The Hard Road: The Real Road Racers

Road racing’s superstars may dominate the headlines, but the unsung majority are still the sport’s lifeblood. Warren Pole unpicks the fabric of ‘real’ road racing

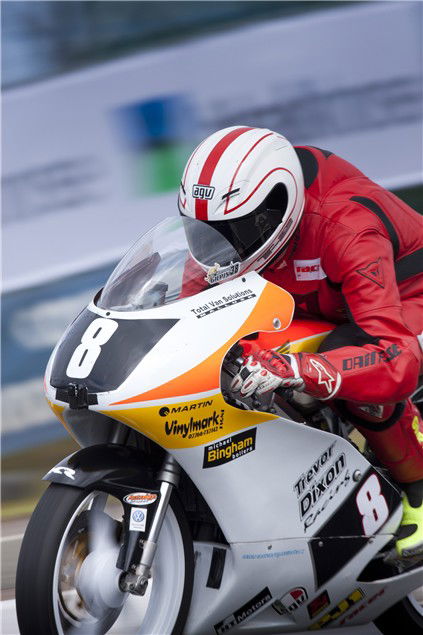

Walk through the gap in the hedge however and you’ll find yourself in another race paddock. There are no motorhomes here – caravans are as posh as it gets, while just as many are sleeping in their vans – and the team awnings coated in sponsor’s logos have been swapped for old tents while the ‘hospitality areas’ are a packet of biscuits in the toolkit and a couple of well worn mugs wearing as much grease as they are tea stains.

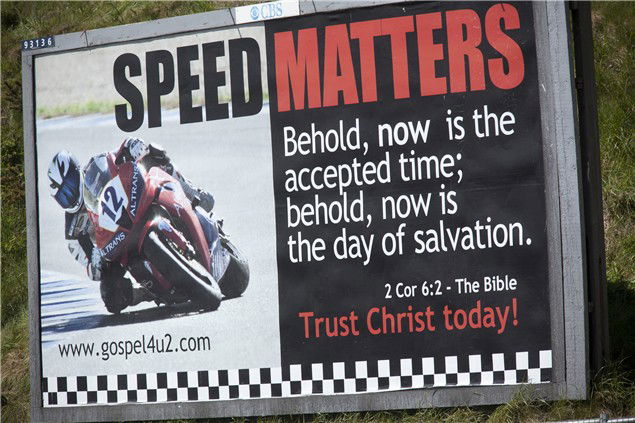

If road racing is a religion in Ireland then this paddock is the congregation. Some days they make the podium and other days they’re lucky to finish, but they’re here for the love of the sport above everything else and are running on budgets tight enough to make many trackday riders wince.

“My Honda RS125’s 14-years-old and I don’t even own it,” Darren Gilpin tells me from beneath the small awning at the side of his aged caravan. The 34-year-old 125 rider from County

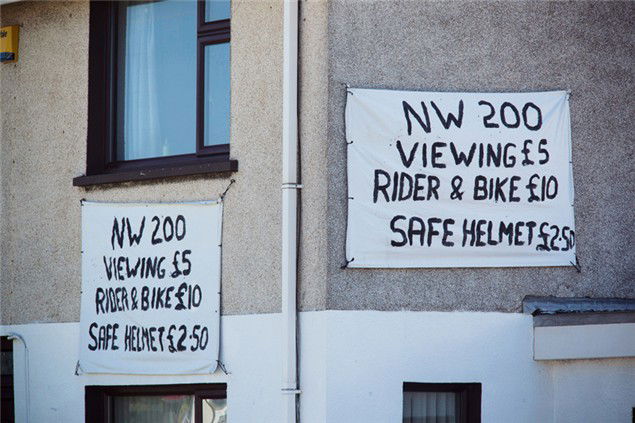

Behind the giant race trucks, awnings and uniformed mechanics of the factory riders at the North West 200 lies a second, smaller paddock. It’s easy to miss – at first glance the gap in the hedge leading into it looks like an exit into an unused field, especially as the paddock tarmac ends abruptly at its border. The illusion of there being nothing through there is compounded by the lie of the land, which slopes up to the hedge, and then down beyond it, meaning that from within the main paddock the only way of seeing over the hedge is by climbing on top of one of the more deluxe factory race trucks. Ironically for a road race which sees riders top 200mph on a course where kerbs, lamp-posts and houses all lie inches from the racing line, you can’t do this. Health and safety you see.

Antrim is typical of the Irish road race breed, pouring everything he has into his racing. “I’ve never been on holiday abroad because all my holidays are spent at race weekends and my house doesn’t even have curtains – any spare money I do have goes into running the bike. I wouldn’t complain about any of it though because I love road racing, it’s such an addictive sport.”

His family must love it too – even Gilpin’s wedding four years ago was planned around it. “We got married a week before the Northwest and came here racing for our honeymoon. My wife Roisin’s a very understanding woman.”

This year’s North West 200 was held on the same weekend as this year’s Monaco F1 Grand Prix and the contrast between the two couldn’t be more extreme. Both are on closed roads and both are by the sea but there the similarities end.

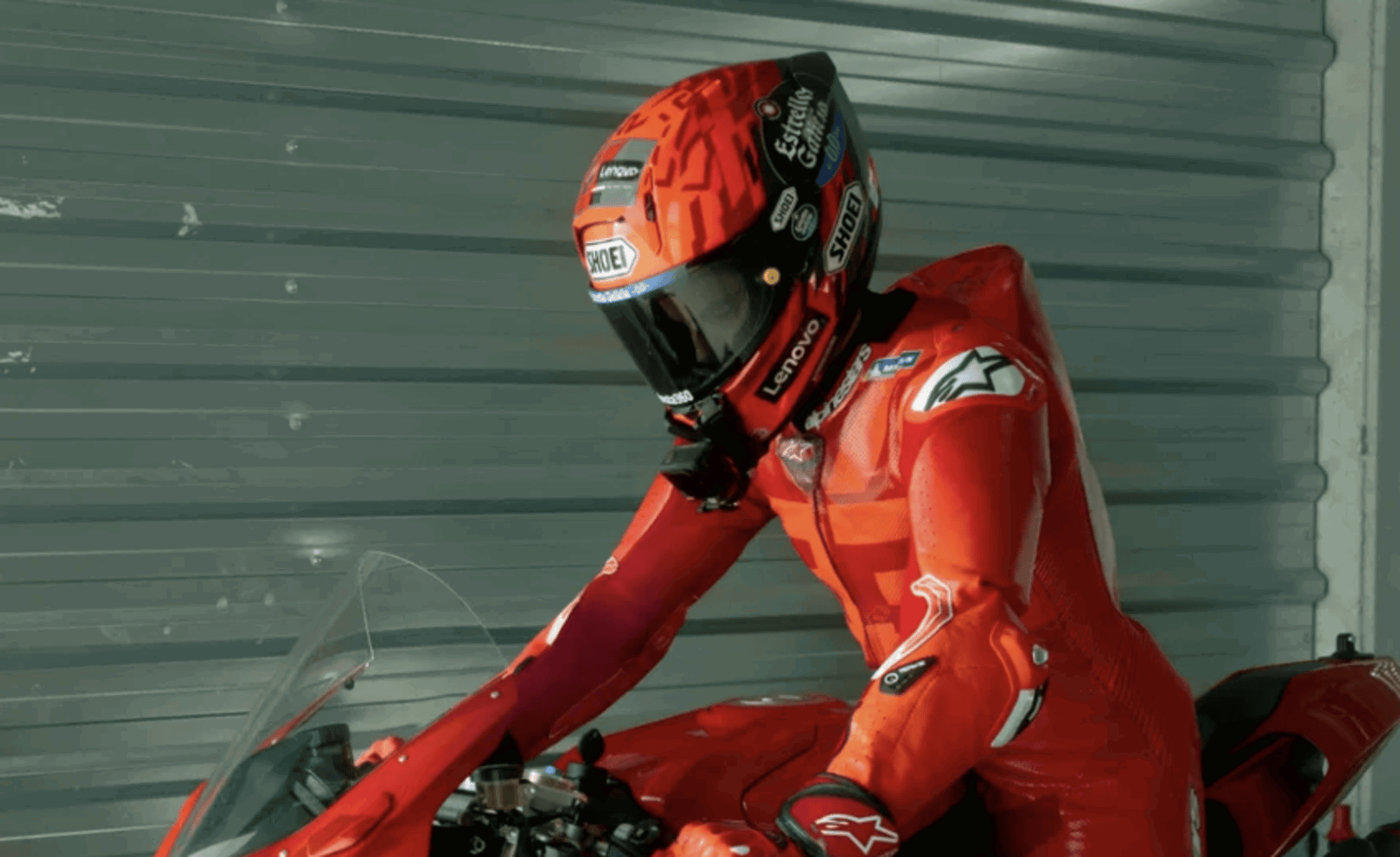

While Monaco is a shiny jewel of a spectacle accessible only to the richest and most famous members of Europe’s billionaire elite with racing that’s little more than a pricey procession, the North West is a true dogfight among riders prepared to lay it all on the line for very little. Beyond the front row of the grid in any class it’s unlikely many, if any, are being paid to be there.

Legends like Phil McCallen, Joey Dunlop, Carl Fogarty and Steve Hislop have all won at the North West, while others including the circuit’s most successful rider ever, Robert Dunlop, have lost their lives there. Dunlop was killed after a fall in practice for the 2008 250cc race and his son Michael went on to win the same race two days later, dedicating the win to his father. Grown men cried in the grandstands that day. It was an outstanding display of the bravery, courage and sportsmanship on display in road racing.

Paul Robinson, another rider making racing ends meet from one weekend to the next, felt Dunlop’s death more keenly than most. His father Mervyn, a road racing great in his own right, was brother-in-law to the Dunlops and the man who introduced both Joey and Robert to the sport.

Tragically, Mervyn was killed racing at the North West in 1980, but Paul continued going to the races with the Dunlops before starting racing himself in 1993. Since then he has seen the sport take not only his father, but both Joey and Robert. These profound losses have never stopped him racing but he admits he may never get over them.

“I don’t really think I’ve come to terms with it, with all three of them. Not only that, lots of close friends have been killed racing as well. But you always have the mentality of ‘well, it won’t happen to me, I’ll be lucky’. You have to think that – you wouldn’t be able to do this otherwise.”