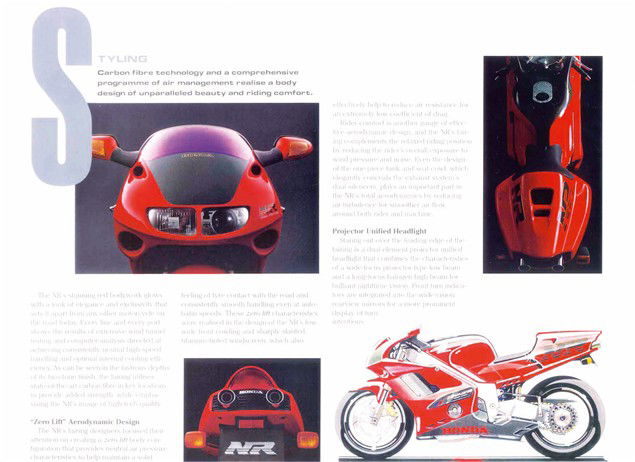

The NR 750 couldn’t be a more different animal to the Desmosedici. It may have been developed from the same raw racetrack background but Honda’s intention at the time was never to build some beast that only the experienced rider could enjoy riding. People assumed it would be an animal, but it was simply a technical tour de force. And while they might have scared most off with the £38,000 price tag in 1992, the NR today is as easy to ride as a CG125. Just a bit more costly should you drop it!

Its low seat height and VFR riding position means it fits everybody and it’s no surprise the footrests, handlebars and levers are all in just the right place for a comfortable ride. Very Honda and totally unlike modern day sportsbikes which are adopting the compact, jockey riding position.

Despite it being 16 years from the launch in the summer sun the NR is still jaw droppingly beautiful. Its looks are timeless and this is underlined when you notice the many styling similarities shared by both the Desmo and the NR: the lights, belly pan, underseat exhausts and ducts to name a few. In fact when the designer of the 916, Massimo Tamburini, saw the NR he was so inspired he redesigned several of the key features of the Ducati. Given that this was in 1992, who could blame him?

Even starting the NR is a special occasion. The nickel silver and carbon fibre ignition key trumps the Desmo’s regular item and then when you slot it home and click it clockwise your are treated lots of whirring and needles moving while the holographic digital speedo and trip counter comes to life. The white tacho in the centre still looks modern, the other dials more Ford Escort. Next it’s time to hit the starter button that brings the 32-valve motor gently to life with no more fuss or noise than the average Nissan Micra. Rev her up however and you get the best throaty engine note ever. Considering the amount of parts rattling around inside there is virtually no mechanical clatter, just the gruff sound of induction and exhaust.

Pulling away the hydraulic clutch is light, which compliments the slick-shifting gearbox that has close ratios but seem well suited for road riding. In fact for the first few feet you would be forgiven for thinking you might be riding a VFR, but that is where the similarity ends. The engine note first becomes deeper, but as the revs build past 10,000rpm and on towards the 15,000 red line you get a much cleaner sound. The most unusual part during all of this is the power band feels totally linear from 2,000rpm to 15,000rpm with no surges or dips. With this bike being built originally to compete with GP two strokes that peaked at around 12,000rpm HRC were focusing on revs as opposed to torque to find an advantage. This is a bike that likes to be revved and although it may be an exotic technical marvel, being a Honda you just know nothing will ever break no matter how much abuse you dish out.

It is light years from feeling like a VFR, but if you’ve ever ridden an RC30 or RC45 (the NR is actually an RC40) the NR is similar but smoother and more refined. Back in 1992 multi adjustable suspension and the 43mm USD forks were relatively new so the best available from Japan was fitted to the NR, which still holds up. With the centre of gravity being low the side-to-side steering is quite heavy on the NR, however general stability is fine.

Riding the NR is a calming experience, it’s very comfy and copes well over bumps, which suggests the suspension is on the soft side. One thing I would change on the NR I would make it taller. Being low makes it look squat and fat, plus jacking everything a few mm would go a long way livening up the handling.For me the great shame is the overall weight when it could have been so easily 40kg lighter. At over 220kg the 125bhp engine toils to deliver modern day CBR600RR performance. In a lightweight chassis it would really come to life, but I suppose that’s why the NR500 was banned from racing, as what we really have is a miniature V8 in disguise. Still if it hadn’t been banned we may never have had the NR750 road bike. Every cloud has a silver lining!

URRY’S VIEW

Riding the NR was even scarier than the Desmo, mainly because Niall was within punching distance should I accidentally drop it, but also because it’s so rare. I have only ever seen two before, and both were in museums so I knew riding one would be a one-off experience. But what an experience. The NR isn’t fast, but that doesn’t matter, everything about it is so special. The riding position is comfortable and relaxed and the engine sounds, well: just sounds unbelievable. It’s like a really flat VFR, but not flat as in lacking power, flat as in deep and menacing. The power delivery is beautifully smooth, huge amounts of pull from everywhere, and the sound gets even better the higher it revs. The handling wasn’t fantastic, something to do with having 16 year old OE Avon tyres fitted, and the front felt particularly vague, but I can forgive it that, it’s an old bike and in its day it must have been mind-blowing. If a bit lardy. But what really sealed the deal for me was the dash, the digital speedo is simply fantastic. For Honda to bother investing so heavily in developing a new speedo simply for one bike makes me smile. The NR is a small bubble of 1990s perfection, and I’m so glad I didn’t burst that bubble. If I could afford one I would, no question at all. Will I be able to? Not a hope in hell! Jon Urry

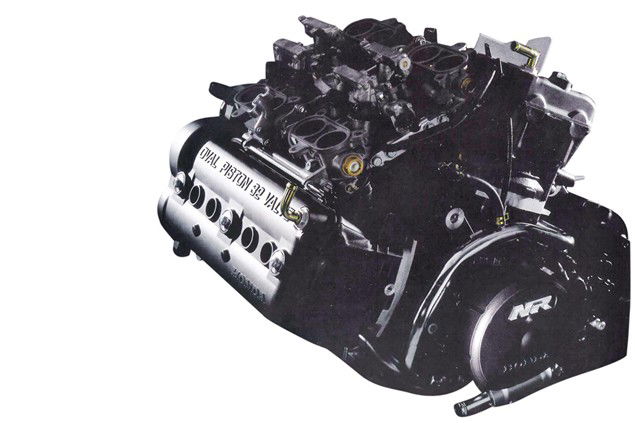

HONDA TECH

The NR750’s standout technical feature is its oval piston engine. Shaped like sardine cans each piston in the V4 motor has 8 valves, four for exhaust and four for intake, as well as two con-rods. This increased number of valves improves air flow into the cylinder while the oval shape is 30% smaller than a comparable pair of round pistons, meaning the engine can have a much shorter stroke while remaining compact. This shorter stroke, and titanium con rods, allows the NR to rev to 15,000rpm, which in 1992 was staggering. Very clever as it effectively made it a V8, but also horrifically complicated to manufacture. As the pistons expanded with heat, their shape was incredibly difficult to control. Honda had to develop a host of new techniques to produce the NR.

A lot of components in the NR’s engine are doubled up for greater efficiency. It runs two sparkplugs per cylinder as well as two fuel injectors and two throttle bores. Each oval piston cylinder is basically two round piston ones with the gap between then removed. Then there’s the chassis.

The NR’s engine is used as a stressed member, like all modern sportsbikes, and is made from extruded aluminium joined to cast headstock and swingarm areas. Again, like modern sportsbikes. It’s just that the NR did it 16 years ago! It also came with inverted forks, magnesium wheels, four-piston callipers and fully floating brake discs.

Then there is the dash. In 1992 this was jaw-dropping. The LCD speedo, housed in a carbon dash, is ‘floating.’ A mirror reflects the image onto the display giving it a sense of depth so that the rider’s eyes don’t have to adjust to read the display.

The final touches are carbon fibre bodywork and a special nickel silver key that is inlayed with carbon fibre resin displaying the bike’s logo. Trick beyond comparison. The only let-down? The oft-touted ‘carbon’ bodywork was nothing more than heavy fibreglass. We know because we were there in 1995 when this very bike was crashed...

Where can I buy one?

Hahahahaa! Hold on, let me catch my breath. Only 200 NR750s were ever made, and from what we know only three are in the UK. One is in Honda UK’s reception, one is in Niall’s garage, and we hear the other is in Ireland. They do pop up in auctions from time to time but are very rare and if you have your heart set on one then the chances are you will have to buy one abroad and import it to the UK. The best advice is to keep an eye on the specialist Auction Houses’ websites and be prepared to part with around £40,000.

Getting a Desmosedici should be considerably easier, after all 1,500 have been made. Unfortunately they have all been sold for the £40,000 asking price and no more will be made according to Ducati. There are 174 Desmos scheduled for the UK and between 20 and 30 have already arrived. A few are popping up for sale, and if you try, and are prepared to pay over the odds, you should be able to get your hands on one for around £45-50,000. Try contacting you local Ducati dealer and ask around.

Living With The NR750: Niall Mackenzie

Macca bought his NR in 1995 for less than £20,000...

“The NR is a beautiful bike to own, and typical Honda. It’s so easy and costs virtually nothing to run. Like any Honda its engine is mechanically perfect and all you have to do is stick a bit of charge in the battery, fuel in the tank and hit the starter. Mine has only got about 5,000 miles on the clock, so it hasn’t had a major service, but the oil filter is an over the counter job, the same as the RC45. I have heard that only one man in the UK can adjust the valves, but that service is a way off so I’m not too worried that yet. The tyres sizes are the same as ’92 FireBlade and every other consumable is easy to come by, I even have a spare fairing in my loft. It came with the bike, which I bought in 1995 off Steve James, the snooker champion. He was a bike nut and bought the NR when his career was on the up, but then he hit hard times, fell off the bike and I bought it off him for a good price. To ride the NR is smooth, comfortable and unassuming. I’ve taken it on track at Donington and Knockhill and I love people’s reaction, so many times I hear ‘I’ve never seen one of those before…’”