The 10 Biggest Biking Blunders

Every now and then we all drop a clanger. But for some the effects are more acute than just a red face. Here is the definitive list of biking’s biggest blunders

Sorry, who are you again?

In May 2003 KTM were approached by a TV production company called Elixir Films blathering on about how they had two actors (well one actor and his posh mate) who wanted to ride around the world on motorbikes. Could KTM supply two 950 Adventures and all the necessary backup to support the trip? KTM weren’t convinced by the pitch and chose not to get involved, deciding that they simply didn’t have the infrastructure to help out with such an ambitious project, so the production company approached BMW instead.

The two actors, as you will have guessed, were Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman. The TV series about their journey, The Long Way Round, became a global smash hit, a marketing dream and subsequently had enormous impact on the worldwide sales of BMW’s GS range of bikes.

“In an ideal world we would have loved to have supported them, but at the time we decided against it,” a KTM spokesman understated.

Bimota Vdue 500

Fuel-injected utter bloody disaster

In 1997 Bimota launched its Vdue 500, a two-stroke race replica that was heralded as being the closest thing to a GP bike on the road. Limited to only 300 bikes, it was super-exclusive. It also didn’t run. With a powerband narrower than a gnat’s c*ck due to a terrible fuel-injection system, horrific reliability and a price tag of over £14,500, it was a complete and utter disaster.

Bimota was forced to recall every single one of them and offer owners replacement SB6R machines. Not all of them took the offer up, and most opted for cash back. “It was the worst bike I’ve ever ridden, totally unrideable,” reckons motorcycle journalist Chris Moss.

The Vdue was meant to be Bimota’s saviour but its total failure plunged the firm into financial crisis and the company went bust (again) in 1999. At which point collectors turned up at the factory’s gates in white vans and snapped up the remaining Vdue’s at bargain prices. Some were converted to carbs, and still ran like shit, while others currently sit in humidity controlled glass cabinets as very beautiful, but completely useless Italian ornaments.

Now Bimota keeps things more simple, using tried and tested engines like the BMW S1000RR's.

Triumph TT600

The Jerk

Triumph’s 2000 TT600 was meant to be Britain’s answer to the supersport class. A 600cc race rep that could take on the CBR, R6, GSX-R600 and ZX-6R. Okay, Triumph missed the mark when it came to styling. With its twin rocket launcher air intakes and jelly-mould fairing it looked like an ancient CBR, but surely it would ride well? Unfortunately Triumph launched the bike without actually getting around to sorting the fuel-injection map. It was, quite simply, terrible. The throttle response was a light switch and drove riders to distraction. The subsequent panning reviews put a huge damper on what wasn’t actually that bad a bike. Well, once Triumph got the injection right a few years later, anyway.

Ducati 999

Hello ugly

Ducati unveiled its long-awaited and much anticipated replacement to Massimo Tamburini’s legendary 916 design in late 2002. And the world stood still. Then the world drew in a breath, paused for thought and formed a collective impression that this was indeed a very ugly bike.

Despite being a better motorcycle to ride, Pierre Terblanche’s concept was panned the world over for its physical appearance. Sales were slow despite WSB success (in the UK the last 916-style bikes actually out-sold the 999 in 2003) and even a few tweaks to try to improve its look failed to help.

The 999 was replaced in 2007 by the 1098, which looks an awful lot like an updated 916, something the 999 should always have been. Unsurprisingly the 1098 has proved a tremendous hit, breaking Ducati’s sales targets and helping the company climb out of the hole the 999 helped put it in.

“Some people had a negative reaction to the styling, not everybody did,” said Terblanche in 2010. “Maybe it was a bit early, too futuristic, who knows? When you do projects like this you obviously intend that that they will be liked by everybody, but that doesn’t always happen.”

Evidently not.

Suzuki TL1000S

The Great Rotary Damper Fiasco

Suzuki’s TL1000S was launched in 1997 with a revolutionary rotary rear damping system. The idea was that by separating the spring and the damping, the units could be made shorter so the bike’s wheelbase could be kept down.

Although inexplicably fine at the world launch in Atlanta, once production units came to the UK it became very apparent that it didn’t work. The system rapidly over-heated, under-damped and lead to huge handling problems.

Following claims of tank-slappers and series accidents, Suzuki freaked out and were forced to do a worldwide recall and retrospectively fit a steering damper.

“The TL was completely developed in Japan and the first time we rode it in the UK we were like, ‘oh shit’,” a Suzuki source said some years ago.

Perversely, the 'widow-maker' reputation gave the TL a cult popularity.

Nevertheless, the following year the TL1000R was launched complete with a steering damper.

It also felt overweight, with lazy (and stable) geometry, probably a knee-jerk reaction to the bad press.

The rotary damper eventually died six years later, along with the TLs, which is a shame because there isn’t actually anything wrong with rotary dampers.

National Motorcycle Museum

A Fag Too Far

On September 16 2003, someone (and we really tried to find his name) nipped outside the National Motorcycle Museum in Birmingham for a crafty fag. Unfortunately the same person didn’t check they put it out and tossed the still burning butt into a pile of old air-conditioning filters. The resulting fire swept through the building, burning over 500 bikes, half of the total collection, and causing over £20million of damage.

Many of the bikes damaged were one-offs, some reduced to frames in the blaze. The Museum has since installed a sprinkler system.

Norton, Triumph etc

The British Bike Industry

When it comes to blunders, few have done it better than the British bike industry as a whole.

Sticking their collective heads in the sand and ignoring competition from Japan, failing to develop their models, sitting on their laurels and just expecting customer loyalty; and the bikes were sh*t, largely still built using pre-war tooling and often engines that were pre-war designs.

The Norton Commando summed it all up. Originally designed as a 500, the engine was bored out to 650 then 750 and finally 850, at which point is was so over-stressed and vibrated itself to bits.

Journalist Roger Willis remembers visiting the Triumph Meriden factory in 1981 just before it finally closed, signalling the end of the British bike industry. “At the end of the production line there was an old man whose job it was to stand on the finished bike’s silencers to bend them into line. Build quality was that bad,” he said.

Although there are many culprits for the collapse of the industry, a big finger of accusation has always been pointed at Lord and Lady Docker.

Sir Bernard Docker was the MD of BSA in the 1950s who, along with his wife Norah, spent much of BSA’s profits on gold-plated Daimlers (upholstered in mink, zebra and leopard skin), and yachts.

Throughout the 1950s the pair squandered most of BSA’s vast profits and didn’t re-invest a single penny before eventually, in 1956, Sir Bernard lost his chairmanship of the company.

A few years later their lifestyle caught up with them and the pair were living as tax exiles in Jersey, whose inhabitants the ever-tactful Lady Docker referred to as “the most frightfully boring, dreadful people that have ever been born.” There is no record of what Jersey thought of her.

Yamaha YZF-R6

Erm, must be in the roundings

Yamaha launched the 2006 R6 with a new marketing ploy. Rather than boast power figures, the blurb harped on about a stratospheric 17,500rpm rev limit.

Which was all very well and good until owners actually put the bike on a dyno and discovered the rev gauge was somewhat optimistic, by about 1,500rpm.

Turns out the new R6 only revved to 16,000rpm. In America, Yamaha were forced by lawyers to send letters out to owners offering to buy back the bikes if they were dissatisfied with them.“We decided we’d better do the right thing, step up and put our money where our mouth was,” offered a Yamaha US spokesman.

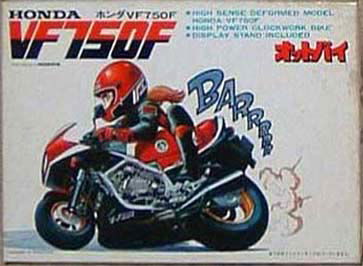

Honda VF750F

Chocolate cams anyone?

In the 1980s, one bike single-handedly destroyed Honda’s reputation for reliability. Take a bow the legendary VF750F.

Honda’s sports-tourer was hampered by top-end problems. The surface of the cam was too soft and regularly pitted, causing the cam to wear unevenly and wobble in the bearings.

As well as making the engine rattle like hell, this destroyed cam chains and cam chain tensioners, leading to rebuilds.

This bike coined the phrase ‘chocolate cams’ and made it commonplace in any owner’s vocabulary.

To silence critics Honda brought out the legendary VFR in 1986 which was a big loss leader. Honda took a hit to restore their battered reputation for reliability and completely over-engineered the VFR to make it absolutely bullet-proof.

Which it still is to this day.

Norton Nemesis

The Norton Nemesis

Heralded as Britain’s new superbike, the Norton Nemesis was designed by British designer Al Melling and presented to the UK’s press at the Dorchester hotel in 2000.

The figures were ridiculous: a 1479cc V8 motor with 235bhp, a top speed of 225mph, push-button gearshift, rim-mounted brakes and a partridge in a pear tree.

Surprisingly enough it didn’t set the world alight with interest. Most people not involved in the project regarded the whole thing as a joke, totally impossible to put into production and about as likely to ever appear as Lord Lucan riding Shergar.

A legal situation developed involving the use of the Norton brand and the project was rebranded with the name Melling.

Today Melling has a website here. We couldn't see any mention of the Nemesis on there.

- A version of this article was first published on November 17, 2010.