Burt Munro's Speed Obsession

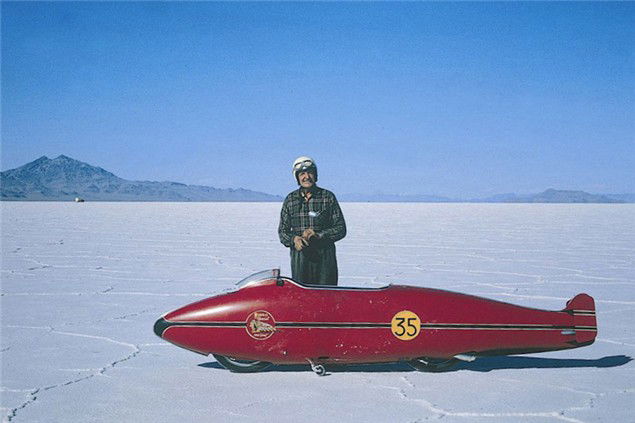

From a small shed in a small town in a small country at the very bottom of the world came an old man and an old bike - to capture the most remarkable world speed record ever

Everybody who's ever owned a bike has wanted to know how fast it goes. It's human nature. Trouble is, once you'veridden your bike flat out, you just know you're going to want to go even faster. That's human nature too. But while most of us are content to buy a few aftermarket parts to increase the bhp, some people feel the need to take things further. And in Burt Munro's case, much, much further.

In 1920, Munro bought a 50mph Indian Scout. He spent the next 46 years modifying it in his shed, then the 63-year-old grandfather took the vintage machine to the Bonneville Salt Flats and clocked 212mph. The equivalent today would be taking a Suzuki GSX-R1000 and modifying it - designing and building all the parts yourself, on a shoestring budget - and hitting 680mph!

Most people now know of Burt Munro through the movie The World's Fastest Indian, starring Sir Anthony Hopkins as Burt Munro. But what was the real Munro like? What possessed him to live and sleep in a shed for a quarter of a century so he could achieve that one perfect run through the Bonneville timing lights? We tracked down Munro's son, John, in New Zealand, to find out what his father was really like and why he dedicated his life to making offerings to the God of Speed. The pictures published here are from the Munro family's private collection and most have never been seen before.

Herbert J. 'Burt' Munro was born near Invercargill at the south end of New Zealand's South Island. "It was originally spelled 'Bert,'" says Munro's son, "but the Americans decided to call him Burt so he went along with it."

At 15 years old, Munro bought his first bike. In 1917, at the age of 18, he paid £50 for a new Clyno with sidecar. After removing the chair, Munro raced the bike in local meets and set a few local speed records at the Fortrose circuit near Invercargill. But it wasn't until 1920 that Burt Munro encountered the machine which would change his life. It was a 1919 Indian Scout - a 600cc, side-valve V-twin with a three-speed, hand-change gearbox and a foot-operated clutch. It had no rear suspension, and only two inches of travel at the front. To this day, the bike has been referred to as a 1920 model (Burt even had this painted on the bodywork) but John Munro can now correct this universal misconception. "It was actually a 1919 model," he admits, "but Burt bought it in 1920 so he always called it a 1920 model."

The first major modifications were made in 1926. This consisted mainly of removing surplus items to reduce weight, plus some alterations to the riding position. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Munro designed and built his own four-cam system to replace the standard two-cam, push-rod set-up and converted the bike to run with overhead valves. Over the years, Munro would make his own barrels, pistons, flywheels, cams and followers, and even his own lubrication system. Impressive as all this was, it was Munro's unorthodox methods and shoestring budget which made his engineering feats so remarkable. He made barrels from pieces of cast iron gas pipe, scrounged from the gas company after they'd been dug up for replacement - Munro believed that after spending so long underground the iron would be 'well seasoned'. He hand-carved con-rods from an old tractor axle, carved the tread off normal tyres with a kitchen knife to make slicks, and one report even had him casting pistons in holes dug on the local beach! This, like so many stories surrounding Munro, is a myth, as his son reveals. "It's not true. There are so many myths about my dad. When we were filming at Bonneville people kept coming up to me and asking if all these weird stories were true. It happens here in New Zealand too."

For Burt Munro, time spent on even the most laborious jobs was time well spent. "It's almost impossible for me to give a true picture of the time I've spent on my cycles," Munro wrote in 1970. "The last 22 years have been full time. For one stretch of 10 years I put in 16 hours every day, but on Christmas Day took the afternoon off."

Wayne Alexander of Britten Motorcycles - who built two replicas of the Munro Special for the movie - is amazed at the time and effort Munro put into his project. "Burt would spend 40 hours hand-filing a piece that could have been done on a mill in 30 minutes," he says. Alexander also marvels at Munro's skill in designing and building complex working parts without technical drawings. "He was remarkable. He could hold huge images in his head."

According to Munro's son, his engineering talents were innate. "His skills were all self-taught. There's a bit of a mechanical bent in the family. One of his uncles invented some agricultural machinery which was sold around the world. I've inherited it to some degree - I've invented things and patented them."

Munro became so obsessed with his quest that he eventually split from his family to work full time on his bike. His son recalls: "Mum and dad separated in late 1945. Dad bought a plot on the other side of town and built a concrete shed where he worked on his bikes, slept and lived."